Weekly Roundup, 30th May 2017

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup in the FT, with the Chart That Tells A Story. This week it was a comparison between the performance of two REITs.

Contents

REITs

Aime Williams compared Segro and Intu Properties.

- Intu owns shopping centres across the UK, renting units to firms like Next, Zara and the now-defunct BHS.

- Segro – formerly Slough Estates – focuses on warehouses larger than 100K sq ft – nowadays often referred to as sheds or Big Boxes – in out-of-town business parks.

- Segro also owns most of the cargo facilities at Heathrow.

Segro has clearly had the better of the last two years, and it poised to replace Intu in the FTSE-100 at the end of the month.

- The rise of internet shopping means that high street stores are out of favour, but the logistics hubs used by the internet firms are in vogue.

- Post-Brexit inflation – an increase in the cost of imports from sterling’s devaluation – could make things even harder for the high street, though sales haven’t dropped off too badly so far.

Zopa and Funding Circle

Aime’s second article of the week was on Zopa, which announced more details about its forthcoming Innovative Finance ISA.

- Rival operator Funding Circle also received FCA approval for an IF-ISA last week.

In theory, P2P is an interesting asset class, and it’s the lack of a tax wrapper that has put me off the most.

- But I really don’t want to have to park £20K with each of the major providers.

So until (if ever) someone comes up with a platform that lets me spread my IF-ISA across providers, I’ll stick with the investment trusts that invest in P2P loans.

Zopa said that the ISA would target a return after fees of 3.9% pa (slightly higher than the 3.7% available on its “classic” product).

- This is because the safeguard fund designed to protect against defaults is not being offered within the IF-ISA.

- The fund will be phased out completely by December this year.

Social Care

In her FT column this week, Merryn attempted to tie together asset management fees and funding for social care.

- At least that was what the headline suggested – the article merely pointed out that if investors hung on to more of their pot, they would be less reliant on the state in general, and probably on social care in particular.

- And there is plenty of precedent for price caps in investment.

There’s little doubt that fees are too high and asset managers are too profitable, but there’s no direct link to social care.

- You might as well argue for a cap on footballers’ salaries.

People need to vote with their feet, and put their money with the cheapest providers.

The Economist also returned to the topic of social care.

- After commenting on the scale of Theresa May’s U-turn, they looked at whether a private insurance market might develop.

This would require a low-ish cap on individual contributions.

- But even then the experience of the US is that conditions like dementia are becoming more prevalent faster than the risk assessments allow for.

- And a low cap might mean that few retirees wanted to pay for insurance anyway.

Buffet ratio

In her MoneyWeek column, Merryn looked at valuation measures for US stocks, including the “Buffet Ratio“.

- This is the value of listed US stocks compared to GDP.

- You buy at 0.7 and sell at 2.0 (sa in 1999).

It’s at 1.9 just now, but Buffet says that stocks are cheap-ish for now because inflation, unemployment and bond yields all remain low.

- Other flashing lights included PE, price to sales, and the CAPE.

Multi-factor investing

Also in MoneyWeek, David Stevenson looked at multifactor investing – or as he called it, “filtering out the rubbish”.

- Most investors will be familiar by now with factor investing (quality, value, momentum) and with the smart beta funds built around these factors.

The problem is that no factor works all of the time.

- So you need to switch between them to get the greatest benefit.

But what about a multi-factor fund, that just invested in the best stocks from each factor?

- That might sound at first as though you would be back to investing in the market index.

- But in fact, you would be missing out on all the “rubbish” that leads to underperformance.

This sounds fine in theory, but in practice the funds that do this (from iShares and Goldman Sachs) have underperformed to date.

- David think this is because we’ve been in a bull market for eight years.

- The absence of rubbish should be an advantage when a downturn comes.

Watch this space.

Smart beta also came up in the Economist, which looked at how theory (mostly the efficient markets theory – EMT) interacts with the real-world behaviour of traders.

The rise of the EMT in the 1960s and 1970s lead to the conclusion that markets couldn’t be beaten, and hence to the formation of passive index funds, which are now wildly popular with younger investors.

- They have only reached a 20% global share of assets, but that number increases every year.

The problem with EMT is that it doesn’t explain crashes, or volatility in general.

- Why should investors keep changing their mind about what stocks are worth?

- The fundamental data (the cash flows received from stocks) are much more stable.

It also doesn’t explain why certain traders and trades (eg. the FX carry trade, value, small size, momentum, low volatility) are reliably successful.

- At the same time, the rise of smart beta funds to exploit the best factors for outperformance is likely to mean that those factors outperform by less in the future.

A third problem is that it does not deal with human psychology, assuming that all market participants are rational.

And even more fundamentally, why trade at all if you won’t be profitable (because everyone has the same information)?

- But if no one has an incentive to trade, how is relevant information to be reflected in prices?

