Weekly Roundup, 5th September 2022

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup with inflation.

Structural inflation

Buttonwood looked at what investors should do if inflation is structural.

When economic growth drives asset prices, stocks and bonds diverge. When inflation drives them, stocks and bonds often move in tandem. For as long as central bankers kept a lid on inflation, investors were protected.

Before the 21st century, stocks and bonds had a mostly positive correlation.

So the argument about inflation has moved on from “transitory vs persistent” to cyclical vs structural”.

Those in the “structural” camp argue that the recent period of low inflation was an accident of history—helped by relatively calm energy markets, globalisation and Chinese demographics, which pushed down goods prices by lowering the cost of labour.

That’s all gone now.

- If you expect recurrent energy price spikes and deglobalisation, you should adjust your portfolio away from 60/40.

Long-short equity strategies and commodities are the suggestions, but I think, that trend-following should also be on the list.

Unemployment

The Economist looked at whether unemployment has to go up in order for inflation to go down.

The inflation problem remains unresolved as long as rapid growth in workers’ wages continues to power a spending boom. A drop in the price of any one thing, such as oil, only leaves more room for spending on another.

The Fed needs to weaken workers’ bargaining positions by introducing a bit of slack into the labour market.

That means too many people chasing too few jobs, which leads to lower wages.

- But in the three months to July, wage inflation was running at 7% pa.

The ratio of job openings to those unemployed is near a record high, but some argue that this presents an opportunity:

The relationship between vacancies and unemployment may at current levels be a very steep one, such that tapping the monetary brakes yields a little extra unemployment but a big drop in openings.

Not all economists are convinced:

Alex Domash and Larry Summers noted that there has never before been a large drop in the number of job openings that has not coincided with a meaningful rise in unemployment.

But with vacancies in uncharted territory, the old rules might not apply.

Alternative fixes include people working more hours, and more people entering the workforce, each of which shows room for improvement.

A lot hangs on whether those who left the workforce during the worst of the pandemic decide to return. Research published last year finds that participation tends to keep rising several months after the unemployment rate hits a bottom, which it is yet to do.

So there’s a chance, although high wage inflation has not tempted anyone back in recent months (participation is still falling).

- The most likely development is that the Fed will push unemployment up.

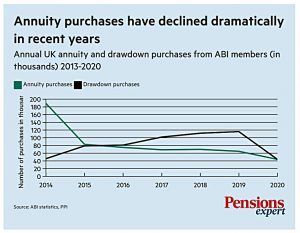

Annuities

In Pensions Expert, Stephanie Hawthorne asked whether savers might be ready to go back to annuities.

- Low interest rates made them uncompetitive and pension freedoms all but killed them off.

The annuity market saw sales plummeting from 466,000 a year in 2009 to fewer than 50,000 by 2020.

But perhaps rising rates will lead to a revival:

[Recent] data showed a slight uptick, increasing to 31,689 between October 2020 and March 2021 from 28,694 between April and September 2020.

Stephanie quotes current annuity yields of 6.2%, but these are not index-linked, so less than useless with today’s inflation.

- Index-linked yields are less than half of that.

As well as being expensive, annuities are also confusing:

People have to decide which of the following they want:

One option would be for the government to offer annuities, perhaps through NS&I. Kyalo Burt-Fulcher, an actuary at the Fabian Society says:

There would be no need for highly cautious life expectancy assumptions, or a low-risk, low-return investment strategy. This would allow annuities to be offered at materially higher rates than can ever be justified by private providers.

Such a policy could benefit more than just pensioners. The state annuity provider could be expected to run at a profit for the taxpayer. Moreover, it would produce the ready pool of assets that could be deployed into UK infrastructure [and] green projects.

That sounds like an idea worth exploring, though the insurance companies which dominate the market would lobby against it.

I update annuity values each month as part of my overall portfolio valuation, and to me, they still look crazy expensive.

- Last month, the yield I could obtain for an index-linked annuity was 2.96%.

That gives a payback period of 34 years, which means I would get my initial capital back at age 96.

- And I would have thrown away 34 years of portfolio growth.

Things improve slightly if you delay taking an annuity, but even at age 70 (and ignoring the growth you have thrown away), the break-even age is around 94.

CDC pensions

In the FT, David Pitt-Watson of the Royal Society for Arts argued in favour of CDC pensions.

