Weekly Roundup, 24th January 2022

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup with inflation.

Inflation

John Authers looked at the 7% US inflation print and concluded that inflation is durable rather than transitory.

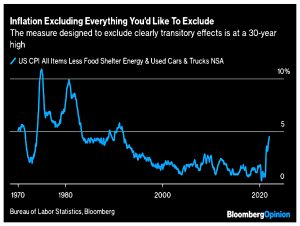

The strange “inflation without food, fuel, shelter and used vehicles” measure that was used to promote transitory inflation is now at a 30-year high.

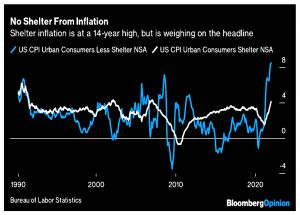

Shelter inflation is at a 14 year high.

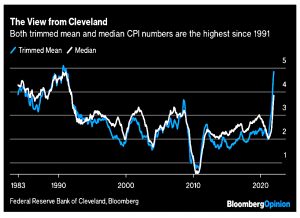

The median CPI and the “timmed mean” are at 30-year highs.

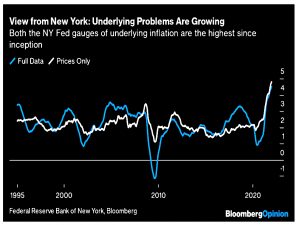

The “underlying inflation” measure shows the highest reading since it was invented in 1995.

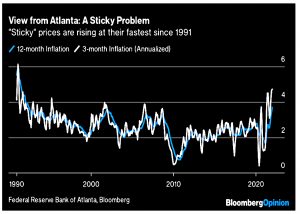

“Sticky” prices (where changing the price is difficult/takes time) are rising at the fastest rate since 1991.

Diffusion indices show that inflation is broadening:

More than 80% of components have inflation above their five-year average. This time last year, fewer than 40% had inflation this high.

The good news is that inflation might be peaking.

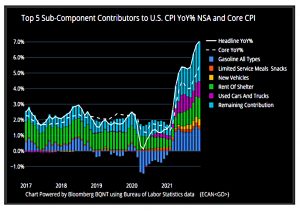

[Used vehicle prices] should almost certainly begin to drag it down before long. Gasoline remains a huge contributor to year-on-year inflation, but this should begin to fall.

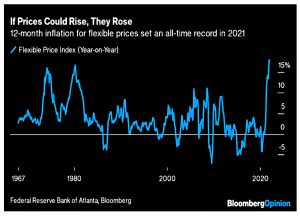

12-month inflation in flexible prices saw its greatest ever rise since the series was created in 1967.

But spikes like this in the 1970s and 1980s were soon followed by declines.

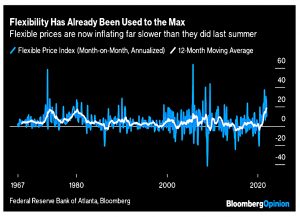

The rate of increase of prices that can most easily be moved is already dropping substantially. It’s reasonable to think that the first wave of price rises in response to the pandemic is over.

John closes with a set of questions for the next few months:

- Wage inflation: Can workers successfully demand higher pay?

- Profit margins: Do companies have the pricing power to pass higher costs to

consumers, and will they use it? - Supply bottlenecks: Omicron and the renewed disruption it is causing in Chinese

ports muddies forecasts for imminent easing of supply chains — but will that stop

the problem from dissipating this year? - Real estate: Will rents increase by as much as industry surveys suggest?

- Energy prices: Will the disruption driven by the transition to renewables drive another

year of price increases? - What the Fed will do about it?

Quite a lot to think about.

Should we worry?

Big ERN looked at whether we FIRE types should worry about high inflation.

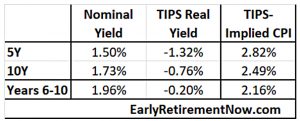

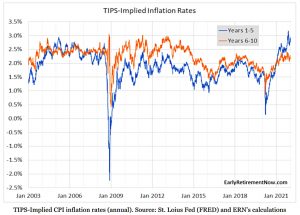

He starts by looking at the inflation rates predicted by the spread between normal Treasury bonds and the real TIPS yield.

