Predictably Irrational 1 – Relativity, Supply, Demand and Free

Today’s post is our first visit to the book Predictably Irrational by Dan Ariely.

Dan Ariely

Dan is Professor of Behavioral Economics at Duke University.

I first came across Dan back in 2012 when I retired from earning a living and began to take MOOCs (massive open online courses for recreation).

- Social psychology was one of my favourite topics.

I have a degree in Psychology and I like the way that understanding human behaviour and bias feeds into investment.

- Dan is one of the leading lights in this area, and Predictably Irrational is his first book on the topic (of three so far).

Pain

Dan begins his book by explaining how he developed an interest in irrationality.

- When he was 18 years old, he was badly burned (70% coverage of third-degree burns) by a magnesium flare.

He spent three years in hospital and then had to wear a mask and what he calls a “Spider-Man suit”.

- This made him an outsider and he started to observe human behaviour and to wonder about it.

Every day he had bandages removed and ointment applied – a very painful process.

- He noticed that the nurses had theories about the pain which fed into their approach to removing the bandages (fast vs slow, where to start and end).

These theories had no scientific basis, and Dan did not agree with them, but he was unable to influence the nurses.

When he went to university, he began experiments into the nature of pain.

- After a few years he had evidence to support his theory that the nurses – though vastly experienced, and kind – were wrong (biased).

I told the nurses and physicians, that people feel less pain if treatments are carried out with lower intensity and longer duration than if the same goal is achieved through high intensity and a shorter duration.

Though the nurses felt that their own feelings (on the extended screaming of their patients) should be taken into account, they changed their approach (at least in the hospital Dan attended).

- I decided to expand my scope of research, from pain to the examination of cases in which individuals make repeated mistakes – without being able to learn much from their experiences.

Behavioural economics

Dan studies behavioural economics.

- Economics is generally based around the idea that people are rational, but in practice, they are not.

Most of us feel that we are rational ourselves, but others are less so.

- Dan’s point – as evidenced by the title of his book, is that we are predictably irrational:

Our irrationality happens the same way, again and again.

Relativity

Chapter one explains that everything is relative – even when it shouldn’t be.

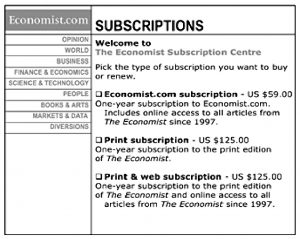

Dan begins with Economist subscription offers.

The first offer – the Internet subscription for $59 – seemed reasonable. The second option -the $125 print subscription – seemed a bit expensive.

But the third option offers both of the others for the price of the second.

- This is designed to present option 3 as a bargain.

I may not have known whether the Internet-only subscription at $59 was a better deal than the print-only option at $125. But I certainly knew that the print-and-Internet option for $125 was better than the print-only option at $125.

The second option is a decoy.

- When Dan removed Option 2, many more people chose option 1 than option 3.

Most people don’t know what they want unless they see it in context. Given three choices, most people will take the middle choice.

This is how most items (say TVs – but not the Economist) are presented.

High-priced entrées on the menu boost revenue for the restaurant–even if no one buys them. Because even though people generally won’t buy the most expensive dish on the menu, they will order the second most expensive dish.

And the second most expensive will usually have a better profit margin.

- The same technique (a pricier option than no-one will buy) was used by manufacturers of bread making machines to establish that $275 was a good value price for such a machine.

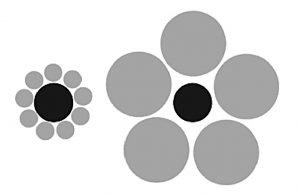

Here’s the same trick in visual form.

- The black circle on the left looks bigger, because you are judging it relative to the smaller grey circles.

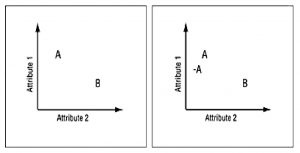

We also tend to focus on comparing things that are easily comparable–and avoid comparing things that cannot be compared easily.

When a salesman wants to force your choice of an option, he will make it easily comparable to an obviously inferior option.

- This is the trick used by The Economist.

The “odd one out” on the list will be ignored completely.

- This is the decoy effect.

Dan demonstrated it using doctored photos of students previously chosen as attractive.

- Whoever’s doctored photo was used as a (less attractive) decoy would be chosen as most attractive.

Women on dating sites often use a similar technique (or so I am told).

- They pose with a group of friends, some of whom are noticably less attractive than they are.

And people do the same in bars, with slightly less attractive “wing-men” (or wing-women).

