Weekly Roundup, 6th June 2017

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup as usual in the FT, with the Chart That Tells A Story. This week it was about consumer debt.

Credit card debts

Lucy Warwick-Ching looked at credit card debts.

- Lending to UK consumers went down briefly during the 2007-08 crisis, but is now significantly higher once more.

- There are 64M cards in use and the total debt has reached £68bn.

Industry observers blame competition for borrowers in an era of low interest rates, (( Not that the rates on credit cards are low )) which has led to an increase in zero-rate balance transfers.

- These can now last for more than three years.

People are starting to get worried and the party manifestos include proposals for “statutory payment plans” for those in difficulties.

- While it’s hard not to feel sympathy for those in difficulties, I think we are looking at this problem from the wrong angle.

We need to make credit harder to come by, particularly for those who are least likely to re-pay.

- And we need to get interest rates back up to normal levels (higher than inflation would be a start).

Land Tax

In the Telegraph, Gordon Rayner wrote about Labour’s plans for a Land Tax (or Land Value Tax, LVT) which was immediately dubbed a “garden tax”.

- It’s no more a garden tax than Theresa May’s social care mistake was a dementia tax – the value of gardens is theoretically already included in council tax – but that’s the kind of politics we have today.

- It’s not really a land tax, either, as for most people it will simply be calculated from the value of their home – you don’t need a garden or even a freehold to qualify.

The headline was that the tax would be three times higher than the existing council tax, but for obvious reasons, I’m more concerned about the impact at the extremes.

In theory, a Land Tax takes no account of whether land has been developed (built on) – an empty plot has the same value (usually based around some form or market or imputed rental value) as the house next door.

- In practice, the Labour plan – driven by a group called the Labour Land Campaign – simply assumes that 55% of the value of a house comes from its land.

- This is clearly nonsense, with land values varying widely across the country.

The Land Tax would then be applied at 3% of this 55%.

- So it’s really just a 1.65% annual tax on owning a home.

The Labour Land Campaign says that the inevitable drop in house prices would be:

One of the long-term benefits of LVT.

Meanwhile the Land Value Taxation Campaign goes further:

Land value owes nothing to individual effort and everything to the community at large. It belongs justly and uniquely to the community.

So communism, basically.

- The fans of LVT see it as a rent collected by the State, which in their eyes ultimately owns the land.

- This can be collected either from the tenant (if the land is used productively) or the landlord (if the land is not used productively).

Those of us who own a house are seen as excluding the masses from a “valuable natural resource”.

- Luckily we still form the majority of the population (64% at last count).

Here in central London, my annual bill would be more than £25K each year.

- That’s ten times my current council tax bill, and the vast majority of my annual pension income.

- So I would need to sell or take out equity release to fund the payments.

And compounded over 50 years of home ownership (( I first bought aged 26 )) it means that you would hand 56.5% of the value of your home to the government.

I’m against wealth taxes of all stripes.

- To the extent that there should be any taxes at all, they should be on income and consumption (via VAT).

- Everything else depends too much on decisions made by individuals about their current and future lifestyle.

In particular, people who want to defer consumption until later in their lives should not be penalised.

- But if we must have a wealth tax – and that’s all this is, really – then it should apply equally to all assets, rather than just one type.

And there should be savings vehicles which are ring-fenced.

- I would suggest SIPPs, ISAs and your primary residence (which would rule out an LVT).

Over at the Adam Smith Institute, Sam Bowman wrote a piece with the modest title: “Why everybody is wrong about the Land Value Tax (except me)“.

- He points out that a genuine LVT would be better than council tax (and business rates) since the latter tax productive investment and development, which means that we get less of them.

- The beauty of a true LVT is that we wouldn’t end up with less land.

Sam also notes that council tax can be seen as a tax on consuming housing (a la VAT), which works for me to some extent.

Sam would also like to see harmonisation between the tax on business property and residential property.

- Business rates are five to ten times higher, which leads to more residential development than otherwise.

But he rejects that argument that LVT would lead to land being used “more productively”.

- Opportunity cost (loss of potential rent) should already do that job.

- An extra tax would be a bit like taxing leisure time – you raise more money but people aren’t actually better off.

Sam also rejects the idea that land ownership leads to unearned economic rents, since the purchase price of the asset must have discounted this future income.

And he points out that the introduction of an LVT would immediately reduce the value of land (property), meaning that the existing owners would in effect pick up all the future tax.

- It’s a one-off grab from people who own their homes, in the same way that a new school or tube station is a one-off windfall to those who happen to live nearby.

This means in turn that the LVT should be generally equivalent in size to the property taxes it replaces, which kind of defeats the point of bringing it in.

And finally, Sam agrees with me that singling out property for an asset tax is unfair.

- He likens it to a tax on people with ginger hair – hard for them to avoid, and not leading to fewer ginger people, but unjust.

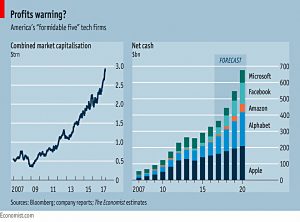

Tech stocks

Back in the FT, Merryn was warning against buying into the US tech giants, at least with a long-term (10-year) view.

- It’s a superficially attractive sector with market-dominating firms that show fantastic past and potentially future growth – as we noted here.

- But Merryn thinks that changes are afoot.

To begin with, they are now all too expensive.

- The growth to value stocks ratio just went past its year 2000 level.

- The Nasdaq Internet index now trades at 61 times earnings (though in the dot com boom the Nasdaq 100 hit 205 times).

But the real threat is regulatory.