The 5-year CPI estimate is elevated, at 2.8%. The 10-year rate is already down to 2.5%. And if we “back out” the TIPS-implied inflation rate for the years 6-10 as [1.0249^10/1.0282^5]^(1/5)-1, we get an implied inflation rate of 2.16%, not significantly different from everybody’s long-term 2% estimate.

ERN notes that the FED targets Core-PCE, which is usually a bit lower than CPI, so this is a good match.

Historically, this figure is normal – the average since 2003 is 2.25 and the peaks are over 3%.

- So the inflation outlook is not bad.

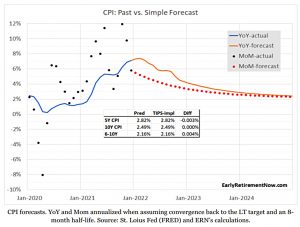

Next, ENR played around with some possible paths from where we are now to the 2.16% long-term forecast.

The year-over-year measure is bound to go up for two more months and is likely to peak at 7.4% in February of 2022. That’s because we’re still rolling out the relatively benign CPI numbers in early 2021.

The YoY numbers won’t drop below 3% until 2024.

ERN isn’t very worried about high inflation.

- He sees high equity valuations as much more dangerous to safe withdrawal rates for FIRE types.

He says it’s too late to shift out of long-duration bonds.

The future inflation and rate hikes and yield increases are already baked in. So, unless you worry about inflation and Fed rate hikes coming in worse than what is currently predicted, it’s already too late.

So you would have to expect Fed raises of more than 150 bps by the end of 2023.

Floating rate preferred shares are an option, but they have credit risk and a higher correlation to equities.

ERN admits that the Fed could get things wrong, but he remains calm:

Even if we find ourselves in an inflation spiral like the 1970s and early 80s, I should be safe because my withdrawal strategy would have survived that historical period as well.

I use ERN’s work as the basis of my own failsafe withdrawal rate, so I’m not worried either.

What tightening?

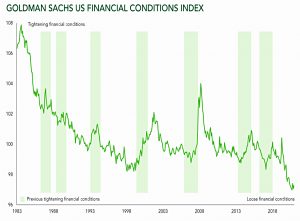

Duncan Macinnes from Ruffer reminded us that financial conditions in the US have never been so accommodative.

Does the US really need the easiest financial conditions on record? As former Federal Reserve Chair McChesney Martin once said: “the job of the Fed is to take

away the punch bowl just as the party is warming up”.

The Goldman Sachs Financial Conditions Index is a composite measure that looks at interest rates, equity valuations, borrowing costs and currency data.

- It’s currently showing an extreme reading, so even if we get the end of QE and a few small interest rate hikes in 2022, we’ll still have loose conditions – real interest rates will be significantly negative and near multi-century lows.

We are bullish on economic prospects coming into the new year. But the irony is that the stronger the economy, the more vulnerable capital markets look. What the real economy needs, financial markets can’t handle.

Ruffer has some recommendations:

Avoid the obvious beneficiaries of easy money and liquidity – profitless ‘unicorn’ technology and the Jenga tower of corporate debt. Seek out assets which benefit from strong economic activity and recovery – energy stocks for example. Own the beneficiaries of those rising interest rates: UK and European banks alongside interest rate options which hedge your portfolio duration.

Tips

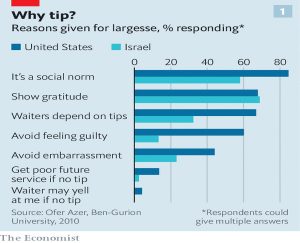

The Economist looked at whether tips lead to better service.

Economists are puzzled by the fact that so many people give tips, voluntarily handing out cash for a routine service, when it is assumed that customers generally want to pay as little as possible for what they buy.

As the chart shows, gratitude and social norms are the main drivers.

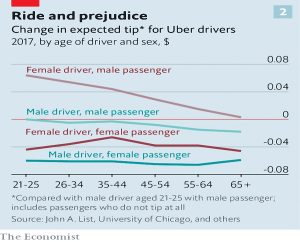

- Weather, race and gender are also factors.

