Weekly Roundup, 28th October 2015

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup in the FT, where it was Judith Evans week.

Contents

Stamp Duty hits central London property

Judith had five pieces worth reading this week, the first of which was a report on London’s slowing prime property market.

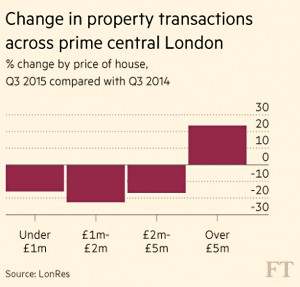

Sales are down 14% in the third quarter compared to 2014, and prices have been cut on 35% of homes. Others have been renovating rather than selling.

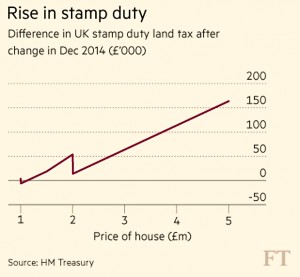

The rise in stamp duty in the budget appears to have been the catalyst. In the £1M to £2M band, where the increases start to be felt, ((The breakeven point is £937K )) sales are down 22.5%. In the £2M to £5M band the drop is 16.9%.

Whether this a bad thing depends on what happens next. If prices fall somewhat, few will be unhappy.

But if the market locks up, and that lockup then begins to trickle down to cheaper London properties, and then spreads outside the capital, the Chancellor make have to act before the next election.

Financial advisers don’t publish charges

Judith also reported on the reluctance of IFAs to publish their fees, making it difficult for potential customers to shop around.

More than two-thirds leave their fees off their websites, while only 2% of firms provided what Which? called “genuinely useful information”, such as a breakdown of charges.

Ten percent refused to give their fees over the phone, saving them for the face-to-face sales pitch.

This all very regrettable if not surprising, but since the switch to up-front fees, not many people can afford an IFA in any case.

Which? compared fees on a 25% lump sum withdrawal from a £150K pension pot, with the rest going into income drawdown. Quotes averaged £2,500 or 1.7%, but 15% of advisers quoted more than £4K and some went as high as £7K (more than 4% of the pot).

Any of us that can afford that kind of money would still be better off looking after our own affairs.

People generally seem to be coming to the same conclusion: the FCA says that two-thirds of financial products are now sold without advice, compared to 40% three years ago.

Buy to let trust closes

The UK’s first buy-to-let REIT is to close less than a year after listing on AIM.

The Mill Residential Reit had said it wanted profit from “Generation Rent” but is now requesting shareholder approval to de-list after failing to attract enough investment. It needs 75% agreement to go ahead.

It could take up to 10 months to return around £3.05M in cash from the £3.5M partly crowd-funded IPO last year (a 13% haircut). Shareholders include HL customers as the fund was listed on that platform.

The fund bought seven properties in London, Surrey and Bristol, but setup costs and fees exceeded net rental income in its early months. As the net asset value fell, it proved difficult to raise further funds.

Police warn on airport parking

Police have warned that pensioners are being targeted by a scam involving buying parking spaces near airports. ((I get contacted about this on every week ))

The MO matches that used by peddlers of diamonds, wine and carbon credits – a hard sell, sometimes followed by a Ponzi-style initial “dividend” while the scheme is still being marketed to others, then nothing.

Avoid.

Investment trusts

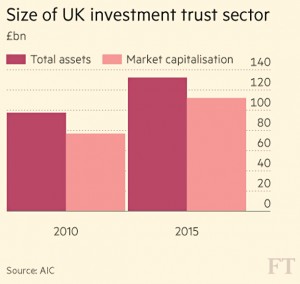

Judith’s main feature of the week was a report on the Investment trust (IT) sector. There are more than 400 trusts listed in London, and they have grown by 45% over the past 5 years, from £77bn to £112bn.

As well as the old standard UK and international equity funds, ITs have taken on new asset classes – renewable energy, P2P debt etc – and there have been UK launches by US companies.

The Retail Distribution Review (RDR) in 2013 removed the advantage of upfront and trail commissions from open-ended funds (OIECs, or unit trusts), levelling the playing field.

IT’s have other advantages, such as dividend smoothing and the use of gearing.

They also have a limited number of shares in issue, so they are not motivated to keep marketing themselves to investors to increase their fee-producing asset base.

The closed nature of the fund also means that selling by investors puts no pressure on the managers of the fund to liquidate the underlying assets. This makes ITs particularly suitable for less liquid assets (everything except equities and government bonds, essentially).

Historically a discount to net assets has been another advantage, but the renewed popularity of ITs means that discounts have been narrowing.

There has also been activist shareholder activity, with 127-year-old £2.7bn Alliance Trust the latest “victim”. ((Or the most recent fund to profit, depending on your point of view ))

Following agitation from US firm Elliott, the trust has created a more formal split between it and its internal asset management arm, and will now pay the latter 35 basis pa going forward.

A new benchmark and performance targets were also introduced, alongside a fully non-executive board. Share buybacks will be used to reduce its discount to below 10%.

