Trading For A Living #6 – Instruments and Risk Management

Today’s post is our sixth visit to Trading for a Living by Alexander Elder. Today we look at Trading Instruments and Risk Management.

Contents

Instruments

In the next chapter of his book, Elder looks at trading instruments, or as he calls them, vehicles.

He looks at six of them:

- Stocks

- ETFs

- Options

- CFDs

- Futures

- Forex

The two essential features he is looking for are liquidity and volatility.

He compares liquidity within a group.

- Liquidity is essentially average daily volume.

- A more liquid stock (say) will be easier to trade in size without slippage.

- It will usually have a smaller spread to begin with, too.

Volatility is the average short-term movement in the instrument.

- ATR is the volatility measure we have used so far in the book, but here Elder means “beta”.

Beta measures the extent of a stock’s movement (say) against the move of the market / index.

- A high beta stock will move more than the market.

- A utility stock will move less.

- A stock with a beta of 1 should track the market / index.

Elder recommends starting out with low beta instruments.

Another feature of instruments (well, markets really) is that they have a time zone.

- It’s much easier to trade within your time zone (because of sleep etc).

- It’s just about possible to trade the US from the UK.

You also need to trade instruments that allow you to go short.

- In the UK, the easiest (and most tax-efficient) way to do this is through a spread-betting account.

Stocks

See here for more on Stocks.

There are a lot of stocks (particularly in the US) and Elder recommends limiting your focus.

I have two “pools” in which I fish for trading ideas. On weekends, I run the 500 component stocks of the S&P 500 through my divergence scanner and zoom in on stocks flagged by that scan, selecting a handful that I’ll consider trading during the coming week.

Second, I review Spike picks [Spike is Elder’s website] on weekends, figuring that among a dozen top traders submitting their favorite picks, there is bound to be at least one that I’ll want to piggyback.

The number of stocks I closely monitor during the week is always in single digits.

ETFs

See here for more on ETFs.

Elder is not a fan.

The industry keeps quiet about the fact that there are two ETF markets. The primary market is reserved for “authorized participants” large broker-dealers who have agreements with the ETF distributors to buy or sell large blocks, consisting of tens of thousands of ETF shares. These middlemen buy at wholesale and then sell to you at retail.

You, as a private trader, always sit in the back of the bus in the secondary market.

They are also difficult for private investors to short.

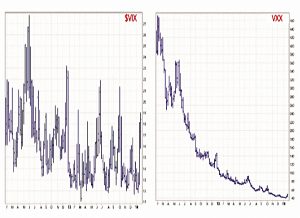

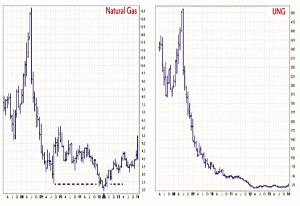

Elder particularly dislikes inverse, geared, volatility and commodity ETFs.

- He has more time for ETFs of broad stick indices.

ETFs attract many unsophisticated retail clients, but the pervasive haircuts and poor tracking of the underlying securities slant the field against them.

Options

We don’t yet have an introductory page on options.

- But options are out of our scope at this point, so I’ll leave what Elder has to say for another time.

CFDs

Contracts for difference are another form of derivative which is similar to spread betting.

- Here in the UK (unlike the US) spread-betting is not only legal but tax advantaged. (( Winnings are treated as gambling profits and not taxed – the government does this because most people lose and this way their losses cannot be set against other gains ))

As a result, CFDs are also outside our scope.

- Note that neither CFDs nor spread-betting are legal in the US.

Futures

A future is a contract for delivery of a specific quantity of a commodity by a certain date at an agreed-upon price. Futures contracts differ from options by being binding on both the buyer and the seller.

In the UK, futures trades by private investors will usually take the form of spread bets (or CFDs), so once again, futures are out of scope at this point.

Forex

The currency market is the largest asset class in the world by trading volume, with a turnover of over $4 trillion per day. While some currency trades serve the hedging needs of importers and exporters, most transactions are speculative.

Currencies trade around the clock from 20:15 GMT on Sunday to 22 GMT on Friday, stopping only on weekends. Currencies follow the sun, and small traders can’t keep up with it.

If you trade currencies, you either need to take a very long-term view and ignore daily fluctuations, or else day-trade and avoid overnight positions.

FX is driven by macroeconomic fundamentals, central bank policies (on interest rates) and news stories.

Once again, FX markets in the UK are usually accessed by private investors via spread bets, so we’ll park a deep discussion of the underlying markets for another time.

- There are also currency futures, popular with US traders.

Risk Management

The inability to manage losses is one of the worst pitfalls in trading. Beginners freeze like deer in the headlights when a deepening loss starts wiping out profits of many good trades.

It’s a general human tendency to take profits quickly but wait for losing trades to come back to even. To be a successful trader, you need to learn risk management rules and firmly implement them.

Your survival and success depend on your willingness to cut losses while they’re relatively small.

Always remember to Cut Your Losses.

Emotional traders crave certain gains and turn down profitable wagers that involve uncertainty. They go into risky gambles to postpone taking losses.

As Prof. Daniel Kahneman writes in Thinking, Fast and Slow:

Animals, including people, fight harder to prevent losses than to achieve gains.

People who face very bad options take desperate gambles, accepting a high probability of making things worse in exchange for a small hope of avoiding a large loss. Risk taking of this kind often turns manageable failures into disasters.

Except for the very poor, for whom income coincides with survival, the main motivators of money-seeking are not necessarily economic. Money is a proxy for points on a scale of self-regard and achievement.

