Weekly Roundup, 18th July 2017

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup in the FT, where Robin Wrigglesworth explained the Fed’s plans to trim its balance sheet.

Contents

Fed unwinding

The Fed held a meeting last week with all the other central banks to discuss their plans.

- The current approach is to cut the balance sheet by $6bn a month in Treasuries (by not re-issuing maturing bonds).

- This will increase by $6bn at three-month intervals until it reaches $30bn a month next year.

A parallel reduction in mortgage-backed securities will start at $4bn a month and rise to $20bn a month.

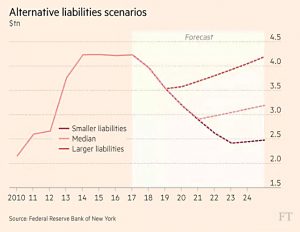

This plan is expected to shrink the balance sheet from the current $4.5 trn down to $3.2 trn.

- But more and less aggressive scenarios target $2.5 trn to $4.2 trn.

- The timescales for “normalization” run from 2020 to 2023.

It remains to be seen how the markets will react.

- Back in 2013, a hint from the Fed that it would scale back its bond-buying led to the “Taper tantrum”.

Jamie Dimon of JP Morgan (( Disclosure – I used to work there )) said:

We’ve never had QE like this before, we’ve never had unwinding like this before.

It could be a little more disruptive than people think.

Corporate debt

In the Economist, Schumpeter looked at the balance sheets of US companies.

- US firms are hoarding $2 trn of cash, but have borrowed $8.4 trn.

- Half of the cash is hoarded offshore, to avoid taxes on repatriation.

Over the past decade, S&P 500 firms have:

- grown debt by 114%

- grown cash by 162%

- grown profits by 51%

Schumpeter thinks that the key ratio is between net debt (debt less cash) and profits.

- This works out at 1.5 times profits, slightly higher than 10 years ago, but lower than in Europe.

Schumpeter infers that companies don’t trust the banks as they did before the 2008 crisis, and they also expect their increased profits (from reduced competition) to continue indefinitely.

- The first position is reasonable, the second less so.

- Anti-trust measures against telecoms, media and internet firms are a particular risk.

Killing Zombies

Buttonwood looked at how to kill a corporate zombie.

- He thinks this may be the key to improving productivity.

- Which is important because ageing demographics mean that productivity has to carry the burden of future growth.

The theory is that zombies – firms that struggle on despite poor results – are what drive down average productivity.

- And the allocation of capital and labour to these underperformers diverts it away from better firms.

Buttonwood uses a definition of a zombie as a company whose earnings before tax don’t cover its interest payments.

- The Bank of International Settlements found that across 14 countries, 10.5% of firms were zombies in 2015, up from 6% in 2007.

A new OECD paper suggests that making insolvency easier would lead to capital being reallocated more quickly.

- And the UK had the best system out of the 35 studied (though it still has low productivity).

Greece, Italy and Spain had 28%, 19% and 16% of their capital tied up in zombies.

Big Mac index

The Economist also published it’s latest update to the Big Mac index, its PPP measure of exchange rates based around a McDonalds burger.

- The dollar has slipped over the past six months, but still looks expensive.

The yen is 37% undervalued against the dollar.

- 32 of the 34 currencies that are monitored are undervalued.

- Only Switzerland, Norway and Sweden come out ahead.

Climate change economics

The newspaper also argued that because the effects of climate change are not distributed evenly, its costs are understated.

Working out the economic impacts of climate change is not easy.

- You need to estimate how temperature changes will affect local weather,

- How weather changes will affect crops and human mortality,

- The impacts on local, and then regional, national and global GDP.

A new study looked at the impact of 29,000 scenarios on US counties.

- Even a 1.5°C rise in global temperature would hit GDP by 0% to 1.7%

- A 4.0°C rise would have a 1.5% to 5.6% impact.

And these effects would not be evenly distributed.

- Some counties might gain 10% while other lost 20%.

- And the poorest areas would fare worst.

The same is true at a global scale.

- The worst effects occur in poor countries and therefore have a small impact on global GDP.

The authors envisage mitigating the effects – within and across countries – through mass migration.

- The current experience in Europe suggests that might be wishful thinking.

Shorters

Last week was a good one for shorters.

- Carillion, the most shorted stock on the London exchange, fell by by more than 70%.

- That’s a lot for a FTSE-250 stock.

It sounds like a recipe for profit.

- MoneyWeek, for example, list the ten most shorted stocks in every issue.

And I think you can get the same information directly from the LSE.

- For what it’s worth, retail and oil seem to be the unloved sectors at the moment.

But Carillion had been on that list for a long time.

- By the time it reached the top, 25% of its shares had been borrowed so that they could be shorted. (( In practice, only larger investors short stocks this way – mere mortals use spread betting ))

Always remember that shorting is risky, because you have unlimited potential losses if the market moves against you.

- On a heavily shorted stock, only a small amount of positive news can lead to a “short squeeze”, where the shorters have to buy back stock to cover their positions.

- This in turn sends the share price higher.

This happened last week with Premier Oil, which announced a big find off Mexico.

- The shares went up 35%, which would be painful for shorters.

Growth

On Twitter last week, Branko Milanovic had a disagreement with Kate Raworth.

She wanted the OECD to change its objectives from economic growth to the creation of

Redistributive and regenerative economies … whether or not they grow.

