Weekly Roundup, 9th November 2020

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup with a look at efficient markets.

Contents

Politics and vaccines

This week in finance was dominated by the US presidential election, so this could be a slightly shorter roundup than usual.

- With the outcome disputed, I don’t have much to say about the Presidency, but probably the most significant result was the (very likely) failure of the Democrats to take the Senate.

This means that the Green New Deal – and all the associated renewable energy infrastructure spending – is unlikely to happen.

- Gridlock is usually good for stocks, though in this case, it means a lot of expected stimulus money won’t now arrive.

And of course, there’s the small matter of the Covid-19 vaccine that was announced by Pfizer this morning.

- So far, that appears to be very good for stocks also.

Efficient markets

Joachim Klement looked at how institutional investors distort efficient markets.

If investors herd – and all pile into a small number of fashionable stocks – the valuation of these stocks can deviate very far from fundamentals. The biggest flows in the stock market are created by institutional investors like pension funds, asset managers, and hedge funds.

Joachim notes that previous studies using quarterly data found no herding, but says that institutions often build positions over longer periods than that.

- A new study looks at ten quarters of institutional trades, separating stocks into deciles based on net buying.

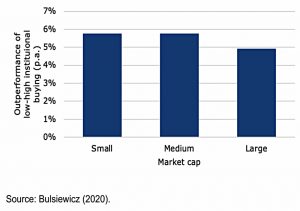

The outperformance of long/short portfolios of the top and bottom deciles was 5.8% pa for small caps (1980 to 2010) and 4.9% pa for large caps.

The outperformance was larger in the 2000s than in the 1980s, indicating that institutional investors have become somewhat more influential in the 21st century.

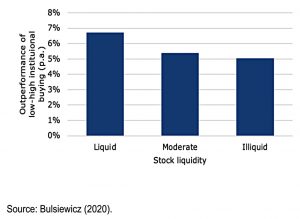

More interestingly, and counter-intuitively, more liquid stocks show greater outperformance that less liquid stocks.

- Joachim suggests that this may be simply because institutional investors avoid illiquid stocks in general, which seems somewhat plausible.

Value

In his Bloomberg newsletter, John Authers looked a couple of long-term outperformance factors.

- First up, value – stocks which are cheap (usually in comparison to their book value) will do well over time.

The only problem is – as everyone knows by now – this hasn’t worked for the last ten years.

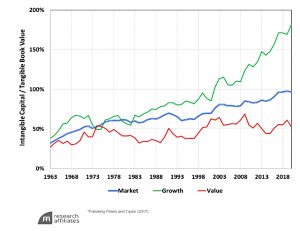

Two recent papers from Research Affiliates argue that this is because book value is no longer a good measure of the size of a firm, largely because it excludes intangibles.

- Adding back the intangibles – which have been increasing in importance over the decades – can help to fix the broken value style.

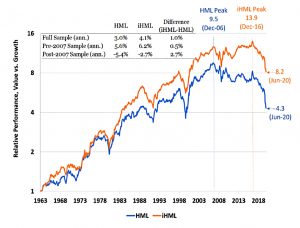

In the chart above, HML (high minus low) is the traditional value factor, and iHML is the same factor with intangibles added to book value.

- The HML outperformance peak (since 1963) is in 2006, but that for iHML is not until 2016.

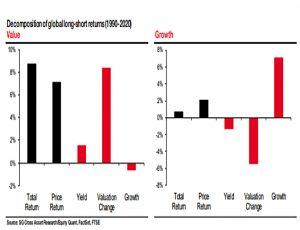

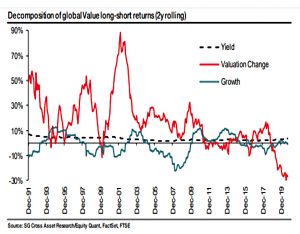

The third paper from Andrew Lapthorne at SG also looked at value.

- Returns from value come from revaluation (stocks become more expensive relative to fundamentals) but in recent years value stocks have become cheaper.

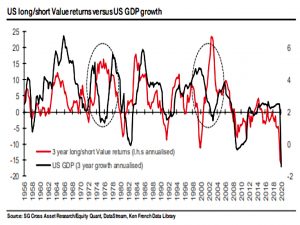

Value does badly when GDP growth is low, apart from when a stock bubble (Nifty Fifty, dot com) is bursting.

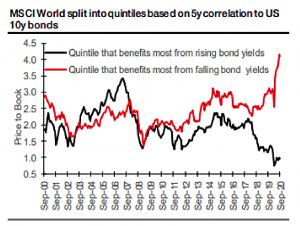

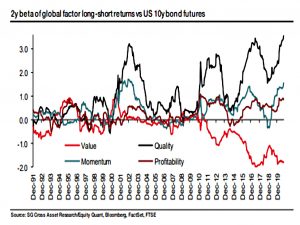

Value is also tied to bond yields – they do well when yields are rising – and this correlation has increased and yields hit record lows:

To turn this around, value is the best factor to use as a hedge against bond yields rising (which admittedly doesn’t look to likely in the near future).

