Weekly Roundup, 24th August 2020

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup with a look at the value premium.

Value

Joachim Klement was back from holiday and explained that value is not a risk premium.

- Like a lot of people, Joachim has a problem with the academic definition of risk as volatility of returns.

It was introduced in the 1950s because it was relatively easy to calculate before processing power was cheap, and amongst other things, it conflates upside and downside volatility.

- It used to annoy me, too – but as I get older I find that it’s not a bad proxy for whatever version of risk really drives investor behaviour.

Joachim also has a problem with the idea that there is a risk premium at all.

- This implies that riskier assets should have higher returns.

This is true between asset classes (eg. stocks vs bonds) but often not true within them.

- Low volatility stocks outperform riskier ones.

And as Joachim points out, there’s also a perception problem.

- Most people think that property is safer than stocks, but most people also believe that property has higher returns than stocks.

According to theory (and in this case, also in practice), both of these things can’t be true.

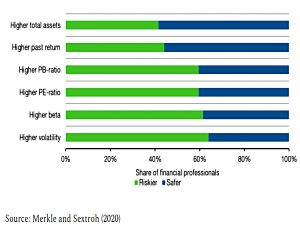

Coming back to stocks, a recent paper asked German financial professionals to classify stocks as risker or safer according to various metrics.

Higher volatility and higher beta were seen as risky.

- Large caps, and value and momentum stocks were seen as safer, which is interesting since momentum and value stocks tend to have opposing characteristics.

It’s also interesting that according to theory, value stocks should outperform because they are riskier.

- But these finance professionals don’t see them as riskier.

- High PE growth stocks are instead seen as risky.

As Joachim puts it, either the theory or the professionals are wrong.

Stocks vs Bonds

Joachim’s second article looked at the performance of stocks and bonds over the last 50 years.

- Bonds have benefited from falling interest rates – a bond with a duration of 10 (years) should gain 10% for every 1% drop in interest rates.

Equities can be seen as bonds with variable coupons (dividends) and a duration which is the inverse of the dividend yield.

- So a stock yielding 3% would have a duration of 33 years (in practice interest rates don’t impact dividends directly, so the duration in shorter).

If we match stock dividends to government bond coupons, we should expect a risk premium on the dividends because they are less dependable than government bond payments.

- Unfortunately, this doesn’t seem to happen in practice.

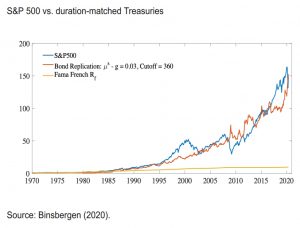

A recent paper compared the SP&P 500 to Treasury coupon strips from 1970 to 2020.

- Bonds had similar returns with lower volatility, for a higher Sharpe ratio.

This means (amongst other things) that a 20-year Treasury is a good diversification match for the S&P 500.

- It reduces short-term volatility without impacting returns, which makes it a better fit than the short duration bonds which are traditionally used.

Basic Income

The Economist reported that universal basic income is gaining momentum in the US.

- We’ve looked at this attractive idea several times before but never found a sensible way of paying for it.

The current resurgence in the US is down to Andrew Yang, who included a $1K per month UBI as part of the manifesto for his run for the Democratic presidential nomination.

- As well as paying for it, UBI faces the additional problem that it sounds very socialist to many American ears.

But support amongst conservatives has risen to 45%.

- Tech gurus who worry that software will eradicate jobs also tend to be in favour.

Perhaps Covid-19 job losses will also give it a boost.

- Or perhaps the experience of the pandemic furlough schemes will convince voters that providing a permanent living wage to those who are not working is too expensive.

There have been lots of UBI experiments in the US and elsewhere, but they are hard to interpret because (i) they are never universal and (ii) they never provide enough income to live on.

- Funding a real UBI remains problematic, and it’s hard to argue against more targeted welfare payments.

The lower bound

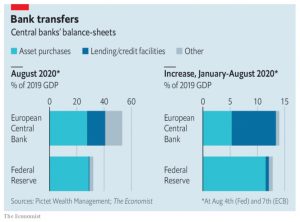

The newspaper also looked at whether the ECB has found a way around the lower bound on interest rates.

