Weekly Roundup, 17th May 2016

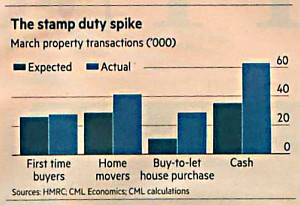

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup in the FT, with the Chart That Tells A Story. This week it was about Stamp Duty.

Contents

Stamp Duty

The chart shows that the introduction of the new 3% extra stamp duty on second homes and buy-to-let led to a spike in sales in March.

- There were 162K transactions compared to an expected 100K.

The Council of Mortgage Lenders broke the figures down by type of buyer.

- Not surprisingly, cash buyers (who are mostly landlords) had the biggest spike in terms of numbers, and buy-to-let (with a mortgage) showed the biggest spike in percentage terms.

No doubt the market will now quieten down from April ((This would be bad luck for me, as my mother-in-law’s 2-bed flat hit the market after the surcharge was introduced ))

- This is partly down to stamp duty but also because of nervousness around the Brexit referendum.

St Ives

We’ll come back to Brexit in a moment, but first let’s stick with second homes.

The Economist had an article about the vote in St Ives to restrict new homes from being bought by those who already have a house elsewhere.

- Only 1% of English homes are the second home of English people, but in central St Ives, 25% of homes have no local owner.

The newspaper calls the vote wrong-headed.

- Restricting the sale of new homes depressed their price, meaning that fewer will be built.

Prices of existing houses could go up, or holidaymakers could go elsewhere ((Though speaking from experience, St Ives has no direct competitors ))

- Locals could even sell their existing houses to incomers.

Something similar happened in Switzerland, and research suggests that prices went down by 12%.

Even the stamp duty surcharge is a better solution than a ban.

- But best of all, as usual with our discussions of house prices, would be to build more houses.

Brexit briefing

This week’s Brexit briefing picked up on David Cameron’s comments that Brexit would lead to world war three.

- Hyperbole aside, there have been reasonable questions asked about whether Britain would be less secure outside the EU.

Opinion in the security industry appears to be divided about whether there would be a realistic impact.

- NATO and the “Five Eyes” intelligence network (UK, US, Canada, Australia and New Zealand) are arguably more important.

Certainly some EU members have proved less reliable than others.

- I think I’ll be able to sleep at night, even if we leave the EU.

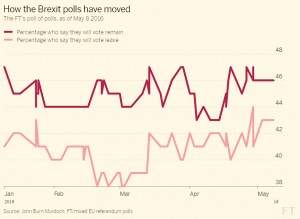

Brexit bookies

The newspaper’s second Brexit article was about the bookies.

- Although the opinion polls have been wobbling, the betting markets have been firmly behind Remain throughout the campaign.

Neither polls nor bookies got the 2015 election right, but bookies were closer, just as they have been in US presidential elections (from 1988 to 2004).

- Bookies are more accurate because the participants are estimating risk, rather than expressing an opinion.

- There’s also a built-in bias towards change in opinion polls (self-selection).

But the bookies didn’t see a Trump victory in the Republican nomination, and the current betting spread (68% Remain, 32% Brexit) is still too close to call in a two-horse race.

- But that’s the way to bet.

Brexit roulette

In the FT, Naomi Rovnick and David Stevenson took a look at the “strategic bets” you might place on what the markets will do after the referendum.

The FTSE-100 hasn’t been too affected, since many of its companies make a lot of their money outside of the UK.

The FTSE 100 VIX (volatility index) remains calm.

- But UK-focused stocks like Lloyds and Next have been hit.

The polls are backing Remain.

- If you think that we will vote to Remain, any weakness could be a buying opportunity.

A vote to Leave, on the other hand, might produce two years of weakness in the UK market, and push the pound down against the dollar and the euro by up to 20%.

- The pound has been falling already against the dollar and the euro.

To guard against the risks, the FT recommends global diversification rather than outright hedging.

- Hedging can work well in the short-term, but in the long-run, the costs generally outweigh the benefits.

If you do want to hedge, the place to start is with currency-hedged ETFs and investment trusts, though with a big fall in sterling the key risk, this seems counter-productive to me.

- There are also plenty of short and leveraged products for more overt gambling on the result.

If you expect Brexit, short sterling against the dollar particularly (since Brexit could be seen as bad for the euro as well).

