Weekly Roundup, 17th January 2022

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup with a look at the London Stock Exchange.

Contents

London Stock Exchange

In the FT, Paul Marshall, the chair of the hedge fund manager Marshall Wace, said that London is becoming the Jurassic Park of stock exchanges.

The UK stock market is becoming a global backwater. It has largely failed to take part in the global rally that began in 2015. Both the US and Chinese stock markets benefit from more dynamic and expansive hinterlands, with leadership in so many of the new industries from fintech, renewables and mobility, to medtech, agritech and artificial intelligence. The US in particular is now increasingly attracting companies from all over the world.

The US has higher valuations and trading volumes, plus support from policymakers.

Marshall blames the cult of the income fund for London’s failure:

These funds are a uniquely UK phenomenon. They prioritise dividends over any other kind of return from a company and therefore by definition penalise growth. There is no comparable fund management sector anywhere in the world.

Some point the finger for the rapid growth in income funds at Hargreaves Landowne, who were growing rapidly in the 2000s (and recommending income funds) when the sector took off.

Twenty-nine per cent of UK equity investment funds are income funds.

- The Investment Association does not have a UK Growth sector.

British income fund managers believe they have a mission to protect the incomes of pensioners [which] leads them to insist on companies paying out the lion’s share of their income rather than investing it back in the business.

This is an exaggeration. In a letter replying to the article, William Wright of New Financial pointed out that pension fund equity allocations only make up 11% of the UK market.

- Some 60% is owned by non-UK investors who presumably lack the dividend fetish.

Wright offered a long list of other problems in the UK:

The disjointed structure and fragmentation of UK pensions; a supervisory framework that penalises equity, growth and long-term investment (while protecting retail investors to the point of excluding them altogether); cultural attitudes to money and wealth in the UK; the listing regime; stamp duty; and the growing differential in reporting and disclosure between private and public markets.

Personalised stock indices

The Economist looked at the rise of personalised stock indices, also known as direct indices.

Unlike off-the-shelf mutual funds or exchange-traded funds, investors in direct-indexed accounts own the underlying securities, and can tailor their portfolios to suit their needs.

Bespoke investing like this has long been available to the richest investors, but technology now means that those with “only” $100K or so can get in on the game.

- Low and zero commissions are also needed to make this approach viable, and fractional share trading also helps (particularly in the US, where lots of stocks have high prices).

There was $400M in direct-indexing accounts in June 2021, but this is forecast to reach $1.5 trn by 2025 (annual growth of close to 40%).

Direct indexing is marketed in the US on two dimensions:

- Lowering tax bills through “tax-loss harvesting” (selling losing stocks to offset gains elsewhere and reduce CGT)

- Customisation of standard indices to avoid “unethical” stocks like fossil fuels, tobacco and weapons.

Both of these could work in the UK, though CGT is not a problem for many and ESG-styled versions of the main indices are popping up everywhere.

- I would like to use it to exclude the worst companies (say 25%?) in an index, in order to have a decent shot at outperformance.

I don’t know of any direct indexing in the UK yet, but you can get close to the concept with the “pies” on Trading 212 and the self-defined portfolios on InvestEngine.

Gold

Buttonwood looked at why gold has lost some of its investment allure.

- He thinks it’s because it has been less reliable than (inflation-protected) Treasuries and it is less exciting than crypto.

Despite central bank money-printing and political tensions between the West and China and Russia, gold actually went down in 2021, its worst year in six.

Of course, it’s hard to value gold.

- Like crypto, it has no yield, and the primary demand is speculative.

Generally, the price moves in an inverse fashion to real interest rates.

There are few financial relationships that have held up as well as that between the price of gold and the yield on inflation-protected Treasuries (TIPS). The lower real, safe yields are, the greater the appeal of an asset without a yield that may rise in value.

This partly explains the lack of a move in 2021.

Despite the frenzy over inflation, ten-year real interest rates began the year at -1.06% and ended at -1.04%.

Holding the TIPS ETF has produced double the return from gold over the last decade, however.

- Regulation also means that gold is more expensive for banks to hold (since, unlike government bonds, it does not count as a “high-quality liquid asset”).

The increase in crypto’s market cap has meant that some of gold’s role as protection against fiat inflation has been stolen.

Bitcoin and ether, the two biggest cryptocurrencies, have a combined market capitalisation of around $1.3trn, ten times what it was two years ago. That is around a tenth of the perhaps $12trn of gold holdings.

Bitcoin is currently six times more volatile than gold, but when the gold standard ended in the 1970s, gold also started out as a very volatile investment asset.

- Institutional holdings of gold grew for two decades, and the same might happen with crypto.

I have been surprised by gold’ inability to react over the past couple of years and have no plans to add more precious metals to my existing holdings.