- The central bank has been cutting rates in small increments (usually 0.1%) since it knows the limit is near but is not sure where it is.

It has also been bond-buying, and it has decoupled the interest rate on its loans to banks from the main rates.

- Negative rates can’t be passed on to consumers, who will sit on physical cash (with an effective rate of zero) – this squeezes banks’ margins and reduces their willingness to lend.

At a point known as the reversal rate, the impact of a rate cut on banks will outweigh the stimulus to the wider economy.

The more a bank lends to households and businesses, the lower the rate at which it can access TLTRO [targeted long-term repor operations] funds.

Banks can now access funding at -1%, restoring a profitable spread for them.

- The TLTROs have proved popular, and seem to be effective.

There could be political problems ahead since highly negative lending to banks would mean that the central bank loses money.

- It also makes some people think that they are subsidising “greedy bankers”.

Andrew Bailey, the BoE governor, has said that he has no plans to follow the ECB’s lead.

Minimum wage

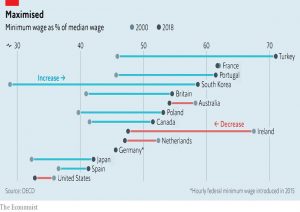

The Economist also had a schools brief on the impact of minimum wages.

- For a long-time, the economic consensus was that minimum wages should increase unemployment amongst the young and the low-skilled.

The logic is that a firm paying a worker more than the value he adds would lose money, so they will do without (or replace the job with automation).

- The degree to which they can do this depends on competition (especially foreign competition not subject to the same minimum wage) and the ease of automation.

Conversely, a firm paying less than the added value would find the worker poached by a company prepared to offer more.

- Thus the least productive are the most vulnerable, and these are the people that the policy is designed to protect.

But data from the patchwork of minimum wage levels and changes between US states has changed this view.

As usual, the issue is that economic reality departs from theory:

- Employers are not sure how much value a worker adds

- Workers do not have access to a variety of jobs paying the wages equivalent to the value they add.

A comparison of fast-food workers in New Jersey (which raised the minimum wage in 1992) and neighbouring Pennsylvania (which didn’t) showed no impact on jobs.

- The most likely explanation is that dominant employers (such as McDonald’s) were exploiting their monopsonic position to page wages below the market-clearing level.

So a higher wage can draw more people back to the labour market.

- And in competitive markets (fast food, groceries) employers will be unable to raise prices and must absorb the cost.

Some studies have shown bigger impacts, and the threat of automation has not gone away.

- But things are not as clear-cut as they seemed 30 years ago.

Stock splits

David Stevenson noted the surprisingly positive impact of the stock splits announced by Apple, and in particular Tesla.

- Stock splits should have no effect on the market cap of a firm, but they usually provide a boost.

The remaining FANGs also have high share prices:

- Amazon (AMZN) $3,284

- Alphabet (GOOGL) $1,555

- Facebook (FB) $264

- Microsoft (MSFT) $210

More interestingly, he noted that a lot of popular ETFs are also highly-priced and might benefit from a split:

- iShares Core S&P 500 $338

- iShares Core US Aggregate Bond $118

- iShares Core MSCI Emerging Markets $52.86

Quick Links

I have a monster fourteen links for you this week.

- I’ve been catching up with my summer backlog of magazines, so the first eight of them are all from the Economist.

- The Economist wrote that Big Tech is the new dividend royalty

- And that IPOs are back in Silicon Valley

- And indeed, that they are being reinvented

- But that Google’s problems are bigger than the anti-trust case

- The newspaper also claimed that emerging economies are catching up

- And that social media made GymShark

- And that the fear of robots displacing workers has returned

- And looked at what a million-mile battery might mean for electric cars

- Forbes looked at Robinhood’s billionaire founders and their links to “Wall Street Sharks”

- UK Value Investor wondered whether Jupiter Asset Management was a good investment

- The Times took a closer look at the Hipgnosis Songs Fund

- Alpha Architect looked at earnings calls, cliches and negative abnormal returns

- And said that even great investments experience massive drawdowns

- And Musings on Markets had another Viral Market Update, in which the strong get stronger.

Until next time.