Weekly Roundup, 19th November 2019

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup in the FT, which had several articles about investment trusts.

Investment trusts

With the UK election now underway, there was little of interest in the financial media this week.

Emma Agyemang’s article was about trusts backed by wealthy families.

- The idea is that the people running the trusts have skin in the game, which is the title of an annual report on trusts from Investec.

Boards and managers have invested a total £3.4bn in their trusts. The largest investment by a manager was the Rothschild family, who invested £703m in RIT Capital.

The family trusts fall into two main categories:

- Diversified international stocks (and perhaps bonds)

- Brunner

- Majedie Investments

- Witan

- A flexible (and dynamic) investment strategy across many asset classes

- Caledonia

- Hansa

- RIT Capital

Brunner, Caledonia and Witan all feature in the AIC’s “dividend heroes” list of trusts that have increased their dividends for 20 or more consecutive years.

There are also non-family-dominated trusts which sit in the second category:

- Ruffer

- Personal Assets

See our Investment Trusts page for more details.

- You might also want to check out our sheet of Family Firms.

Merryn Somerset Webb ‘s article focused on the longevity of investment trusts.

- Her intro was about a Longevity conference that I attended last week (and might write up soon).

Last year, the oldest of the lot (and one I own) celebrated its 150th birthday — the F&C Investment Trust. Dunedin Income and Growth is 146 years old.

Scottish American is 144. The JPMorgan American Investment Trust is 136 years old and The Mercantile Investment Trust is 133.

Merryn points out that the structure of ITs is great for holding illiquid assets and anything you want for the long term.

It takes a while to sell a solar farm, an airport or portfolio of unlisted companies. Just ask Neil Woodford.

Permanent capital also attracts good managers, lured by the opportunity to manage money and be a genuine long-term investor without the endless distractions of investors buying and selling units.

And because they are listed companies, the board of directors – which is independent of the fund manager(s) that they hire – has a legal duty to look after the interests of shareholders.

She also finds them suitable for producing an income (see below), and most importantly:

Investment trusts have a long-term record of outperforming open-ended funds.

Lucy Warwick-Ching’s article was about IT dividend heroes.

Investment trustshave to pay out 85% of their profits to investors each year — but can keep 15% in cash reserves.

This allows them to build up reserves in years of strong corporate dividend growth which can be used to maintain steady income payments when corporate profits are under pressure.

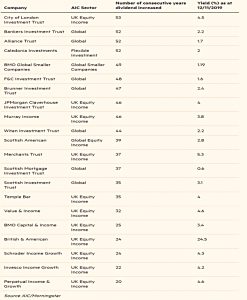

Lucy provided a list of 21 heroes that have increased their dividend for 20 years or more:

Only seven of the dividend heroes currently yield over 4% pa, and just three have delivered inflation beating dividend increases every year over the past 20 years — the Bankers trust, Caledonia and JPMorgan Claverhouse.

Personally I prefer a total returns approach, but I realise that some investors find a regular income comforting.

That’s entertainment

The Economist had a couple of articles (1 and 2) on creative destruction in the entertainment business.

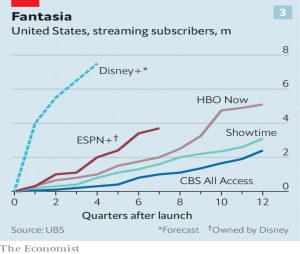

- Disney and Apple have recently joined Netflix, Amazon and Google (YouTube) in the streaming wars which now cover 700M subscribers globally.

Netflix broke the mould in 2007 by using broadband connections to sell video subscriptions, undercutting the cable firms. The firm has acted as a catalyst for competition, forcing the old guard to slash prices and innovate, and sucking in new contenders.

In 2013 Netflix released Season One of House of Cards all at once.

- This started the age of bingeing.

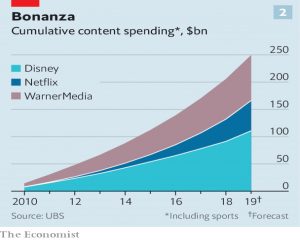

No firm has more than a 20% share, but the $100 bn being invested in content this year is around the same amount as will go to the US oil industry.

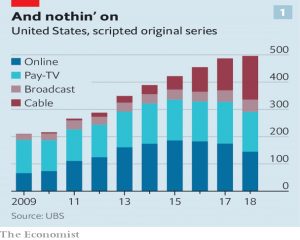

Last year 496 new shows were made, double the number in 2010.

The business model is now largely subscriptions rather than advertising, but the big firms are burning too much cash, which means there are risks ahead.

Telecoms and airlines in America saw a riot of competition in the 1990s only to become financially stretched and then reconsolidated into oligopolies that are known today for poor service and high prices.

The Economist sees a role for regulation:

- Preventing any one firm from reaching a dominant share of the market

- Forcing platforms (iOS and Andriod, as well as ISPs and set-top box providers) to remain open access, and

- Ensuring portability of personal data across platforms.

US pensions

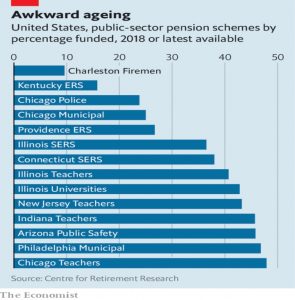

The newspaper also had two articles on the state of US pensions (1 and 2), which are severely underfunded.

- Some schemes have less than 50% funding.

The Illinois Teachers deficit is now $75 bn, or $6K for everyone living in the state.

- Since being formed in 1939, there has not been a single year where the fund has received enough contributions to fund its promises.

Three-quarters of the money the state (or rather the taxpayer) now pays in each year merely covers shortfalls from previous years.

With people living longer, the cost of providing pensions is increasing.

- But attempts to retrospectively cut benefits usually get thrown out in the courts.

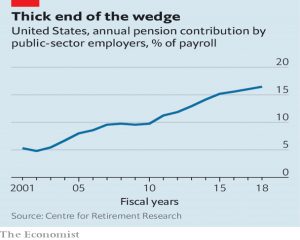

Contributions have risen from 5.3% of payroll in 2001 to 16.5% today.

Even so, in no year since 2001 has the average employer contributed as much as demanded by actuaries.

Some schemes are betting on “alternative assets” like hedge funds and private equity to fill the gap. But hedge-fund returns have been disappointing over the past decade, and the private-equity industry is not large enough to absorb $4trn of public-sector pension assets.

The underlying problem is that public-sector pension schemes are allowed to use an assumed rate of investment return as their discount rate for future liabilities.

- Many assume more than 7% pa going forward, even if this is much more than they have achieved historically.

Even under this system, the average funding ratio is only 72% and the hole is $1.6 trn.

In the worst-affected states—Connecticut, Illinois and New Jersey—pension costs in 2014 were already 15% of total revenues.

Some states and cities will soon enter a downward spiral, in which pension costs lead to bad public services or tax rises, in turn encouraging workers and firms to move out, which then shrinks the tax base, making promises even less affordable.

The private sector views pension promises as debts and typically discounts using corporate bond yields.

- In my opinion, this is also wrong and is the main reason why so many final salary schemes have closed.

But at least the error results in the fund behaving too conservatively, rather than ignoring a serious future problem.

Quick Links

I have just two for you this week:

- Alpha Architect looked at the impact of the Investment Factor on returns

- And Musings on Markets wrote about the SoftBank/WeWork endgame

Until next time.