So value die-hards can comfort themselves with two scenarios:

- They’ll make money if inflation returns

- They’ll win if the tech/growth bubble pops

Size

John also returned to the discussion about the size factor:

- Cliff Asness of AQR recently argued that it never existed, and appeared to work because small stocks have a higher sensitivity to the market (beta).

He said you should buy high beta stocks instead, which is interesting given the existence of the low volatility factor (which can be expected to include a lot of low beta stocks).

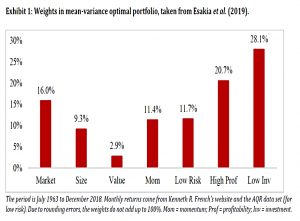

ScientificBeta have responded by saying that small companies work as diversified – they are better than value and not much worse than momentum in this regard.

Note that the best results came with high-profitability and low-investment factors, both of which reward companies for not doing things that politicians would like them to do to help the economy grow.

Dimensional said that the way to restore the size factor was to exclude stocks with low growth and profitability.

If you cut stocks that look destined to remain small, the remainder do fantastically.

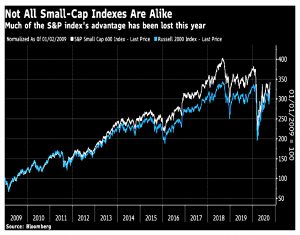

John examines this by comparing the Russell 2000 with the S&P 600, which screens out stocks which didn’t make a profit in the last year or last quarter.

- The S&P measure generally performs better but hasn’t coped well with the pandemic.

Post-pandemic GDP

The Economist looked at the impact of the pandemic on GDP figures.

- The annualised third-quarter growth figures (more accurately, rebound figures) used in the US and Japan are extraordinary, and potentially misleading.

The reported US shrinkage in 2Q20 was 31% and reported growth in 3Q20 was 33%.

- The corresponding quarterly actual movements were 9% and 7.4%, leaving the US on track for 3% shrinkage in 2020.

The IMF expects the global economy to shrink by 4.4%.

- But some of this could be caught up if the pandemic recedes.

If the economy is a hose conveying a stream of water, covid-19 is a kink constricting the torrent. The question is whether kinks today cause lingering damage to the hose, affecting its long-run capacity.

Such feedback is known as hysteresis – the dependence of the state of a system on its history.

- The IMF is worried, predicting that 2022 will be smaller than 2019 for the UK, France and Japan.

Italy won’t get back to 2019 until 2025.

So far, a lot of government stimulus has been saved, but this repair to household balance sheets could set the stage for a boom when a vaccine is found.

Failure to Launch

A couple of recent fund launches in the UK small-cap space have been pulled, most notably a small-cap version IT of the wildly successful (in both marketing and performance terms) “Buffettology” fund, run by Keith Ashworth-Lord.

- Tellworth British Recovery & Growth Trust was the other cancellation.

Which leaves Schroder British Opportunities trust as the last-man-standing in this area.

At first glance, the failure is surprising – Brexit and Covid-19 have driven UK stocks down to very cheap valuations (compared to international shares).

- We are also perceived to have a lack of sexy sectors, with the FTSE-100 weighed down by banks and energy stocks, light on healthcare and especially tech and having a distinctly international bias.

But buying into a new investment trust launch usually means losing money in the short term, as most new funds (other than those in sexy new asset classes like song royalties) soon fall to a discount to NAV.

- In the old days, this problem was solved by offering warrants that could be converted to shares once the price had recovered, but this practice seems to have fallen out of favour.

In addition, these funds could be a little early.

- The managers are no doubt thinking ahead, and want to buy before a potential recovery in 2021.

But investors are possibly still looking at rising Covid numbers and a no-deal Brexit, and might not want to buy into the recovery story until spring (which could be too late).

The third issue is the discounts on the existing UK small-cap funds, which is more than 11% (compared to the average for the last year of 6%).

- Why buy new shares with no discount when you can buy alternatives with a track record and a discount?

Quick Links

I have seven for you this week:

- The Economist reported that Ant’s IPO – the world’s biggest – has now been pulled.

- And also revisited the world of bitcoin.

- David Stevenson announced he was making a crypto bet.

- UK Value Investor sold Dunelm, which had become too expensive for his liking

- Musings on Markets had a final update on the Covid market

- Alpha Architect asked what should be the risk-free asset

- And looked at the global market portfolio’s performance from 1960 to 2017.

Until next time.