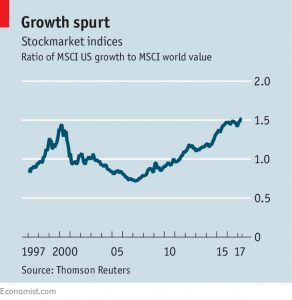

In something of a leap, the article closes by noting that growth stocks (mostly tech firms) are now as expensive relative to value stocks as they were in the dot com bubble.

- Is this because of the shift to quant approaches?

- Are all the computers crunching the same data, and buying the same stocks?

And if they are, what happens in a panic?

Central bank balance sheets

Michael Mackenzie has been standing in for John Authers at the FT’s Long View column.

- This week he looked at central bank balance sheets.

In July it will be ten years since the fallout from the subprime mortgage crisis began.

- Since then markets have been dominated by the actions of central banks, whose balance sheets have soared as a result of QE.

- In 2017 alone, $1.1 trn has been pumped into the system, taking the total for the four main banks past $13 trn.

But now the Fed is about to scale back, and the ECB is expected to follow.

- By not fully reinvesting the run-off of maturing debt, the Fed will take no more than $10 bn to $15 bn per month from its $4.2 trn total.

Michael worries that the slow tightening will risk an 1999-style euphoric blow-off.

- There was even a brief rally after the first problems in 2007.

He also worries that low volatility, excessive trend-following and groupthink mean that we could be approaching a “Minsky moment” – the point at which stability turns to instability, the tipping point.

It’s easy to see what he means, yet the market rises of the past couple of years have been anything but euphoric, with Cassandras out in force at every stage.

Tech unicorns

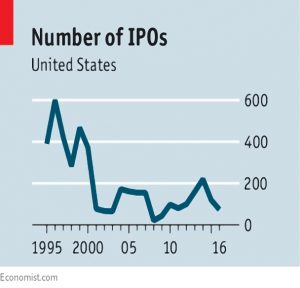

The Economist was worried that tech startups are staying privately held for longer – a topic that we’ve discussed before.

- Twenty years ago the US had 8,000 listed firms – now it’s closer to 4,000.

And the number of IPOs is falling.

- There were 74 in 2016, compared to 600 twenty years earlier.

There’s too much regulation putting off new firms, and mergers are reducing both numbers and competition.

- This means that investors can’t share in much of the wealth being created.

But there’s little downside for the startups, with plenty of private capital from institutional investors and sovereign wealth funds.

- This week SoftBank raised $93 bn for a tech fund, $45 bn of it from Saudi Arabia.

Of course the Economist would rather that they listed, citing the problems with unlisted firms like Theranos and Uber.

- They see private markets opening up to funds which would allow access to a wider group of investors, and public markets behaving more like private ones (eg. the two-tier share structure used by Snap).

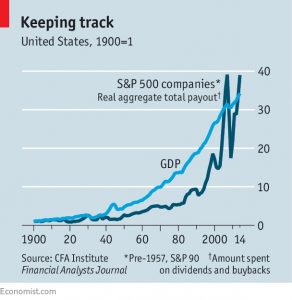

Buttonwood looked at the effect of share-buybacks on stock returns.

Most of the very long-term return on shares comes from the compounding up of reinvested dividends.

- This is because valuation levels (PE ratios) fluctuate around a mean, and growing earnings are needed for a share to rise in value.

But over the past 30 years, US firms have been more likely to buy-back shares instead.

- These can have tax advantages for investors.

- By reducing the number of shares in issue, they can also drive up the share price, which is helpful for executives with stock options.

Share numbers will be increased when shares are issued to fund acquisitions (and options).

- Overall the trend is for shares in issue to increase, though they have shrunk over the 10 years to 2014.

A new paper finds that adding buy-back returns to dividends to produce a “total payout ratio” is a better predictor of future returns than dividends alone.

- It also helps to tie the performance of the stock market to GDP growth.

Going back to 1871, the average dividend yield is 4.5%, and the total payout 4.89%.

- Since 1970, the dividend yield has fallen to 3.03%, but the total payout only to 4.26%.

But the recent growth rate in the payout yield has been 3.44% pa, compared with the long-run average of 2.05% pa.

- This is because corporate profits have risen to a post-1945 high as a proportion of GDP.

The authors of the paper have looked at using the cyclically adjusted total yield (CATY) as an alternative to CAPE, and found that it was just as good (or as bad, if you prefer) at predicting market movements.

- They are currently forecasting future real returns of 5.1% pa, compared to just 3.6% pa real if only dividends are used.

Buttonwood notes that even these returns won’t fix the holes in US pension schemes.

- But they would do quite nicely for me.

Population growth and returns

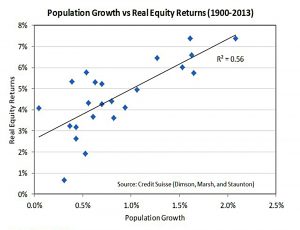

And finally, a chart I found on Twitter which looks like it was taken from one of the Credit Suisse annual reviews of returns on equities, bond and cash.

It shows how population growth is correlated with equity returns.

- Potentially bad news if this general election really does lead to a crackdown on immigration.

Until next time.