Weekly Roundup, 24th May 2016

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup in the FT, with Merryn Somerset-Webb, who was looking at pensions.

Contents

Pensions

Last week, Andy Haldane – the Bank of England’s chief economist – claimed that he was not able to make “the remotest sense of pensions”.

- Merryn, like me, is flabbergasted. ((Personally, I fear this is the start of another spin campaign before yet more “simplification” – let’s hope not ))

Pensions are simple. There are two flavours:

- Defined benefit (DB) pensions are very simple – you work, and this qualifies you for money when you stop working. The amount is known in advance and guaranteed.

- Defined contribution (DC) pensions are also simple – you and your employer pay into a pot of money which hopefully grows over time and you try to live off it when you retire. You get to take the first 25% tax-free, and the rest is taxed as income (as is the DB pension).

The real problems with pensions are getting people to understand that they will need one, and then getting them to contribute enough money towards their retirement.

- Auto enrolment should help here in time.

Resource allocation

Tim Harford begins his FT column by quoting Lionel Robbins’ definition of economics: “the science which studies human behaviour as a relationship between ends and scarce means which have alternative uses”.

- Or as Tim puts it, “the study of who gets what and why”.

- I would agree that resource allocation is central to economics, and indeed to politics.

But where Tim and I would disagree is the extent to which a market solution to resource allocation can be used.

- Tim uses several emotive examples of where allocation to the highest bidder would be inappropriate – school places, passports, spare kidneys).

I would argue that given suitable controls, and in the context of a civilised and stable society, markets could be set up in all three of those situations.

- It’s really more to do with what you call a fair allocation.

- And fair is a word that means something different to everyone.

So Tim’s article is about alternative “matching mechanisms”.

- He uses matching teaching hospitals to trainee doctors. They each want to match with good examples of the other. Beyond this, there will be location and specialism issues, and some doctors may want to attend the same school as a partner.

A good matching system – as defined by Tim – would not only satisfy as much of that as possible, but would discourage “gaming” the system by students asking for (and getting) a compromise solution.

- I fail to see the issue with such “gaming” – or being sensible, as I would call it – if all students have equivalent information.

Apparently Alvin Roth – who wrote a book called Who Gets What – and Why – and his colleagues have devised superior matching mechanisms, though we don’t get to hear about how they work.

[amazon template=thumbnail&asin=0007520786]

Now Will Jones and Alexander Teytelboym from Oxford want governments to use similar mechanisms in the refugee crisis.

- The problem is essentially which refugees go to which country, and to which city / area within that country.

- The availability of services such as housing and medical care are complications.

The candidate mechanism involves “trading cycles”.

- It’s a bit like the single transferable vote system in proportional representation, or the way we pick football teams in the playground.

- Mutual first choices are matched in round one, and in round two people pick again amongst what is left.

This all sounds like deck chairs on the Titanic to me.

- The real problem is what to do with the millions of non-EU citizens who would like to live in the EU, and the millions of non-UK people who would like to live in the UK.

- The secondary problem is how to involve existing communities in the decision of whether refugees should join their community.

But it’s definitely a resource allocation problem.

St Ives again

I managed to find another article about St Ives, so I’m using this as an excuse to talk about it again.

- India Knight in the Sunday Times ((No link because it’s behind a pay wall )) is also against the proposed ban on new houses for second home owners.

India has been going to St Ives each summer for almost 20 years, which is a bit longer than me.

- As she points out, it is not Kensington-on-Sea – that would be Padstow or Rock.

- St Ives is a mixed holiday community, with chips and pasties as well as crab sandwiches and sea-bass.

- here are normal B&Bs as well as pricey rental cottages.

She fears the same things as me – the ban will force developers away, and house prices up.

- And if it also drives tourists away, the town’s economy will be seriously damaged.

More housing is needed, not less.

- But the locals won’t ever be the ones buying the cottages with sea-views.

Unless the town is already dead.

Brexit briefing

This week’s Brexit briefing in the Economist was about agriculture.

- Most farmers would like to Leave – despite the National Farmers Union wanting to Remain – even though this would mean that they lost out.

The Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) is one of the chief embarrassments of the EU.

- It takes up 40% of the EU budget to achieve very little beyond the wine lakes and butter mountains of the 1980s.

But the fact remains that EU farm payments – often to keep land fallow – make up 54% of UK farmers’ income.

- And the EU takes 62% of UK farm exports.

Another irony is the fear of immigration expressed by rural farmers, despite their reliance on seasonal migrant workers for harvests.

The UK farmers believe that the French get better treatment from the EU, and that Brexit would remove red tape.

- But to date, the UK government has been one of the cheerleaders for the green regulations they dislike.

Brexit and investors

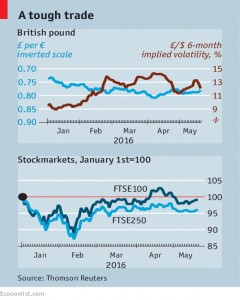

Buttonwood looked at the market reaction to the referendum.

- Professional investors (fund managers) are afraid of Brexit, but think that it is unlikely.

The biggest impact would be a fall in the pound, so make sure that you have some foreign assets.

- Of course, a Remain vote might push up the pound, so don’t go too far.

The impact on stocks will be harder to predict, since many of the largest UK stocks are foreign, or have significant foreign earnings (which should rise on Brexit).