During Covid, people have been tipping more for food deliveries and taxis.

This was in effect doling out danger money, as tipping rates rose along with covid-19 hospitalisation rates; in Trump-voting areas they rose less fast, as perceptions of risk may have been lower.

Tipping is less common in Europe, where a service charge is normally added to the bill or already included.

- And in Asia, it is often frowned upon as insulting.

But in India and Africa, it is expected.

One study across 30 countries suggested that tipping was more common in societies where inequality was rife and where the guilty feelings of the well-off are more acute.

The economic problem with tipping is that most customers are not regulars and a one-time customer cannot benefit from the implied future improvement in service.

- But even regulars don’t vary their tips according to service, and service in non-tipping countries (Japan and South Korea) is not inferior.

If tips are incentives, they should also be found more often in trades with high levels of customer contact.

But a wealth of professions, such as dental hygienists, car mechanics or vets, entirely lack a culture of tipping.

Tipping benefits employers as well as servers, allowing low headline prices and transferring some risk to the server.

In Britain and Germany, tips do not count towards the minimum wage. But in France and parts of America, employees in effect lose the first tips they earn to their employer.

Tipping was also historically a way around tax (since tips wherein cash) and even now service charges are outside VAT (though usually calculated after VAT is added).

Getting rid of tips also results in lower customer ratings (even though a subset of customers will claim not to like tipping) and higher staff turnover.

Perhaps [customers] like to feel that they are in control. And it may comfort servers to think that if they perform better they will be more handsomely rewarded.

Freetrade

Freetrade has announced that German stocks have been added to the platform, part of a general rollout across European exchanges in the coming months.

- The firm is pitching this as a USP for UK investors but the reality is that Freetrade is now focusing on picking up European market share.

The UK offering has stagnated in recent years – I was still unable to download transaction data when I recently started my prep for the looming end of the tax year.

- The name is starting to bug me, too – transaction costs are zero, but the free account has access to a very limited universe of stocks and has serious FX charges for US (and now German) companies.

They even charge for an ISA.

It’s yet another example (after P2P lending, equity crowdfunding and robo-advisors) of UK fintech firms launching with a fanfare of promises but disappointing in the medium term.

- I seem to be in the minority, however – Freetrade has 1M customers and £1bn in AUM and is the second-largest broker (by the number of trades) on the LSE.

Vanguard

The Economist wrote about Vanguard’s big push into financial advice.

- The firm pioneered passive funds, which now have a one-third share of the AUM of UK fund managers – Vanguard itself looks after $8.2 trn globally.

The UK retail investment market covers £4.6 trn (including pensions), and 36K financial advisers live on the fees earned on this pile.

- At the same time, there are around 12M people with more than £10K in savings and no advisor.

I would like these people to read blogs like 7 Circles, but Vanguard has now set its sights on them.

The key to making advice work for those with small pots is to reduce costs through automation and algorithms.

The Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) estimated in 2020 that the average cost of investing with a traditional adviser was 1.9% of the assets invested each year. For an automated one, that fell to 0.8%.

That’s still too high for me, as costs compound down the years:

If you invest £100,000 in assets that grow by 5% a year for 30 years and pay an annual fee of 1.9%, you end up with £246,074. If the fee falls to 0.8%, you end up with £340,577.

And if you pay no fees at all, you end up with £432K.

But as usual, I’m out of step with the public:

- Vanguard added advice (at 0.79% pa, and targeted at clients with £50K in assets) in April 2021 and close to doubled its number of UK clients to 361K, and £11.8 bn in AUM.

It added 183K people, up from 100K the previous year.

- Perhaps Vanguard will succeed where the robo-advisors have – to date -failed.

Quick Links

I have seven for you this week, the first six from The Economist:

- The newspaper looked at how gummed up supply chains are

- And at Unilever’s bid for Glaxo’s healthcare business

- And asked what ExxonMobile’s climate strategy is worth

- And wrote about Big Tech’s ambitions

- And examined what the largest tech firms are investing in

- And explained why Microsoft is spending $69 bn on video games.

- LT3000 took issue with Graham’s “weighing machine”.

Until next time.