- He says that they could boost retirement income by 30%.

He starts with the purpose of a pension:

Most pension savers will say it is an income which lasts them from the time they retire until the time they die. So the central question in a pension system is how to find the most effective way to provide a lifetime income.

By this definition, DC pots are tax-advantaged savings rather than pensions.

- Converting them to a pension means buying an annuity, and these are expensive (see above).

An annuity typically invests in very safe, very low-interest bonds, the insurer has to set aside reserves in case its calculations are wrong (it needs to make a profit) and so the saver gets a poor pension, which often has no protection against inflation.

So the 30% uplift comes from comparing an average return (say 3% pa real) with the poor return from annuities.

- This is drawdown and the only problem is longevity risk.

If you don’t know how long you will live, and you need to draw down more than 3% of your pot each year, then you might run out of money at some point (although probably not for a very long time, unless your withdrawal rate is very high).

- CDC solves this problem, but at the cost of taking your capital away from you.

CDC is effectively pooled DC that can only be accessed as an annuity, albeit one whose income may vary from time to time.

- So the choice is between the freedom of drawdown (and the likelihood that you will end up much better of than you started) and a slightly better annuity.

I know which option I would pick.

On his AgeWage blog, Henry Tapper wondered whether the rules of work have hardened against CDC.

The UK private pension system is no longer about employers providing [DB] pensions. Employers have found that switching from a defined benefit to a defined contribution structure has been rather easier than many in human resources thought possible.

He puts this partly down to a staged approach – closing schemes to new hires, and then to future accruals, and then paying insurers to take them off the company’s hands.

But more importantly, people do not seem to have minded the loss of a pension promise and seem to have been content with (financially at least) a much inferior promise of a pension pot. People value their personal freedom rather more than being told by their employer how they are going to be paid in retirement .

I obviously don’t agree that DC is inferior to DB – it depends on the level of DB you have (including the state pension) and on the transfer value that you are offered.

- Low interest rates in recent years have produced very high transfer values.

Where we do agree is that people do value the freedom to set their own drawdown rate.

Henry is an exception and thinks there are enough people like him to mean that there is a place for CDC.

I feel uncomfortable managing my own wealth, setting my drawdown rate and hoping I will live long enough to enjoy my retirement but not too long to run out of funds.

That would seem to require employers to run parallel DC and CDC schemes and to provide a mechanism for people to switch between them.

- I can’t see that happening, but Henry has another vision:

CDC is a pension that is payable from a fund that can be seeded from workplace DC pots or DB CETVs [transfer values] – or AVCs or SIPPs. There need be no employer involvement, no scheme involvement, there needs only be a CDC fund into which an individual can transfer their money.

This seems OK, though there might be some actuarial effects in a decumulation-only CDC scheme.

USA vs Europe

The Economist compared GDP numbers in America and Europe.

America[n] GDP per person is almost $70,000. The only European countries where it is higher are Luxembourg, Switzerland, Norway and Ireland, where figures are distorted by firms’ profit shifting. Incomes in Britain and France are equal to those in Mississippi ($42,000).

But to compare countries properly, we need a “deflator”.

For manufactured goods this is a straightforward calculation. For services, it is harder to work out a reasonable deflator.

And services are where most of the difference lies.

Combined spending on health care, housing and finance accounts for about half the difference in consumption between America and the biggest European economies.

This leads to a conceptual issue:

What are people paying for when they buy health care, a service or an outcome? What does being healthy even mean?

Americans pay more per treatment than Europeans, but they also have a lot more treatments. Yet life expectancy is five years lower than in Italy.

A more sophisticated measure than GDP would exclude “harms” like weapons, advertising and much of finance. The impacts of violence, car crashes and obesity would need to be subtracted.

- Work by Nobel prize-winner Simon Kuznets in this direction closes the GDP gap by two-thirds.

What remains is largely housing spending, where the cost per square metre measure flatters the US.

There are a few counter-points – the US has better cancer survival rates, and much of Europe underspends on defence because of US protection.

- And the US has higher productivity and longer working hours.

Quick Links

I have four for you this week, the first three from The Economist:

- The Economist said that the cloud computing giants are vying to protect fat profits

- And wondered whether Nvidia is underestimating the chip crunch

- And said that distressed-debt investors are preparing to pounce.

- Alpha Architect found that how You Sort Matters in Sorting Factor Portfolios.

Until net time