- It works for conversational skills as well as appearance.

Relativity also makes people miserable, when they compare their salary, wealth, car or home with those of their friends.

- It’s not a good idea to try to Keep Up With The Joneses.

Dan notes that publishing executive pay had the opposite effect to that intended.

- Competition between executives increased, and so did their pay-packets.

In 1976, the CEO/worker pay ratio was 36.

- By 1993 it was 131, and the law forcing publication of executive pay was passed.

When the book was written (around 15 years later) the ratio was 369.

As an investment-firm exec told Dan:

If everyone knew everyone else’s salary, all but the highest-paid individual would feel underpaid.

Since money (beyond a certain point) doesn’t make people happier, it must be envy that drives us all to make more of it.

- Dan quotes HL Mencken’s statement that it is your brother-in-law’s salary that counts, since your wife will make sure that you know about it.

The best defence against this inflation is to ignore options (houses, cars) you can’t afford.

The more we have, the more we want. And the only cure is to break the cycle of relativity.

And look at the big picture – try to think in absolute terms (£s) rather than in percentages.

- In the example Dan uses, $7 is $7, whether you save in on a $25 pen or on a $400 suit.

If you will spend £3K on leather seats in a car, you should be more than happy to spend that amount on a new sofa.

Supply and demand

Dan starts chapter 2 with the story of how a market for black (actually, grey) pearls was created.

- Salvador Assael put a string of them in the window of Harry Winston the jeweller, at a very high price – and he took out full-page ads in the glossy magazines.

As Mark Twain said:

In order to make a man covet a thing, it is only necessary to make the thing difficult to attain.

Dan says that like birds, human imprint on the first price they see for an item (this is known as anchoring).

- Assael anchored the price for his new pearls to the finest gems already in existence.

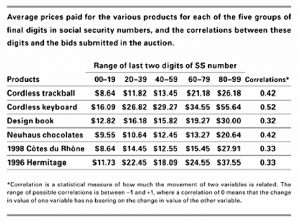

Dan demonstrates anchoring even to arbitrary numbers (such as the last two digits of a person’s social security (national insurance) number.

- His study had participants bid for items having initially priced them against these digits.

The students with the highest-ending social security digits (from 80 to 99) bid highest, while those with the lowest-ending numbers (1 to 20) bid lowest.

And:

Relative prices seemed incredibly logical. Once the participants were willing to pay a certain price for one product, their willingness to pay for other items in the same product category was judged relative to that first price (the anchor).

Price tags by themselves are not necessarily anchors. They become anchors when we contemplate buying a product or service at that particular price.

People who move to a new city generally remain anchored to the prices they paid for housing in their former city. People spend an amount similar to what they were used to, even if this means having to squeeze themselves and their families into smaller or less comfortable homes.

Transplants from more expensive cities [also] sink the same dollars into their new housing situation as they did in the past.

Dan tested whether anchors can be moved by paying subjects to listen to annoying sounds.

Those who first faced the hypothetical decision about whether to listen to the sound for 10 cents needed much less money to be willing to listen to this sound again (33 cents on average) relative to those who first faced the hypothetical decision about whether to listen to the sound for 90 cents.

This second group demanded more than twice the compensation (73 cents on average).

In the second phase members of the 10-cent and 90-cent groups were offered a new annoying sound for 50 cents.

The 10-cents group offered much lower bids than the 90-cents group.

They stuck to their first anchor – they already knew how much they wanted to listen to an annoying sound.

- The same result was found when a third-round introduced yet another anchor price (and another annoying sound).

First impressions are important, whether they involve remembering that our first DVD player cost much more than such players cost today (and realizing that, in comparison, the current prices are a steal) or remembering that gas was once a dollar a gallon, which makes every trip to the gas station a painful experience.

We also assume that things are good or bad on the basis of other people’s behaviour (now called social proof).

- The phenomenon itself is called herding (for example, preferring popular – and crowded – restaurants.

We also self-herd, by forming habits (such as the expensive morning takeout coffee).

- And those habits are likely to become more complicated and more expensive (bigger and priceier coffee options).

You don’t think about trade-offs anymore. You’ve already made this decision many times in the past, so you now assume that this is the way you want to spend your money.

Dan explains that Howard Schultz positioned Starbucks as a “continental” coffeehouse so that he could charge more.

- I’m not sure how this applies to Europe, where they seem very American indeed (disclosure – I’ve never been to a Starbucks alone).

The logic was to avoid people anchoring to cheaper coffee at US shops (eg. Dunkin Donuts – I shop I have never visited at all).

