Weekly Roundup, 5th May 2015

We begin today’s weekly roundup in the FT, with the chart that tells a story.

Contents

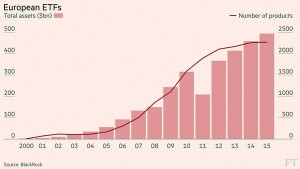

15 years of ETFs

Jonathan Eley and Judith Evans looked at the growth in ETFs, which were launched in Europe fifteen years ago this week. ETFs – as opposed to ETPs – must track a suitable index and follow UCITS rules. The big players are BlackRock (iShares), SG, HSBC, Vanguard, UBS and Deutche Bank.

There are now more than 2000 ETFs on European exchanges and the industry has $500bn of assets under management. Many of the offerings are too small, with insufficient liquidity, so investors need to choose carefully.

Costs have come down nicely, with the original FTSE 100 ETF falling from 0.40% fifteen years ago to 0.07% now. Costs for smaller funds and those covering less mainstream indices remain significantly higher.

Basic income

Having looked last week at radical left-wing proposals to address inequality, this week Tim Harford put forward a hypothetical radical conservative agenda. His first suggestion was to reform welfare along the lines of the Basic Income (BI) proposal we looked at last week, as part of our General Election coverage. ((Basic Income is a long-term commitment from the Green Party))

Tim’s version is to scrap all benefits apart from disability, and also remove the income tax personal allowance. The BI would be £8K, but income tax would be at a flat rate of 40%. That means net BI is only £4.8K, which is nowhere near enough to live on, and doesn’t even replace the new state pension. ((Which will be £8K, and untaxed since it is less than the personal allowance))

Tim would phase in BI over ten years on a residency basis, so that recent immigrants have to pay more into the systems at first. As previously discussed, this targets poverty rather than equality, removes bureaucracy and incentivises everyone to work.

His second proposal covers education. Institutions would compete for tax-sheltered pots of money administered by parents that could only be used for education. Compulsory schooling would end at 14, and more practical training courses would be encouraged. At age 21 any remaining funds are given to the child. His third idea is to scrap pensions and uses Isa-style accounts to save for retirement.

His fourth idea is to build lots of houses quickly, in special zones with lighter planning regulations. He’d like to see 400,000 homes a year for five years. The fifth idea is more taxes: no VAT exemptions, a carbon tax, and more proportionate housing taxes. He would also commit to staying in the EU and not meddling in the NHS.

Apart from the BI being too low, as a set of ideas this is not bad. The difficulty comes in the implementation of so many radical departures from current thinking at the same time. The houses and taxes proposals would be easiest, and pensions have been all but killed off already. ((Via the £1M lifetime allowance, the plans to raise the access age in line with the state pension, and the limits on tax relief for high earners))

The education proposal is very attractive – I despair of the current thinking that upwards of 50% of children should go to university. But more vocational training in a competitive market won’t halt the gradual replacement of people with robots and software. We need to decide what we’re going to do with people whose skills are not needed.

Which brings us full circle to the most radical proposal, BI. I think this is inevitable in some form over the long term, but it remains difficult to see how we get there from here. Still, credit to Tim for including it in his wish list.

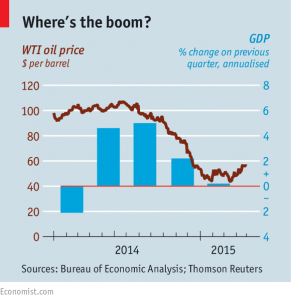

No oil boom

The Economist reported on the smaller than expected economic boost from lower oil prices. The US in particular, with twice the per capita consumption of Britain or Japan, was expected to benefit. But in fact the economy slowed.

GDP is made up of four components:

- government spending

- net exports (ie. exports minus imports)

- consumer spending

- investment

The oil price crash has definitely helped exports, as the US imports a lot of oil. An annual $200bn has been saved here. Consumers have also received a windfall from lower prices, but low wage growth means they are reluctant to spend, and there has been no boost here.

Government spending has not been greatly impacted either. Which leaves investment. Here the reduction in domestic oil production has has a negative impact, cutting GDP by 0.8%.

The good news is that (for the first year at least) the falling oil price pushed down inflation, which means that interest rates could be kept low. This should help the economy in the long term, but the effect is now at an end. After almost a year of falling oil prices, there is little benefit to show for it.