- The FTSE-250 is likely to suffer more than the FTSE-100, and has lagged so far this year.

Bonds should also be suffering, since a fall in Sterling would lead to lower interest for foreign holders.

- They ought to demand a higher yield to compensate.

- But gilt prices have held up so far.

- This is probably because Brexit would lead to an interest rate cut and further QE, which would be good for gilts.

Apple, Buffett and Didi Chuxing

The Economist took a look at Warren Buffett’s purchase of $1bn of Apple shares, just as Carl Icahn sold $5bn of Apple.

- Does this mean that Apple is now a “mature” rather than a “growth” company?

- And why has Buffet broken the habit of a lifetime to buy into a tech firm? ((He has a – so far unprofitable – stake in IBM but this is arguably now a services firm rather than a tech firm ))

The first thing is that $1bn is only 0.3% of Berkshire Hathaway’s capital.

The second thing is that the stake wasn’t bought by Buffett but by one of the two investment managers he appointed a few years ago.

- Perhaps it just means that Apple is cheap.

As Buffett bought Apple, so Apple bought $1bn of Didi Chuxing, the Chinese version of Uber.

- This deal is really a favour to the Chinese government. Apple generates 25% of sales there, and its online stores are banned.

- Didi is losing billions each year in a price war with Uber.

The alternative interpretation is that Apple’s growth phase is over, and it will now succumb to speculative bets on projects not related to its core competences.

- It has a massive cash pile that it can’t repatriate – too much to use for dividends and share buy-backs.

Herein lies the danger.

- As the Economist points out, the only person with a long-term track record of success in allocating billions of dollars of other people’s money is Buffett himself.

Death of a bull

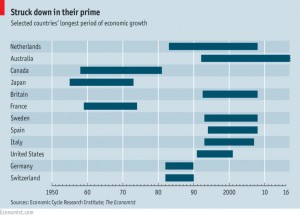

The Economist also looked at what brings a period of economic expansion to an end.

- The US expansion is seven years old in June, and people are starting to get twitchy.

- Only three booms have lasted longer, the record being ten years in the 1990s.

Janet Yellen has stated that “it’s a myth that expansions die of old age”, and the newspaper agrees.

- Recessions (two quarters of falling GDP) start with supply shocks (oil price rises in 1973) but more often with weak demand.

- A market crash can make people afraid to spend, which leads to rising inventories and falling production.

But other countries have expansions much bigger than in the US.

- The Netherlands managed 26 years to 2008, and Australia will equal this in 2017. So the “natural” lifespan is much longer than seven years.

The Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco put together an actuarial table for US expansions.

- They found that before the second world war, the odds of recession rose with the age of an expansion.

But for the 12 post-war expansions, there was no such link.

- Though a continuing boom seems counter-intuitive, it makes more sense when thought of as a series of consecutive sector booms, concluding in an export boom driven by currency weakness.

Since the Depression, Governments have played more of a role in counteracting natural shocks, making expansions longer and recessions shorter.

- And sometimes (for example the US and UK in the 1980s) they have actually triggered recessions to bring down raging inflation.

But since policy works only belatedly if at all, bad timing from a central bank can cause a recession – for example, through one interest rate rise too many.

- The currently reliance on unfamiliar tools (QE, ZIRP and NIRP) increases the risk of error.

Worrying too much about high inflation seems to be a problem.

- In Australia there is a target range for inflation (2% to 3%) which seems to help with avoiding recessions.

Let’s hope the Fed – which has already raised rates with inflation below its target – doesn’t get carried away this summer.

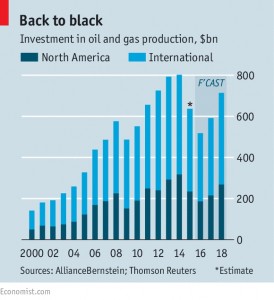

The new greens

The Economist also reported on the new environmentalists – the shareholder activists hoping to put pressure on Big Oil.

- Four of the five largest listed oil companies face resolutions to force them to outline risks from climate change regulation.

- They would also like to see a reduction in investment.

- 49% voted for a similar resolution at Occidental and 42% at Anadarko.

- Similar campaigns have already succeeded at Shell and BP.

ExxonMobil – the largest firm – argues that more energy is needed to continue to alleviate global poverty (see below) and that technology and a carbon tax will prevail.

- This year’s resolutions will probably fail, but the direction of travel is clear.

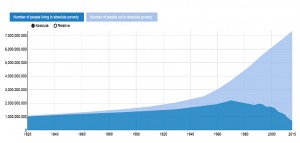

Poverty

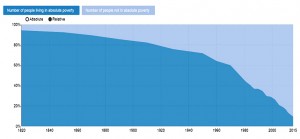

And finally, for those sceptical about the good works of capitalism, here are a couple of charts (from ourworldindata.org) showing how global poverty has changed over the last 200 years.

In absolute terms, we haven’t made that much progress.

- There were close to 1bn people in poverty in 1820 and not many fewer today.

But in percentage terms, things look much better.

- More than 90% of people lived in poverty in 1820, and that figure didn’t get below 80% until the end of the first world war.

When I was born, more than 60% of people lived in poverty.

- But despite a massive increase in global population since then, today only 10% live below the poverty line.

Something to cheer at last.

Until next time.