Dan’s next experiment looked at framing.

I told the students that I would be conducting three readings from Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass that Friday evening: one short, one medium, and one long. Owing to limited space, I told them, I had decided to hold an auction to determine who could attend.

First, we need an anchor:

I asked half the students to write down whether, hypothetically, they would be willing to pay me $10 for a 10-minute poetry recitation. I asked the other half to write down whether, hypothetically, they would be willing to listen to me recite poetry for ten minutes if I paid them $10.

The first group offered a dollar for a short reading, two for a medium and three for a long.

- The second group wanted payment: $1.30, $2.70 or $4.80.

I was able to take an ambiguous experience and arbitrarily make it into a pleasurable or painful experience.

And the response to the short reading drove the prices for the longer ones. Mark Twain again:

Work consists of whatever a body is obliged to do, and play consists of whatever a body is not obliged to do.

My thoughts exactly.

Could it be that the lives we have so carefully crafted are largely just a product of arbitrary coherence? We made arbitrary decisions at some point in the past and have built our lives on them ever since, assuming that the original decisions were wise.

We should pay particular attention to the first decision we make in what is going to be a long stream of decisions (about clothing, food, etc.).

This is a form of lifetime cost accounting.

- We should also pay particular attention to large yet discretionary budget items (in my case, pre-Covid restaurant meals).

For Dan, these experiments negate the theory of supply and demand as a price-setting mechanism.

- Since people can be manipulated into paying different amounts, demand is fluid.

- And anchoring to (supply-side) prices means that demand is not independent of supply.

The relationships we see in the marketplace between demand and supply (for example, buying more yoghurt when it is discounted) are based not on preferences but on memory.

The sensitivity we show to price changes might, in fact, be largely a result of our memory for the prices we have paid in the past and our desire for coherence with our past decisions – not at all a reflection of our true preferences or our level of demand.

I am not suggesting that doubling the price of gasoline would have no effect on consumers’ demand. But I do believe that in the long term, it would have a much smaller influence on demand than would be assumed from just observing the short-term market reactions to price increases.

This also has implications for free markets.

The choices and trades we make are not necessarily an accurate reflection of the real pleasure or utility we derive from those products. [So] It is not clear that the opportunity to trade is necessarily going to make us better off.

Dan uses this as an excuse to argue for greater government control of “essentials such as health care, medicine, water, electricity, education”.

But of course, that would require the government to outperform the market at an aggregate (rather than an individual) level.

- And all the evidence is in the opposite direction.

Zero cost

Chapter 3 shows that sometimes, even paying nothing is paying too much.

Getting something free feels very good. Zero is an emotional hot button – a source of irrational excitement.

Have you ever gathered up free pencils, key chains, and notepads at a conference, even though you’d have to carry them home and would only throw most of them away? Or have you bought two of a product that you wouldn’t have chosen in the first place, just to get the third one for free?

Dan’s experiment involved expensive and cheap chocolates from Lindt and Hershey.

- When the Hershey Kiss became free (rather than costing one cent) 69% of “customers” chose it (up from 27%) – despite the Lindt truffle also being reduced in cost by once cent.

Getting FREE! items can make perfect sense. The critical issue arises when FREE! becomes a struggle between a free item and another item – a struggle in which the presence of FREE! leads us to make a bad decision.

You gave up a better deal and settled for something that was not what you wanted, just because you were lured by the FREE! Most transactions have an upside and a downside, but when something is FREE! we forget the downside.

This is down to loss aversion – choosing the non-free item opens us up to a loss.

A follow-up experiment allowed trick-or-treating children to exchange Hershey Kisses for heavier Snickers bars (containing more chocolate) in two sizes.

- Setting the cost of a smaller bar to zero Kisses meant that more kids chose it, even though it was a worse deal.

A third experiment showed that people preferred a free $10 Amazon gift certificate to a $20 gift certificate for $7.

- Zero also works with food (“zero calories” or “fat-free”).

Dan cautions us to include time in our calculations.

If we spend 45 minutes in a line waiting for our turn to get a FREE! taste of ice cream, or if we spend half an hour filling out a long form for a tiny rebate, there is something else that we are not doing with our time.

I find this to be increasingly the case as I get older.

- I’m no longer willing to attend free investment conferences unless I expect to receive actionable information.

Of course, free conferences are the least likely ones to provide this.

Conclusions

That’s it for today.

- We’re off to a good start and have covered around a quarter of the book.

So we’ll have three more articles on this topic, and then a summary.

- Until next time.