- Following the terror attacks over the past couple of weeks, the UK government has been making noises about forcing the internet firms to work harder to control what is available online.

- Such policing would be expensive.

But even without terror, most of these firms are de facto monopolies, and natural targets for regulation and increased taxation.

- There’s already plenty of public anger about how little local taxes most of them pay.

Over in the Economist, Schumpeter looked at the cash piles hoarded by these same firms.

- If these firms are going to dominate the world, why do they hoard cash as if in preparation for a crisis?

- Old-economy oligopolists (telecoms and beer firms, for example) use a lot of debt and return most of the cash they generate to investors.

In contrast, the big five tech firms (Apple, Google, Microsoft, Amazon and Facebook) have $330 bn of net cash – two years of cashflow.

- And the pile will likely grow, as only Apple pays a meaty dividend.

- By 2020 the cash pile could be three times cash flow.

We all know that part of the story is tax.

- US firms only get taxed on their foreign cash when they repatriate it, so they don’t.

- That accounts for 80% of the cash.

It could also be that they are as worried as Merryn is about regulation impacting their profits.

- Or they could be planning giant acquisitions of potential competitors, like car firms or media companies.

Growth vs value

Back in the FT, Robin Wrigglesworth wrote in more detail about the growth-value disparity mentioned by Merryn.

- The run is testing the patience of value investors.

In time the tech stocks will crash and the value stocks will outperform.

- But that final burst of universal euphoria remains elusive.

Since the US market, and tech in particular, is most overheated, diversification is prudent.

Two FTSEs

Continuing with the “tale of two cities” theme, Michael Mackenzie looked at the foreign earners in the FTSE-100 compared with the UK earners. (( John Authers is still “away”, but I see that he’s been active on Twitter, so I’m not too worried yet ))

- As you might imagine, the Forex earners have outperformed.

Michael also notes that the 2-yr Gilt is trading at 0.1%, below the 0.25% of the BoE’s overnight rate.

- This inversion, echoed by the the 1% yield on the 10-year gilt, implies a hard brexit, with possibly “no deal better than a bad deal”.

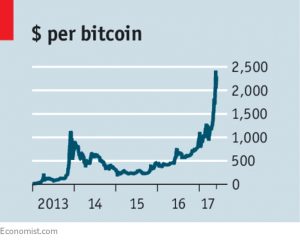

Bitcoin

The Economist looked at the Bitcoin bubble – if it is such a thing.

The price certainly has rocketed upwards:

- It’s doubled in two months.

- $1K invested in 2010 would now be worth $46M.

The Economist wanted to know whether Bitcoin is “a tulip, gold or the dollar – or something else entirely.”

- It’s better than tulips, because you can buy things with it directly.

- It shares a lack of government control (and potential central bank mis-management) with gold, but its price is far more volatile.

- It aspires to be a medium of exchange, like other currencies, but the system is running at its limits.

- Each transaction now costs $4 and takes hours to be confirmed.

The newspaper thinks that Bitcoin is more like the dot com firms:

- The combination of private money and public records allows for many experiments to be undertaken.

Since the participants are largely aware of the risks, and the system is fairly self-contained, they pronounce Bitcoin and the other cryptocurrencies that rare beast – a healthy bubble that might lead to useful innovation.

Abolish ISAs

Paul Lewis was back in the FT with another “brave” article.

- This time he wants to scrap ISAs.

As you might remember, Paul is a big fan of cash, and he looks at ISAs through that lens.

- For him, we only need Cash ISAs, and the point of an ISA is to protect your interest from tax.

I actually agree with Paul that the proliferation of types of ISA over recent years has got out of hand.

- But I also believe that stocks are a far better long-terms savings vehicle than cash.

For Paul, the collapse in interest rates since John Major introduced the TESSA (the fore-runner of the Cash ISA) (( The precursor of the stocks and shares ISA was the PEP )) way back in 1990 – they are down from 13.5% to 0.25% – means that the usefulness of the ISA has been greatly diminished.

- The basic rate of income tax has also come down from 25% to 20%, further reducing the tax savings.

And the first £1,000 of interest is now tax free in any case.

- That will take care of the first £50K to £100K of savings, depending on what kind of account you have it in.

And non-ISA accounts often pay more than ISA accounts, introducing a further trade-off.

Paul also thinks that stocks and shares ISAs are “becoming pointless for ordinary investors”.

He mentions the £5K dividend allowance, even though this will be cut to £2K after the election.

- With the FTSE yield at £3.5%, the current allowance shelters dividends from £140K, though the £2K allowance will only shelter around £55K.

And he plays down the significance of the capital gains exemption, since your gains need to exceed £11.3K pa for this to apply.

Paul has this all wrong.

- ISAs are a long-term savings vehicle, like SIPPs and other pensions.

- They aren’t for stashing away a wad of cash for a few years

To reach financial independence, most people will need to build up a pot of more than £750K, outside of their house.

- Such a pot will throw off average annual gains of more than £35K, so ISAs help a lot.

- They save on paperwork, and help you to avoid unnecessary trades, as well as save tax.

Saving to secure your future doesn’t make you wealthy.

- And using an ISA to do it isn’t taking advantage of a “tax haven”.

I’d be happy to meet Paul halfway, and abolish Cash ISAs.

- Then perhaps more people would invest in stocks for the long-term.

To use a football analogy, Paul manages to combine the attention-seeking behaviour of Mourinho with the clinging-on-past-his-sell-by-date approach of Wenger.

- We need some new financial journalists along the lines of Klopp and Conte. (( I am available, if anyone is interested ))

Until next time.