Weekly Roundup, 4th August 2015

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup with the FT, and a landmark ruling about wills.

Contents

Will overruled

Claer Barratt reported on a controversial Court of Appeal verdict which reinstated a woman written out of her mother’s will. The daughter was awarded £163K from a £500K estate that had previously been heading for animal charities.

The appeal was made under the “reasonable financial provision for the maintenance of a child” section of the 1975 Inheritance Act. I’m pretty sure this was intended to look after kids under 18, but it’s increasingly being applied to adult children.

With the increasingly unequal distribution of wealth between the generations, more adult children are likely to dispute their parents’ wills.

The judge ruled that the mother had acted in an “unreasonable, capricious and harsh way towards her only child”. The low income, lack of pension and reliance on benefits of the daughter were all significant factors in the verdict.

The animal charities were held to be well-funded regardless of the bequest, and the mother had no previous connection to them.

Pension freedoms

Don Ezra looked at the withdrawals from pension pots in the early months of the new access freedoms. More than £1.8bn was withdrawn in the first two months, and a quarter of that was used to buy cars and holidays.

It’s probably too early to read too much into this, as at the start of any new freedom, there will be a “big bang” effect from pent-up demand. ((Many pensioners seem not to have been granted easy access, and so it’s possible that some demand is still pent-up))

There are two schools of thought:

- people will take out too much and run out of money (the Australian pattern)

- Australians have had a lump-sum pension for a long time, and many retirees have spent their lump-sum too quickly

- the system was changed in 2007 to favour a series of regular, smaller withdrawals

- people know how to manage their finances and everything will be fine (the Canadian pattern)

- Canadians live on much less in retirement than in pre-retirement, and often don’t spend as much as they could from their pensions, with no impact on their happiness

The very fact that two quite similar countries have had very different experiences means that the future is hard to call.

Don looked at the human brain to explain both options:

- “hyperbolic discounting” means that we pay more attention to the present than to the future

- present needs dominate future needs, and emotions dominate rational assessments in the short-term

- this explains the Australian experience

- dopamine decline over age means that old people are less driven than young people, and therefore demand fewer goods and experiences

- this means that spending should decline through retirement, making pension pots last better than expected

- people change fromoptimisers who demand perfection to “satisficers” who think that “pretty good is enough”

- this again puts downward pressure on spending over time

- it also explains the U-curve of happiness: older people are happier because they are more prepared to settle for what life offers them

- these last two points explain the Canadian experience

Don also points out that with the new state pension at around £16K for a couple, most of the minority who blow their pots won’t need (or receive) further help from the state in any case.

Alternative assets for income

Judith Evans looked at the alternative assets that are turning up in multi-asset income funds. They include:

- a caravan park in Cornwall

- other specialist property (student accommodation, medical centres, garage forecourts)

- hurricane insurance in Florida (via Blue Capital Reinsurance, which yields 6%)

- renewable power generation contracts

- personal loans

- aircraft leases

- timber

With yields on deposits and bonds at record lows, asset managers are looking at asset classes once deemed too long-term, illiquid or risky for retail investors. Investment in these assets rose by 11% in the year to February 2015.

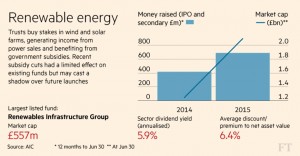

Renewable energy investment trusts (such as Greencoat UK Wind and Bluefield Solar Income) have grown from zero in 2012 to a market capitalisation of more than £2bn today. The government has now cut subsidies to many of these projects, so future growth may be less spectacular.

Infrastructure investment trusts – which finance long-term projects such as roads, schools, airports and energy grids, usually with some form of public sector funding – now trade at an average premium of 13.7%.

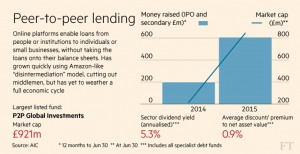

The first P2P loans investment trust launched in May 2014, and the sector now has a market cap of £1.2bn. P2P Global Investments (LON:P2P) buys loans through platforms like Zopa and Funding Circle.