Back to Elder:

A review of trading records usually shows that the worst damage was done by a few large losses or a long string of losses, while trying to trade one’s way out of a hole.

Probability

Each trade has either a positive expectation, also called the player’s edge, or a negative expectation, also called the house advantage, depending on who has better odds.

No system for money management can beat a negative expectation over a period of time.

Without an edge, you might as well give money to charity. Acting on hunches leads to losses.

Systems

The edge comes from systems that deliver greater profits than losses, after slippage and commissions, over a period of time.

The best trading systems are simple and robust. They have very few elements. The more complex the systems,the higher the risk that some of its components will break.

Traders love to optimize systems, making them fit past data. The trouble is, your broker won’t let you trade in the past. Markets change,and indicator parameters that would have nailed the trends last month are unlikely to nail them a month from now.

Instead of optimizing your system, try to de-optimize it. Once you develop a good system,stop messing with it.

Once you have a trading system that works, it’s time to set the rules for money management.

A pro manages his trades, accepting what’s called a “businessman’s risk” This means that the amount he risks exposes him to only a minor equity drop.

Rules and mistakes

There are two quick ways to ruin an account: not use stops and put on trades that are too large for that account’s size [over-trading].

You must use stops. You have to know your maximum level of risk – it’s as simple as that.

The two pillars of money management are the 2% and 6% Rules.

The Two Percent Rule

The 2% Rule prohibits you from risking more than 2% of your account equity on any single trade.

Measure your account equity on the first day of each month. The 2% Rule links the size of your trades to your performance as well as account size.

This rule applies only to money in your trading account. It doesn’t include your savings, equity in your house, retirement account, or Christmas club.

That seems easy enough to follow (and I do this already).

- The amount at risk is the distance from your trade to your stop (times the amount risked per unit move, or the number of units traded).

Let’s say you decide to buy a stock for $40 and put a stop at $38, just below support. This means you’ll be risking $2 per share.

Dividing your total permitted risk of $1,000 [on a $50K account] by your $2 risk per share tells you that you may trade no more than 500 shares.

Newbies with small accounts often object that this number is too low. Professionals, on the other hand, often say that 2% is too high and they try to risk less.

Elder looks at two markets, using a $50K account that may risk $1K per trade.

- We’ll look at the silver trade.

Suppose you want to buy silver at the right edge of this chart. The nearby futures contract trades at $21.415 a few minutes before the close.

You decide that if you buy, your profit target will be near $23, halfway from the EMA to the upper channel line.

Your stop will be at $20.60, the level of the latest low. You’ll be risking $0.815/oz trying to make about $1. 585/oz a 2:1 reward/risk ratio, an acceptable number.

You may buy a single mini-contract. It covers only 1,000 ounces of silver, meaning you’ll risk $815.

The Six Percent Rule

Losing traders often take on bigger positions, trying to trade their way out of a hole. A better response to a losing streak is to step aside and take time off to think.

The 6% Rule sets a limit on the maximum monthly drawdown in any account. If you reach it, you stop trading for the rest of the month.

The 6% Rule prohibits you from opening any new trades for the rest of the month when the sum of your losses for the current month and the risks in open trades reach 6% of your account equity.

If you are near the 6% limit but see a very attractive trade you wouldn’t want to miss,you have two options. You can take profits on one of your open trades to free up available risk.

Alternatively, you may tighten some of your protective stops, reducing your open risk. Just be sure that in your eagerness to trade you do not make your stops too tight.

Three open trades isn’t a lot of diversification. If you wish to make more trades, set your risk per trade at less than 2%.

If you risk only 1% of your account equity on any trade, you may open up to six positions before maxing out at the 6% limit.

The 6% Rule allows you to increase your trading size when you’re on a winning streak but makes you stop trading early in a losing streak. When markets move in your favor, you can move your stops to breakeven and have more available risk for new trades.

The 2% Rule and the 6% Rule provide guidelines for pyramiding adding to winning positions.

If you buy a stock and it climbs high enough to raise your stop above breakeven, then you may buy more of the same stock, as long as the risk on the new position is no more than 2% of your account equity and your total account risk is less than 6%.

Risk

Higher levels of risk impair our ability to perform. You need to train yourself to accept risks slowly and in well-defined steps.

Depending on how actively you trade, those steps can be measured in weeks or months, but the principle remains the same – you need to be profitable during two units of time to go up a step in your risk size.

If you lose money during one unit of time, drop down a step in your risk size.

This is especially useful for people who want to return to trading after a bad drawdown. You need to gradually work your way back into trading, without an upsurge of fear.

Managers

It used to puzzle me why institutional traders as a group performed so much better than private traders.

When successful institutional traders go out on their own, most of them lose money. When an institutional trader quits his firm, he leaves behind his manager, the person in charge of discipline and risk control.

That manager sets the maximum risk per trade. It is similar to what a private trader can do with the 2% Rule. A private trader can break the 2% Rule and nobody will know, but an institutional manager watches his traders like a hawk.

In addition to setting a risk limit per trade, a manager sets the maximum allowed monthly drawdown for each trader. Social pressure creates a serious incentive not to lose.

Private traders have no managers. The 6% Rule will save you from a series of losses.

Conclusions

The material has been lighter today, and there have been several sections that were out of our scope.

- As a result we’ve covered more ground, and the next post should see us reach the end of the book.

Today’s content was mostly stuff that majority of experienced investors will have come across before.

- But the risk management rules are very important, and have the benefit of being easy to understand and to remember.

Until next time.