The 117-year-old British Assets Trust switched fund manager from F&C to BlackRock in February, changed its mandate from equities to multi-asset income.

It’s now called BlackRock Income Strategies and targets UK pensioners looking for a steady income. Another 8 trusts have switched management teams since the start of 2014.

There are still a few problems for the sector to resolve, though:

- Some 130 investment trusts have market capitalisations of less than £50M, which may be fine for a small cap trust, but investors would be safer looking at £100M – £200M for a regular IT, to ensure liquidity.

- More than half of trusts still have performance fees, which are hard to defend in mainstream sectors.

Feels like 1997

Ken Fisher came across all Nostradamus. He thinks that it feels like 1997 all over again.

More specifically, he is drawing parallels between two recovery bull markets.

He listed the similarities, which are mostly in the US. Some are better than others:

- The boom and bust in US housing matches the US Savings & Loan crisis of 1989-90.

- Tarp was the recent clean up programme, and the Resolution Trust Corporation the earlier one.

- Early in both recoveries, Europe had a double-dip recession – the debt crisis in 2010- 12, the ERM crisis in 1992-93.

- Democrat Barack Obama was elected as president with control of both houses of Congress, like Bill Clinton in 1992.

- Both tried to re-organise healthcare; Clinton failed, Obama succeeded.

- Both men lost their majority, and faced gridlock with uncooperative Republicans.

- There were government shutdowns in 1994, 1995 and 2013.

- And Clinton oriented scandals – Bill and Monica then Hilary and Benghazi now.

- Israel elected Benjamin Netanyahu in 1996 and 2009.

- Syria’s civil war and refugee crisis parallel the 1992-95 Bosnian War.

- The Ebola scare was like the 1997 Asian flu panic.

- Emerging markets currency fears are high today, as in 1997 and 1998.

- Quebec voted against independence in 1995, and Scotland last year.

- Donald Trump’s “rich outsider” presidential run is like Steve Forbes in 1996.

More important is the yield curve spread. Banks borrow at short-term rates and lend at long-term rates, so wider spreads make lending more profitable and boost growth.

The developed world’s “recent” yield curve correlates with the 1989-1997 period.

Rates (and inflation) were higher then, but the progression matches:

- Before both the S&L and 2008 crises, the US spread turned negative.

- Then it jumped, gaining 3.83% December 1989 to May 1993, and 3.84% from July 2007 to June 2009.

- Later it sank – 2.6% in a year in 1994-95 and 1.9% in 2011-12.

- US GDP growth was slow at the start of each bull market – 2% from 1990 to 1993 and 2.1% from 2009 to 2012.

- The spread then rose again – 1.36% from January to May 1996 and 1.36% from May to December 2013.

- After that, a long downward drift.

There’s also a drop in commodity prices that matches.

The fear today is that higher long-term rates will arrive, just as after 1998. Ken is in favour of this, as the steepening yield curve then led to growth and amazing stock returns.

The 1990s bull market ran three more years with this backdrop. Perhaps history will (almost) repeat itself.

The oil market

Merryn warned about taking bets on the oil price. She thinks that a lot of what we are told about the market is nonsense.

In a normal market, we would look at the capital cycle:

- At the beginning of a cycle, demand rises fast and supply is limited.

- Prices and profits go up, which brings capital investment into the sector.

This was the case with commodities until China started slowing in 2011. What’s unusual about oil is that the current low prices and lower profits aren’t leading to lower supply.

Merryn went to a myth-busting talk by Spencer Dale:

- The first myth is that oil is “an exhaustible resource”. This is the “peak oil” argument.

- But new reserves are found constantly and proven reserves of oil are 250% of the 1980 figure.

- The second is that oil “must eventually run out”, given that demand for oil will always rise.

- But anti-emissions regulations suggest that demand will not rise indefinitely.

- The G7 has demanded no fossil fuel use beyond 2100.

- Demographic changes and the continued development of China into something closer to a rich country are further headwinds

- So are technology-facilitated car-sharing initiatives of all hues.

- So maybe oil will last forever, and prices need not rise.

- The third myth is that OPEC can control the price of oil and so will eventually slash supply to do so.

- Here’s where it gets a bit game theory-esque.

- If the Saudis know that prices probably won’t rise much anyway, it’s not in their interest to cut production, as they won’t make more money in the long run.

- US supply is falling, but by less than expected (there are no new rigs, but they’re getting more out of existing ones) and Iran is returning to global markets.

- So maybe supply won’t fall.

Merryn also quotes research by BCA which suggests that commodity prices as a whole are still 40% above their 400-year mean.

And – over a somewhat shorter time scale – so does oil. It’s by no means a one-way bet.

The big theme of the week was the crisis in shareholder capitalism. There were three articles in the Economist and one in the FT on this – we’ll look at two of them.

John Authers reported that large investors are increasingly taking a more long-term and inclusive view of things.

- He began with the shrinking free float (as a proportion of total market cap) in the S&P 500, due to recent corporate share buy-backs. Around 9% of market cap has been withdrawn since 2011.