P2P is targeting a 6% to 8% yield, through the use of leverage. Neil Woodford is one of the biggest holders.

I’m not convinced that this move is a big deal. A low exposure to most of these assets is worth considering, though many are now quite expensive.

Multi-asset funds generally have regulator limits on the proportion of exotic assets they can hold, so a widespread collapse is not likely.

More probable is a gradual (or possibly a sudden) move away from these “bond proxies” when interest rates eventually rise.

Rising wages

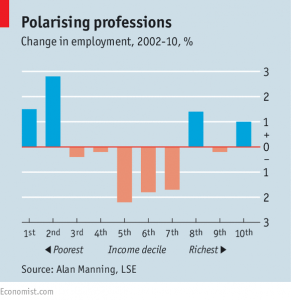

The Economist looked at where jobs might be lost as a result of rising wages. Since the 2008 financial crisis, wages have stayed low, but the number of low-paid (and high-paid) jobs has been increasing relative to those in the middle.

But real wages rose by 2.7% in the three months to April, and the budget announced a 38% rise in the minimum wage (now the “new living wage”) over the next five years.

This will cause problems in labour intensive sectors like hospitality and tourism. The new auto-enrolment workplace pension scheme is also an issue, as is the lack of a VAT rebate for these sectors, as is common in Europe. More jobs for those under 25 are likely, since they are exempt from the living wage.

Residential care is another area where jobs will go, as increased cannot be passed on to their local authority customers, whose funding has been cut. As staffing levels are regulated, whole services will have to close. Corner and village shops also face problems.

But in areas where people cannot be replaced by machines (eg. hotel cleaners, nurses) fewer jobs will go.

Routine jobs in administration or manufacturing make better targets for automation, and often pay better. More hollowing out or “job polarisation” seems likely

ETFs and hedge funds

The newspaper also had two pieces about the overtaking of hedge funds by ETFs, and the poor returns that hedge funds offer . In 1999 ETFs held only 10% of the money that hedge funds controlled, by now they have more than 100%.

While hedge funds often claim genius and excess returns – along with a 2% annual fee and 20% of upside performance – ETFs simply promise average returns at a low cost.

There’s still too much money in hedge funds though – their recent performance can’t justify the high fees. Low return markets don’t suit high cost funds like hedge funds. Since the 2008 crises their average return is close to that of a 50/50 bond – equity split portfolio.

After the crisis, the industry stopped targeting individuals, and went after institutions like pension funds and university endowments. Diversification and low short-term volatility are now pushed rather than the earlier excess returns.

It’s not clear which this would suit pension funds, whose liabilities are long-term – property or private equity would be better.

And there aren’t really enough hedge funds to go around – $3 trn compared with $36 trn in pension funds around the world. Even if a pension scheme grabbed 10% of hedge funds, a 2% outperformance would add only 0.2% to their bottom line.

Some big US funds (eg. CalPERS) have said as much, but others are looking to hedgies to get them out of the hole caused by their unrealistic return assumptions (often 7.5% pa or more, when Treasuries yield around 2%).

Commodities and emerging markets

Buttonwood looked at falling prices in commodities and emerging market equities.

Five years ago this seemed unlikely. Emerging markets were expected to surge ahead, driving demand for raw materials and the global “commodity supercycle”.

Commodity prices are now down 40% from the peak in 2011. This is not seen as a great problem from the West, where most countries are net importers.

But it hurts commodity exporters, many of which are emerging markets. Of the old BRICs, only India is still accelerating. China is slowing, and Brazil and Russia are actually shrinking.

It’s the China slow down that most impacts demand for commodities, and hence their price. There’s also been a switch from assembly of foreign components into manufacturing from scratch. Global supply of shale oil and gas has also increased.