- I will be (slowly) adding to crypto, but it will take another year or so for this position to catch up with the metals.

Scarce capital

Buttonwood also wrote that capital will become more scarce in the 2020s.

Today capital is abundant. A middle-aged global workforce has lots of savings to put to work. Low long-term interest rates and expensive assets point to a scarcity of worthwhile ways to deploy those savings. New businesses are often ideas-based and do not need a lot of capital.

But demand for capital will grow for three reasons:

- Populist economics (MMT and similar)

- Shorter supply chains, and

- The transition to green energy.

Populist economics means that fiscal stimulus is popular again.

Policy constraints, such as budget deficits, bind less when interest rates are low. But over time deficit-financed spending will start to absorb excess savings.

Supply chain issues during the pandemic will mean a greater focus on business continuity.

Even modest near-shoring will require more capital. A general increase in working

capital seems likely. Companies lost sales during the pandemic for want of stock.

There will also be duplication of industries vulnerable to Chinese interference (such as semiconductors).

And the energy transition will mean lots of spending.

Any serious attempt to arrest the climb in the global temperature requires junking the assets underpinning the carbon economy—oil rigs, coal-fired power stations, petrol forecourts—and building a new infrastructure based on electric vehicles, wind and solar power and battery storage.

In the short term (during 2022) we may not see much of this tightening, and there could be even more excess capital.

- But as the decade continues, capital should become scarce.

Housing boom

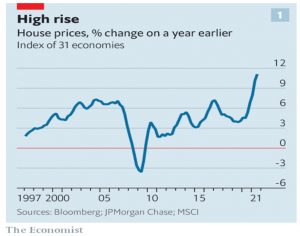

The Economist also looked at how long the global housing boom might last.

The negative case is that government stimulus is winding down, and money could be spent on hospitality and holidays now that they are both available again.

- We might also have higher interest rates in response to higher inflation.

So far this isn’t having an impact on housing, and there are three forces that could support prices:

- supply constraints

- solid household balance sheets and

- a new desire to spend more on living arrangements.

The households driving the boom are well-off, with stable hobs.

- Interest payments are historically low relative to disposable income, and the increasing popularity of fixed-rate mortgages means that interest rate hikes would have little short term effect.

The pandemic has shifted preferences towards home working, and homes that support offices.

- Bigger gardens are also more popular.

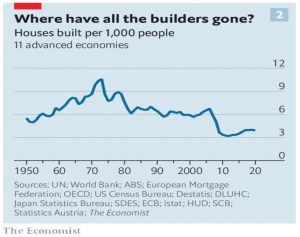

The key factor is probably supply – housebuilding is at half the level (relative to rich world populations) that it was in the 1960s.

- The pandemic hasn’t helped, either, with lockdowns and shortages of materials and labour.

Property shortages mean that demand will translate into higher prices for the foreseeable future.

Crypto

The Economist also looked at the chances of building better (greener, faster, more decentralised) blockchains.

Today’s blockchains are fiendishly complex, energy-hungry and, perhaps

counterintuitively, centralised.

Current blockchains have two key features:

One is a “consensus mechanism”, a way for users to agree on how to write new transactions in the database. The other is a set of incentives that keeps the system alive. Rewards need to draw in enough users to help maintain the blockchain. And penalties have to dissuade them from attacking it, say by mimicking lots of fake users.

Bitcoin uses new coins as the carrot, distributed to “miners”.

- The current reward is 6.25 BTC (around $250K) to the computer that solves a maths puzzle first.

This means investing in a lot of computer kit – which pushes up the cost of taking over half of the mining power of the network.

The drawbacks of this “proof of work” are:

- a lack of scalability (BTC handles just 7 transactions per second and fees are high)

- centralisation around a few big pools of miners

- massive energy use

The main alternative is “proof of stake” where the existing holders of a crypto coin make the decisions about its future.

- The stick is destroying some of your coins if you misbehave.

Proof of stake uses less energy and is faster, but still involves centralisation (around early adopters and large holders or “whales”).

- It’s also complicated to switch over, as Ethereum is discovering.

I think that capacity issues (which lead to high fees) and centralisation (which means coins are controlled by people you trust less than the government or listed corporations) and the key hurdles to the mass adoption of “pure” crypto.

- And with no good fixes on the horizon, there’s a fair chance that corporate of government blockchains will get there first.

Quick Links

I have five for you this week, the first four from The Economist:

- The newspaper said that expensive energy is baked into Britain’s future

- And that the Kazakh crisis is only one threat hanging over the uranium market

- And that more government intervention risks being counterproductive

- And wondered whether big oil’s bounce-back can last.

- UK Dividend Stocks asked why anyone would want to invest in the FTSE-100.

Until next time.