Weekly Roundup, 1st September 2020

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup in the FT, with lumber prices.

Contents

Lumber

In the FT, Harry Dempsey wrote that lumber is on course to be the year’s best-performing commodity.

- Wood is up 104% to date – more than four times as much as gold – to its highest price on record.

The price increase is a combination of mills (especially in North America) reducing production in expectation of lower demand in a recession, and a home renovation boom driven by furlough payments.

I have personal experience of this, having built a deck and several pieces of garden furniture over the summer.

- Not only is wood much more expensive than I remembered from the last time I did this, but it’s also quite hard to get hold of.

Most items are on lead times of several weeks, and no single store has all the sizes and types that new need. (( Deck screws were the hardest things to find ))

Algorithms

Tim Harford looked at the dangers of using algorithms for life-changing decisions.

- The article was prompted by the row over UK exam grades.

Tim is left-wing, so he sees the affair as a shambles. (( ie. an opportunity to have a go at the government ))

- But without going too deeply into the politics of the situation, using algorithms to solve this kind of problem (lots of people competing for limited resources) seems in principle very plausible to me.

There are two possible objections:

- Was it the right algorithm?

- Should algorithms be used for one-off decisions which have a big potential future impact (in this case, which university you get into and whether you get to one at all)?

The first thing to get across is that algorithms are better than human judgement.

- Teachers have biases, conscious and unconscious and with projects of this scale, not all of the pupils can be reviewed by the same judging panel.

- All teachers, like all parents, think that their students/children are better than they really are.

The second is that the perceived weakness of the algorithm – that pupils were judged in the context of their school’s track record – is nothing new.

- Universities have been doing this for decades, if not centuries. (( More than 40 years ago, I was assessed by Cambridge as having no chance of achieving the grades forecast by my school, since my school had never sent anyone to Oxbridge. Of course, I got the grades, but I had to take what would have been a gap year for a middle-class student but in my case was a year at home on the dole, and then had to get into Cambridge via the seventh-term entrance exam ))

It’s true that the exemption of niche subjects (with small sample sizes) from the algorithm will have favoured private schools, but as far as I know, state schools are not forbidden to teach such subjects.

The third point is that although no algorithm can give students the grades they would have got in exams they never sat, neither can any other solution, including the one now being used.

- The subsequent U-turn (reversion to teacher predictions) means that too many students have qualified for the available university places.

Algorithms work best where there are many trials, and the accuracy of each trial is not crucial.

- So rules-based stock-picking – and investing in general – works just fine.

They are less good at helping you choose between two houses, or in deciding whether to marry a person – one-off decisions where accuracy is crucial.

In these cases, we can fall back on a coin-toss.

- You need not be bound by its outcome, but when the coin is in the air, you will suddenly understand which way you want it to fall.

Disinvestment from China

John Authers wrote about the letter from the US State Department to US universities telling them that it would be “prudent” to disinvest from Chinese stocks.

- More stringent listing standards are planned in the US, and a lot of Chinese firms are likely to delist by the end of 2021.

The US administration also has one-to-one battles with Huwaei, Tencent (WeChat) and TikTok.

As well as the government, China is also unpopular with students, both liberal (human rights issues ) and conservative (offshoring of manufacturing jobs).

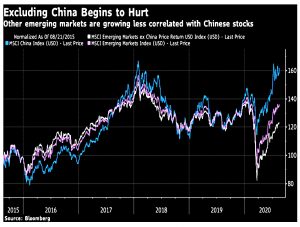

The problem is that China is no longer so well-correlated with the rest of the EMs, and so ignoring it means that portfolios lose some diversification (and gain some volatility).

- China also drives demand for industrial metals, and for steel and coal – industries which the US government is keen to support.

An alternative approach for endowments is to substitute with developed-market companies which have significant exposure to China (eg. Apple, Nike, Qualcomm).

Fed changes direction

Jerome Powell revealed a (slightly) different approach to Fed policy last week.

- Instead of targeting exactly 2% inflation, the rate will be allowed to overshoot after a period of undershooting.

This is a looser strategy and will delay the introduction of higher interest rates to combat higher inflation – which is good for stocks (and bonds).

- Of course, this is all academic if the inflation can’t be generated in the first place.

Demographics, dematerialisation (the internet), globalisation and a move to low-paying service jobs which don’t drive wage inflation are all forces pushing in the opposite direction.

Inflation and the 1%

Joachim Klement also looked at inflation.

