Weekly Roundup, 6th April 2020

Today’s Weekly Roundup is once again mostly about the coronavirus and its impact on the markets.

Contents

The Oxford study

Tim Harford explained why we shouldn’t rush to believe the somewhat comforting Oxford study of the virus spread.

- This supports the “tip-of-the-iceberg hypothesis” which suggests that most infections are undetected due to limited testing and lack of symptoms.

This would mean that lockdowns – whilst still necessary to avoid overwhelming ICUs – could soon be lifted.

We have good numbers only on deaths, and they are consistent with more than one scenario:

- Rare and deadly

- Common and not lethal to many

John Ioannidis, who 15 years ago wrote “Why Most Published Research Findings Are False”, says that the fatality rate could be anywhere between 1% and 0.05% (regular flu has a death rate of 0.1%).

- He says that Covid-19 “might be a one-in-a-century evidence fiasco”.

Tim says that decent testing on evacuees from Wuhan city and the Italian town of Vo show that more like 50% of cases are asymptomatic.

- I think testing in Iceland came to similar conclusions.

Which means we are nowhere near herd immunity in the UK.

- Testing for antibodies will have the biggest impact, allowing the now-immune to return to work.

Investment trust discounts

Madison Derbyshire reported that UK investment trusts at are now at their steepest discounts since the 2008 financial crisis.

- The average discount is now 22%, down 16% in the week to 24th March and down from 1.1% at the start of the year.

Property funds holding leisure, student accommodation and retail assets were hardest hit. Other poor performers included trusts invested in private equity and private debt. UK small-cap has also underperformed.

Dividend drought

Madison also noted that £3.5 bn worth of dividend payments were cancelled in the week to 27th March.

- This is once again the biggest drop since the 2008 crisis.

High street retailers, pubs groups, property companies, car dealerships, travel companies and UK housebuilders were amongst the firms making cuts.

- This raises questions around whether investment trusts will be able to maintain their “dividend hero” status.

Housing market on hold

James Pickford (amongst others) wrote that the government has effectively suspended the property market.

- They have banned the marketing of new homes and visits to those already listed.

Banks are behind the move, as they don’t want to make loans when prices might be rapidly falling.

- And surveys had become impossible.

The government said:

You can speak to estate agents over the phone and they will be able to give you general advice about the local property market and handle certain matters remotely but they will not be able to start actively marketing your home in the usual manner.

Lloyds will now only offer mortgages to those with at least a 40% deposit/existing equity stake.

- Barclays has the same policy for new loans but is offering remortgaging deals as normal.

Fiscal boost

The Economist looked at just how much fiscal stimulus rich countries were providing in order to counter the effects of the lockdowns and at whether it would prove to be temporary.

In a standard recession firms are allowed to go bust and people to become unemployed. Now governments hope to stop this from happening entirely.

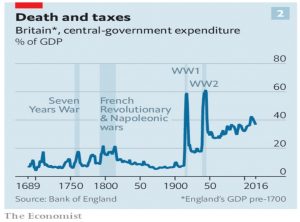

UK government expenditure was already close to peacetime highs before the crisis.

In the 1600s the outlays of the entire English state accounted for about 5% of GDP, with practically no spending on public health or education. That began to change in the 18th century, and from the end of the 19th century Britain and other capitalist countries saw increased state intervention.

Governments may intend to boost spending only for a short while. But then expectations change, making such expansionism hard to undo. It is now common sense that the state should provide education to children at no cost to parents, or support people who are out of work.

While it is easy to ratchet state spending up, it is much harder to push it down. Nothing has helped boost state power in Europe and America more than crises.

And what about after the virus passes?

Over the next year government debt will rise sharply, as spending jumps and tax revenues collapse. When the economy recovers, attention will turn to paying it down. After the first and second world wars many governments in the West turned to heavier taxation of the incomes and wealth of the richest to achieve that goal.

Another option is “financial repression”, where governments force citizens to lend to them at below-market rates.

The real problem will be convincing anyone of the need to rebalance the books.

- It’s much harder to argue that the “magic money tree” doesn’t exist when you’ve been relying on it for the past six months.

Best in show

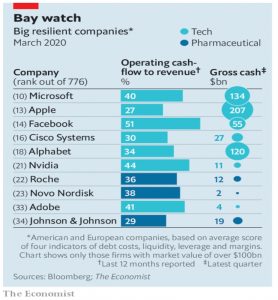

The Economist also argued that the pandemic will make already big and powerful firms even stronger.

Already some are a source of financial stability. It costs less to insure Johnson & Johnson’s debt against default than Canada’s. Apple’s gross cash pile of $207bn exceeds most countries’ fiscal stimulus.

In the long run the top dogs may win market share by investing more heavily than, or buying, enfeebled rivals. In the past three recessions the share prices of American firms in the top quartile of each of ten sectors rose by 6% on average, while those in the bottom quartile fell by 44%.

The newspaper analysed the top 800 US and European firms on four measures:

- the cost of insuring their debt against default

- operating margins

- cash buffers

- and leverage

Unfortunately, they haven’t made this analysis available.

- Not surprisingly, the winners (whose share prices have fallen less) tend to be bigger.

- Tech and pharma firms dominate.

The key risk is that a new social contract emerges after the virus, with companies expected to provide key products for less and offer better support to their workers.

Familiarity impacts performance

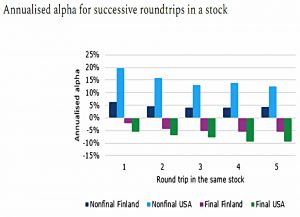

Joachim Klement explained that the more you know a stock the worse your performance gets.

- Most people have a home bias to their own country, and also to the industries that they know best.

This leads to a lack of diversification, but perhaps the additional knowledge can compensate.

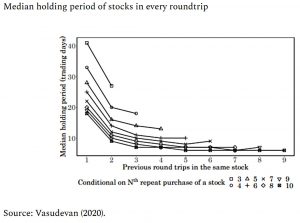

Ellapulli Vasudevan looked at the portfolios of 308,000 Finnish investors between 1995 and 2014 as well as 76,000 US investors between 1991 and 1996.

40% of investors sold out of a stock only to buy it back again, and 10% did this at least six times.

- As you would expect, they found it easy to sell when the stock was showing a gain than when it was showing a loss (which is the opposite of what you should do).

Having sold the stock once, investors seem to watch their basket more closely and sell out more quickly the next time.

- Which makes them more susceptible to short-term noise and hence to underperformance.

At some point, investors have a very bad round trip and they never buy that stock again.

The more often you check your investments, the more you will see short-term noise and react to it.

By watching that basket closely, the investor has accidentally broken one egg, after which that egg gets discarded and the investor focuses on the remaining eggs. Until one of these breaks, etc.

Quick links

I have seven for you this week:

- Verdad looked at the distress anomaly

- Musings on Markets had part 5 of his Viral Market Meltdown series

- Howard Marks asked Which Way Now?

- Alpha Architect looked at Pandemics and Factor Investing

- And at Volatility expectations and returns

- Factor Research reported on the factor returns for 1Q2020

- And Flirting With Models looked at the possible shapes of recovery.

Until next time.