Are there any implications for the global economy? Would a US interest rate rise this year be premature?

The IMF forecast for 2015 global growth is 3.3%, down from 3.4% in 2014. But that would still be the worst year since 2009.

Higher US rates will help the dollar, impacting monetary policy for those countries tied to the currency, and creating problems for those with lots of dollar debt.

Perhaps the rate rise could wait a while.

Return forecasts

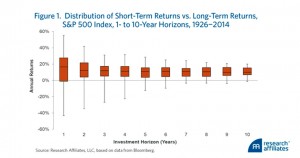

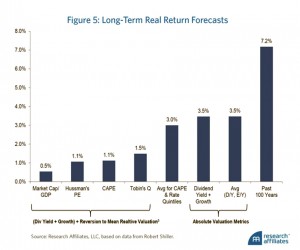

Over in Money Week, Cris Sholto Heaton looked at a report from Research Affiliates which used seven different valuation models to forecast the expected return from the S&P 500 over the next 10 years. Chris Brightman, Jim Masturzo and Noah Beck began by baselining the distribution of returns over the past 88 years.

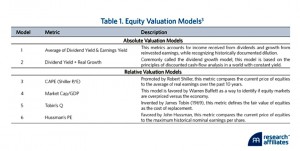

Next they identified the most commonly used valuation methods.

And finally they calculated the likely returns using each of the models. The returns vary from 0.5% pa up t0 3.5% pa, but they are all a lot less than the historic average of 7.2% pa.

The models can be divided into two groups:

- The two on the right of the graph are based on current earnings, dividends and valuations.

- They assume that current levels of all these values are typical, and that investors will earn a steady return from dividends and from growth fuelled by reinvested earnings

- When the values are not typical – say earnings or valuations are high – they will forecast too high

- The four on the left are based on relative valuations.

- They compare the current value of the stock market to some other financial metric and that ratio to its long-term average.

- These models should be better at identifying overvalued stocks and potential capital losses as valuations return to normal levels.

- All of them suggest that’s likely now – US stocks are apparently expensive.

The main problem with the relative valuations is that the relationships between metrics might change over time.

- The obvious example is the ratio of market cap to GDP – this varies between countries at the moment, and there’s no particular reason why it should remain constant over time. Countries and historical periods with a culture of equity ownership and tax breaks supporting the structure might be expected to have larger stock markets.

- That said, it might be a good idea to take note of extreme values in a ratio like this, since they may predict that a period of reversion to the mean is about to start.

- There are similar problems with the Cape measure. Using a ten-year average for inflation-adjusted earnings is supposed to cope with fluctuations caused by the economic cycle.

- The S&P 500 Cape is currently 27, which is 75% above its average for the past 144 years.

- But changes in accounting standards, tax rules and business approaches to spending and investment mean that earnings today might differ greatly from those of the past; the sector composition of the index will also have changed significantly.

- We look last month at Jeremy Siegel’s critique of the Cape – mark-to-market accounting has greatly increased the volatility of earnings since the 1990s; earnings in 2008 dropped more than in the Depression, a slump in GDP that was five times bigger.

- Siegel argues that ignoring the increased volatility means the Cape is always high, and always predicting low returns in the future (returns have beaten the Cape prediction in all but six months since 1981); even in May 2009 the market appear overvalued, but it has more than doubled since then

A second problem is that external economic factors (inflation, GDP growth) affect how much investors will pay for stocks. Low inflation and good growth (as at present) means high prices. So the reversion to the mean may not happen until inflation increases or growth stalls.

- Research Affiliates calculated that when real interest rates were low, as they are now, returns averaged 3.0% even when the Cape was as unusually high as today.

They further calculated that both the dividend-based model and the Cape-based model could explain only around 30% of subsequent ten-year returns, making them poor measures on which to base a strategy.

So it’s likely that returns will be lower than many expect, and that US stocks are expensive relative to the rest of the world, but that’s probably as far as we can go.

Until next time.