- Back in 2008, he (like me) expected money printing to lead to inflation.

He no longer believes this, and I am far less convinced, though I am hoping for asset price support as a minimum.

Joachim wanted to know what hypothetical inflation might do to inequality.

- The consensus is that is should increase since real assets will rise with inflation, whilst low wages and benefits might not.

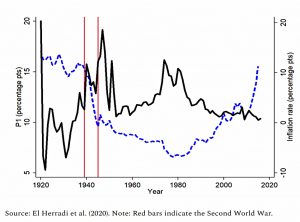

But in fact, inflation hurts the rich.

- Higher inflation means higher interest rates, which means higher discount rates for future cash flows.

So when inflation gets above 4% to 5% pa, stock valuations start to go down, even though the future income is predicted to rise.

- These high rates of inflation signal a future recession and much higher interest rates.

The chart below shows the relationship between inflation and the share of the wealth of the top 1%.

Inflation and unemployment

The Economist had a schools’ brief on why the Phillips curve – which says that low unemployment should lead to higher inflation – has become flat.

When unemployment [is] low, workers will demand pay raises over and above inflation and any improvement in their productivity. If firms pass these higher wages on to customers by increasing prices, inflation will rise.

To combat this, central banks raise interest rates to slow the economy (and the demand for labour).

- At the other end of the curve, high unemployment dampens wages and spending, and hence inflation – so banks will cut interest rates.

Central banks usually target 2% pa inflation, but as we have seen above, inflation has undershot in most countries in recent years.

- Even as unemployment fell after the 2008 crisis, inflation did not rise.

This was the reverse of the situation in the 1970s when high inflation persisted despite high unemployment.

- It seems that worker expectations of inflation – which drive the pay rises they demand – are important.

Imports are also a factor since unemployment in a country will not affect wages abroad.

- Cheap imports from China will depress inflation in some sectors.

The current flat curve could mean that the amount of spare capacity in the economy is being misreported.

- When unemployment is very low, those on the margins of the labour force (usually women and older men not counted as unemployed) are tempted to rejoin.

There is also some evidence that the Phillips curve still works as normal in local markets (eg. US cities) but disappears when aggregated at a national level.

And there is a lower bound problem – central banks find it hard to cut rates below zero since people hold their cash outside of banks.

- The Fed could not get rates above 2.5% in the last cycle – perhaps because of a “global savings glut” – which left little room for cuts when Covid-19 struck.

This is leading central banks and governments to work more closely together once again, after an extended period of central bank independence.

- The idea is that governments are willing spenders of the “limitless” money created by the banks.

Let’s hope this new experiment works.

Bubble hunting

The Economist also reported that bubble hunting has become more art than science.

- The usual gauges are not working, so investors must rely on behavioural signals.

As Covid hits earnings, but share prices are supported by the actions of the Fed and other policy bodies, PE, free cash flow and ROCE stop working.

- So we have the S&P 500 at an all-time high during probably the worst downturn for 90 years.

Some of the froth in particular stocks may be down to new retail investors (the Robinhood effect, though the newspaper also mentions r/wallstreetbets on Reddit).

- We also have a lot of shares being issued – largely to recapitalise firms hit by Covid, but also tech IPOs and special-purpose acquisition companies (SPACs).

The last are listed shell companies designed to merge with private companies to bring them quickly to market.

Meanwhile, Buffett has sold banks and bought gold (trending) and Japan (good value).

- The newspaper offers no guidance on what the retail investor should do.

Quick Links

I have just four for you this week, all from the Economist:

- The newspaper wrote about the Palantir IPO

- And the Ant Group IPO

- And the impact of the Beirut explosion on insurers

- And described how Covid-19 has been a mixed blessing for makers of medical equipment.

Until next time.

Interesting to see that the press coverage of the, so-called, exams fiasco is moving towards what I consider to be the real issue – why were the exams cancelled.

I understand that other parts of Europe did them suitably socially distanced. Maybe this is just the start of the Brexit bonus.

Having said that, I suspect it will take a few more years before the consequences of some of the pandemic decision making become apparent – by which time peoples attention will have probably [been] moved on to something else anyway.

Interesting aside about your Cambridge entrance experience.

IMO, Bojo is an appalling advert for the value of an Oxbridge education – “mutant algorithms” , I ask you!

I think Boris was at Oxford, and read PPE or Classics or something. One of the many problems with this country is that we take arts graduates too seriously.