On his blog, Branko explained why:

De-emphasizing growth is not desirable, and perhaps more importantly, is utterly unrealizable.

Like me, Branko believes that growth is what reduces poverty.

But in addition to that, he believes that capitalism is based on two things:

- greed at the individual level (the desire for more)

- competition at the collective level (as the means to achieve more)

These are not the most attractive characteristics, and they lead to increasing commoditisation over time, but they are the engine of capitalism.

- Everything (free time, networking, Airbnb, Uber) becomes judged in terms of increasing income.

- We want to climb the hierarchy, and that is based around income and wealth.

Branko uses the example of Italy – which has:

High wealth, peace, moderate working hours, strong family and friendship bonds, nice weather, beautiful historical and natural sights, excellent and healthy food.

If any country doesn’t need to grow, it’s Italy.

- And so it has not, since 1999.

- Its per capita GDP was 3.5 times the global average, and now it is 2.5 times.

Yet:

The young are not happy because of lack of opportunities, the middle-aged people are not happy by non-challenging jobs, the old are not happy because their pensions are stagnant.

Even in Arcadia, you need growth.

Aramco

The FCA has come up with a fudge to allow Aramco, the Saudi state-owned oil firm, to list in London.

- Aramco will come with a huge valuation, and the Saudis only wanted to sell 5% of the shares.

- The LSE has a minimum requirement that 25% of shares need to be sold.

So the FCA has invented a new type of listing.

- The “premium listing” will be restricted to sovereign controlled companies.

It seems a bit rum to change the rules for a single firm, however large.

Voluntary tax

It may have passed you by that Norway recently set up a system to allow people to pay more tax than they owe.

- Between the 5.3M inhabitants of the country, a grand total of $1325 has been raised so far.

It turns out that the US government has a similar – and similarly unsuccessful – webpage.

- Perhaps people don’t think that politicians are better at spending their money than they are themselves.

Twitter pics

We have seven pictures this week.

- The first was about the market share of passive funds in the US.

Their share is increasing, but more slowly than I thought.

- It’s up from 28% in 2014 to 37% now.

- I thought it was already much closer to 50%.

Mind you, at that rate of travel, passive funds will be in the majority within five years.

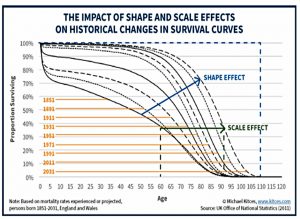

This one, from Michael Kitces but using UK data, shows that the increase in life expectancy comes more and more from the growing lump of people in the middle who live longer, rather than from the smaller group of people who are extremely long-lived.

- Note that the data here covers 180 years.

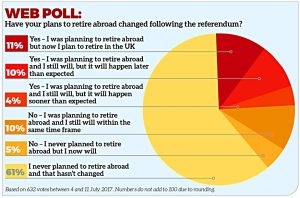

The next one looks at how the Brexit vote affected plans to retire abroad.

- 11% decided to stay in the UK, and 5% decided to retire abroad.

It was the General Election (and specifically the 40% vote for Corbyn) that got me thinking, so I’d like to see a similar poll for the June 2017 votel.

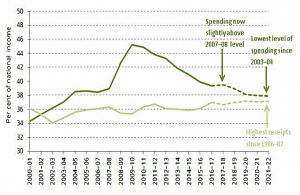

This next one shows government spending vs receipts (as a proportion of GDP).

- The spending peak in 2010 was where Gordon Brown handed over the reins, and the period since has seen lower spending and more taxes.

- But still not enough to close the gap, even if we project forwards to 2022.

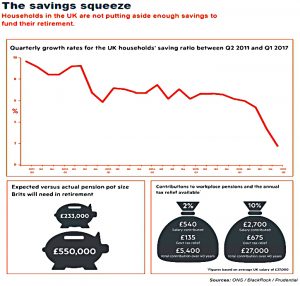

This one shows the sorry state of UK savings.

- We have the lowest savings ratio on record, and people’s targets for their pension pots are only 43% of what they will actually need.

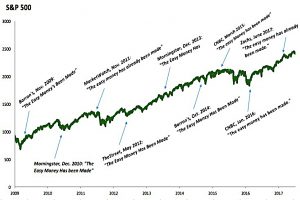

This one shows how hard it is to call the top of a market.

- Shouts of “the easy money has been made” date back to November 2009.

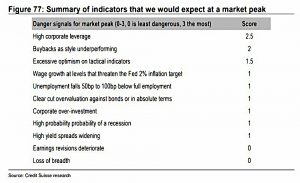

And finally we have Credit Suisse’s scorecard of peak indicators.

- They don’t seem too worried, scoring us at 12 out of 33.

Until next time.

Good articles Mike,

One of the downsides of the Carillion debacle is that it is automatically in FTSE 250 trackers and even worse still, it is in the IUKD ishare UK dividend ETF (where it was its second biggest holding) and the SPDR S&P UK Dividend Aristocrats (where it was the 4th biggest at around 5% of its holdings)- it had been suggested previously that the latter was a safer option for high yield equities because it had a screening process to determine its index whilst the former was based on yield only- clearly the screening failed to look at the shorting going on!

The other downside is that IUKD have already taken Carillion out of their fund as it no longer pays a dividend so presumbly would miss out on it recents 20+% rise?

As far as I can tell the SPDR still holds the firm-interesting!