You might also sell the FTSE 250, particularly housebuilders and consumer discretionary spending stocks, like travel. Financial services would also do badly.

- Of course, if there is a sell-off later in the year, that could prove a long-term buying opportunity.

David also thinks gilt wold be worth a punt, with the Bank of England intervening in the face of foreign selling.

If you expect a Remain vote, most asset classes should benefit from a relief rally, though gilts might sell off a bit.

Looking at the Eurostoxx index for last year (when the Greeks voted to accept another bailout) gives support for this idea.

The article also noted that retail investors have started to short the FTSE-100 and FTSE-250.

- This is normally a good contrarian indicator.

Fund charges

Merryn’s column was about how difficult it is for fund managers to justify their charges.

In the hey-day of funds (say thirty years ago), they made more sense.

- Trading was difficult and information hard and expensive to come by.

- The “experts” could deliver better returns than you, and cream some money off the top.

- And the best managers (Anthony Bolton, Peter Lynch et al) could stay at the top year after year.

Now it seems impossible for managers to remain top quartile, and the lower returns generally make the fees stick out a mile.

- In fact, cost is now the best predictor of a fund’s performance – cheap funds do better.

Inflation

Tim Harford’s column was about measuring inflation.

Argentina has had a problem with inflation for years, and after declaring implausible numbers for some time, abandoned inflation measures altogether in late 2015.

So Alberto Cavallo of MIT began to collect online prices.

- He worked out that inflation had been 20% pa from 2007 to 2011, when official figures had said 8%.

The “Billion Prices Project” (BPP) collects that many prices each week, across 60 countries.

- As well as disproving the Argentinian numbers, they confirmed the US figures, despite many people looking in vain for the hyperinflation they were sure that money printing and QE would lead to.

The BPP numbers are also available (via PriceStats) each day, rather than once a month like official figures.

Tim also talked about the problem of adjusting for quality – something that feeds into my dislike of GDP as a measure. ((We’ve looked at this once before, but I plan to return to the topic soon ))

- Tim gives the example of a $20 Edison phonograph in 1899 versus an iPod Nano at $145 today ((An iPod? Do people still use a separate box for songs? ))

- There’s no good answer to what the implied inflation rate over the intervening 117 years should be.

That’s an extreme example, but most commercial goods are introduced at a premium price and gradually discounted until they are replaced with a better model.

- Using the BPP’s “big data” approach of measuring many prices of many individual but comparable goods, making these adjustments becomes easier.

Tim also talked about why recessions happen.

The theory is that prices don’t adjust smoothly downwards.

- So inventory of the now over-priced item builds up, retailers stop ordering and manufacturers go bust.

- The problem is that official inflation figures suggest that prices do move smoothly up and down.

This is a statistical illusion.

- Officials have been averaging the change in prices over the periods in which they occur.

- For example, a 1% change might be spread across five months at 0.2% per month.

BPP data suggests that small price changes are rare, and several percent at a time is more usual.

- Repricing in real-world stores is even harder (re-labelling is involved) and so is likely to be even less common.

So price stickiness is real after all.

Lending club

Both the FT and the Economist reported on the ousting of the founder of the original P2P lender, Lending Club.

- Rene Laplanche was involved in selling $22M worth of the wrong loans to investment bank Jeffries – the dates had been changed to make it look like the loans had originated after changes to Lending Club’s rules.

- Lending Club has had to buy the loans back.

- Laplanche had also covered up a personal stake in Citrix Capital, a firm that had been both buying from and selling to Lending Club.

Like other innovative finance products, P2P was bound to have a scandal at some point.

- Unfortunately this one looks very similar to the bundling of sub-prime loans with dodgy paperwork back in 2008.

Lending Club’s shares hadn’t being doing well before the scandal.

- The P2P business model involves one-off fees rather than ongoing interest, so more investors and borrowers are needed all the time.

- It’s hard to grow like this without risking credit quality, and the institutional investors that have been the recent focus of P2P lenders are starting to become concerned.

The Economist predicts a return to the industry’s retail investor roots.

- Which may be no bad thing, in the UK at least.

The FT highlighted moves by UK lenders to reassure investors that they are safe.

- UK regulations have been written specifically for P2P, whereas US lenders follow pre-existing rules.