- The second driver is that companies are choosing to stay private for longer.

- Third, US endowment funds and public pension funds are making greater use of private equity, presumably because it is easier to impose a long-term perspective.

- A fourth trend is the rise of what John calls ESG (environmental, social and governance) investing – what we used to call ethical investing I guess.

All of these suggest a lack of trust in shareholder market capitalism – the legal requirement for US corporations to “produce [maximum] profits for the stockholders”. Similarly for US pension funds.

The US now has the “benefit corporation”, which commits to creating public benefits, as well as profits. Directors must take into account the interests of all “stakeholders” not just shareholders. There are now 3,000 of these, most created since 2009.

And the US pension regulations have just been relaxed to allow “environmental, social, or other such factors” to be included in investment criteria.

So perhaps things will change. But knowing the history of American capitalism, I wouldn’t bet on it.

The Economist looked at how entrepreneurs are reinventing the company. Like John Authers, the newspaper detects disillusionment with the traditional public company.

Traditional firms have largely anonymous owners – represented by somewhat disengaged fund managers. In contrast, new insurgents are often owned by founders, staff and early backers.

These firms still use talent and capital to come up with innovative products, but the balance between regular reporting (quarterly in the US) and long-term investment has been upset.

Managers now tend to put their own interests first.

- Shareholder value in the 1980s was supposed to make managers think like owners.

- But stock options make them focus on the share price instead (hence all those buy-backs).

The increase in institutional share ownership (now at 70% in the US) has weakened the link to ownership, and regulation has become onerous.

This all becomes more obvious at a time – like today – when corporate profits are being squeezed.

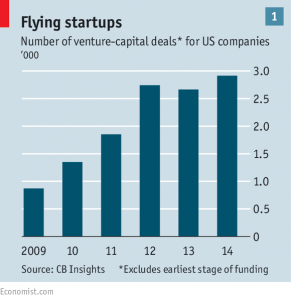

So big startups – the $1bn “unicorns” are flourishing at the moment.

- Ownership is clear, and incentives are truly aligned.

- Most are still privately owned, which means that real KPIs are used instead of accounting ratios.

The Economist describes three objections to this being a revolution we can all support:

- it’s mostly in Silicon Valley, though perhaps Uber and Airbnb can change that perception

- the startups may eventually list on stock markets (“sell out”), though the average age of a company at IPO is up to 11 years, from four in 1999 – and many founders use “A” shares to retain control

- private ownership deprives ordinary people a stake in capitalism, rewarding VCs instead; crowd-funding is not really a substitute

The newspaper expects traditional firms to remain on top in capital-intensive industries, and for many startups to fail. But more will come behind them.

The immigration equation

Tim Harford looked at the costs and benefits of immigration.

I don’t want to go too far down this particular rabbit-hole, but I do want to take issue with his basic point that the positive impacts on the immigrants themselves should be included in the equation.

For the record, I think that letting young, hard-working people into the country is very likely to have a positive effect. I also believe that it’s up to the current inhabitants of a country to decide who they want to let in.

Back to the point. If we are trying to decide whether to add something to a closed system, it’s the effect on the system as it is constituted before the decision that counts.

Tim likes to compare immigration to the NHS and the education system – the benefits to schoolkids and the sick are needed to balance the books.

But those people are already inside the system. Each of us has been, or will be, in their position at some point.

Under Tim’s equation, I have to consider the positive effect on squatters of their invasion of my home whilst I am away on holiday.

And presumably Tim wouldn’t mind if I pop round to “borrow” his car when I need to nip to the shops.

Sharing everything with everyone is dreamland economics. We need to grow the cake so that there is enough for everyone, not share five loaves and two fishes with five thousand people, so that no-one has enough to eat.

Or if you prefer, we have to be careful not to let so many people into the lifeboat that it sinks.

Tax credits

The other political hot potato of the week was tax credits. I didn’t expect the Lords to vote to delay them – since they had been voted on three times by the Commons – and I am sure there will be repercussions.

There’s no doubt that the proposed changes have stirred up a lot of emotion, which I will try to avoid today:

- I think tax credits are a bad thing because they incentivise employers to pay wages that are too low to live on, for jobs that might not really be viable

- I’d like them replaced by a higher minimum wage and a higher personal tax allowance, which is the basic proposal on offer

The objections seem to centre on the idea that working families will lose money as a result. If you accept point one, that seems inevitable.

So the discussion becomes how much should they lose, and over what timescale. Or as the Chancellor now puts it, will “transitional measures” will be needed for the worst affected?

The changes should probably have been synchronised with the National Living Wage from the start.

But the system needs reforming. It costs £30bn a year, and the cuts are just £4.5bn. There were £12bn of welfare cuts in the manifesto, and they have to come from somewhere.

The bigger picture is that these “fake jobs” are likely to disappear in the next decade, replaced by robots and software automation.

If in the mean time we can convert some of them to real jobs we may go some way to solving the UK’s “low productivity puzzle”.

Until next time.