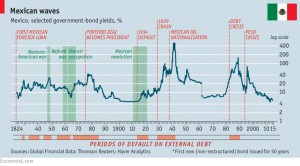

100 year Mexican bonds

The newspaper also reported on an event that passed me by – the issuance in early April of 100-year Euro bonds by Mexico. Buying this bond requires the investor to believe that:

- the Euro will still exist in 100 years,

- that Mexico will remain creditworthy,

- and that some other asset will replace the then-exhausted Mexican oil as a basis for repayment.

And yet $5bn of these 100-year bonds have been sold in the past five years, in dollars, sterling and now euros. The main buyers are insurance companies and annuity firms, who also like the longevity.

Yields vary from 6.1% on the dollar bonds down to 4.2% on the recent Euro bonds. This does compare favourably with the negative rates available from the likes of Switzerland, but still.

The Mexican economy has long-standing problems. Despite booming exports (mainly cars) to the US, per capita output has grown at only 1% pa. Wages are low and poverty levels stagnant, with no boom in domestic demand. Demographics are more positive, with 46% of the population under 25.

No tech bubble yet

Buttonwood maintained that tech stocks are not in a bubble. Like the FTSE-100, the NASDAQ has just passed it’s 15-year-old all time high, when it traded on a PE of 150.

This time the PE is only 26, and the progress back to the high has been more linear than exponential. Tech stocks make up 20% of the US market, rather than the 30% they comprised in 2000.

Biotech is booming (up 50% in a year) but this is on the back of some blockbuster drugs (eg. Gilead’s Sovaldi treatment for hepatitis C). No need to worry just yet, but watch this space.

MaxMyInterest

The newspaper also reported on MaxMyInterest, a 1-yr old service in the US that moves money between banks in search of higher interest rates. At the same time, it keeps balance below the federally insured level of $250K.

Average interest on US deposits is 0.09%, but MaxMyInterest can boost this to between 0.75% and 1.05%. This may not amount to much in dollar terms at present, but could be significant when / if interest rates rise. Something to look out for over here.

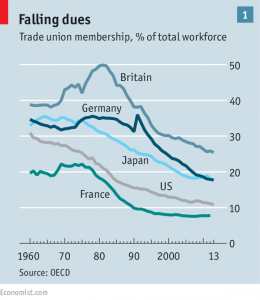

Low wages

The newspaper also had an excellent briefing on low pay. Politicians on both sides of the Atlantic are starting to get behind the idea that stingy bosses are keeping wages down even as economies recover. Certainly wages remain low – in Britain real median pay in 2014 was 10% below a 2008 high.

Beyond those directly affected, this matters because workers are shoppers, and those with low wages won’t consume as much. Or if they do, they will fuel it through unsustainable borrowing.

The problem pre-dates the recession. Productivity and wages moved in tandem between 1947 and 1960, but not since. In the US, productivity is up 220% since 1960, but wages are only up by 100%. Labour’s share of GDP is falling, and becoming increasingly skewed towards those on higher wages.

There are several reasons for this:

- returns on capital, and in particular housing, are increasing

- machinery offers better value for money (lower real prices, or increased output)

- globalisation affects rich country wages

- the decline of unions has reduced labour’s bargaining power

What seems to have changed is the role of unemployment. The theory is that once unemployment is low, remaining workers are scarce and can bid wages up. The key level is the catchily-named NAIRU. ((Non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment))

Generally after a recession the NAIRU would rise, as some workers now have outdated skills or are depressed. Wage inflation should happen sooner, but that’s not the case this time. Unemployment in Britain was below the estimated NAIRU of 6.9% throughout 2014 but real wages declined by 0.6%.

They have now finally started to rise in 2015, though this may be due to record low (zero) inflation. Zero hours contracts make it easier to raise labour without raising wages, and increased use of temporary and agency workers is also a factor.

More regulation is not the answer. France has the most rigid regulations in the G7, and a 10% unemployment rate. The country has created 140K jobs since 2010, compared to 1.6M in flexible Britain. Low-paid jobs are better than none.

Tax cuts – like the personal allowance increases in Britain – help everyone, and so are expensive. Focussed tax credits for the low paid merely help to keep wages low.

The third option is higher minimum wages. This is risky as it could reduce demand for workers if set too high. The comparison with investment in machinery (or increasingly, in software and robotics) becomes less attractive.

There are no easy answers here.

Until next time.