- At the same time, none of the UK companies has full regulatory status, operating instead under interim permissions.

- But the industry body – the P2PFA – does at least insist that its members publish their loan books, reducing the risk of fraud.

Surge pricing

Anyone who’s tried Uber probably likes it.

- The service is terrific and the price is right.

Except when it’s surge pricing, which the Economist looked at.

- When the pubs or clubs kick out, near a concert or sports event, in the rain or a transport emergency, Uber puts its prices up.

- And not just a bit – they use multiples of the original fare.

The idea is to draw more drivers into the area – they get a cut of the extra fare – and clear the surge in demand by matching it with a surge of supply (and scaring off some of the demand with high prices).

- The waiting time should come down, and the completion rate (percentage of passengers matched with a driver) should go up.

And it works.

- To prove it, Uber released data from an Ariana Grande ((Not an artists I follow )) concert in March, and compared it to New Year’s Eve 2014, when Uber’s surge pricing algorithm failed.

The chosen events probably exaggerate the effect, since drivers already know to be outside a concert venue when the show ends.

- But even so, the possibility of a surge fare would encourage more drivers to be there, meaning that the surge fare is less likely to be needed.

Eventually Uber would like to use data mining to anticipate where demand will arise, and send cars into the area without using surge pricing.

- This is likely to become easier when they switch over to driver-less cars.

Reducing debt

Buttonwood looked at how to reduce global debt.

There was a debt bubble from 1982 to 2007.

- During the financial crisis, people worried that the paying down of private debt might lead to continued depression.

- Instead, governments (both rich and poor, especially China) took on more debt.

- Instead of global deleveraging, debt levels increased, their burden softened by record low interest rates.

- The problem is that lots of debt makes it difficult to raise rates, and continued low rate lead to more debt.

To cause a repeat of 2008, we need three things:

- a fall in asset prices

- debtors concentrated in rich countries

- exposure to the debt from global investors

But this time around, the debtors include emerging market (EM) governments and commodity producers.

- Only China has a significant global impact, and most of its debts are held domestically.

But we still need to get rid of the debt in the end.

Normally inflation is the way, but most countries can’t generate even their 2% pa targets, and the political will for high rates maybe lacking.

- Some people want a debt forgiveness program, but this would cripple the financial sector and lead to a new crisis.

An alternative is a weak form of debt for equity swap.

- Morgan Stanley would like to see more GDP-linked debt (as is already available in the UK and US).

- This would mean that debt-to-GDP ratios would remain flat in a downturn.

- Irredeemable debt could also be used to avoid refinancing crises.

Two other useful measures would be removing the tax advantage of debt finance over equity (not allowing interest to be deductible) and shared-equity mortgages, where lenders own part of the house.

All these ideas seem helpful, but most can’t be retrofitted.

- So the debt will be with us for the foreseeable future, and another crisis hangs over our heads.

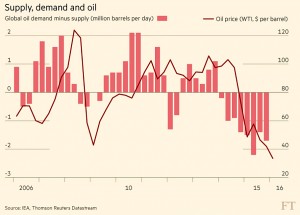

Oil

John Authers took a look at the stories for the future of oil at the annual conference of the CFA institute, an industry body.

He first warned about the peal oil story from the same conference in 2008.

- Oil prices were heading to $150 per barrel at the time, and Peak Oil fans predicted that finite supply would lead to ever higher prices as production declined.

Of course, higher prices led to higher supply, mostly from fracking shale.

- Alternatives have also attracted investment and the oil price is down 80% from its 2008 high.

So this year’s stories also need to be taken with a pinch of salt.

Story number one is that technology will mean that less energy is required.

- Chinese demand is unreliable and climate accords mean that oil is the energy of last resort.

- Producers desperate to avoid “stranded assets” will pump more oil at each fall in demand, pushing down prices.

Story number two is also about low prices, but from a geo-political viewpoint.

- Now that the US is self-sufficient in oil, it can ignore conflict in other oil-producing regions.

- The global market for oil will split into regional markets.

- The US market will have a ceiling close to current levels, because of shale production.

- The rest of the world could have price spikes as conflicts make supply erratic.

- Asia in particular is a big importer of oil from far away.

Two plausible stories, but so was Peak Oil in 2008.

- People have a need to hear the reasons why things will stay the way they are now.

You have been warned.

Until next time.