Irregular Roundup, 21st December 2023

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup with the bond market.

The bond market

The Economist was worried about the Treasury market.

American government bonds are the bedrock of global finance: their yields are the “risk-free” rates upon which all asset pricing is based. Yet such yields have become extremely volatile, and measures of market liquidity look thin.

US government debt is now 96% of GDP and servicing the debt costs 20% of government spending.

- The Fed is selling Treasuries as part of QT, but more bonds are being issued, and regulators are worried about hedge fund activity in a thin market.

New facilities for repo markets, through which the Fed can transact directly with the private sector, were put in place in 2021. Weekly reports for market participants on secondary trading have been replaced with more detailed daily updates.

More reforms have been proposed by the SEC, and they are not popular.

- The biggest change is central clearing rather than “bilateral” (OTC) trading.

This would make market positions more transparent, eliminate bilateral counterparty risk and usher in an “all to all” market structure, easing pressure on dealers to intermediate trades.

The most controversial proposal is that hedge funds active in the “basis trade” (arbitrage) between futures and the underlying market should be designated as dealer-brokers (making them subject to more regulation).

Hedge funds will go short, selling a contract to deliver a Treasury, in the futures market and then buy that Treasury in the cash market. They often then repo the Treasury for cash, which they use as capital to put on more and more basis trades.

In some cases funds apparently rinse and repeat this to the extent that they end up levered 50 to one against their initial capital.

The SEC is considering limiting hedge fund leverage.

Ken Griffin of Citadel pointed out that the basis trade reduces financing costs for the Treasury by enabling demand in the futures market to drive down yields in the cash market.

The Treasury also has proposals:

Buybacks would involve the Treasury buying up older, less liquid issuance—say, ten-year bonds issued six months ago—in exchange for new and more liquid ten-years, which it is expected to start doing from 2024.

Some of these changes seem positive, but the key measure is liquidity – a flawed market is infinitely better than no trading.

Shifting blame

Joachim Klement looked at the five strategies used by experts when their forecasts fail (as described by Philip Tetlock of Superforecasting fame):

- “if only” some pre-condition had been met (“real socialism has never been tried”)

- Ceteris paribus (but things are never equal, or the same)

- Almost (apart from an unforeseeable shock)

- Eventually (it will come true if you wait long enough)

- The framework is correct, and individual forecasts are less important.

Joachim’s colleagues at Liuberum have extended this work by looking at what equity analysts do when they get things wrong.

Shame is a major blocker to change, and the level of shame depends on several factors:

- is the analyst an expert on this stock, or is this a minor forecast?

- was there an external change that explained the failure (eg. regulation)?

- was the prediction particularly bold?

- how quickly did things go wrong?

- did the forecast gain a lot of traction with investors before it went wrong?

Joachim explains the best course of action:

Being honest and transparent about your mistake, going out in public with your hat in hand and telling everyone you were wrong and why you were wrong (no excuses, please) is the best policy. This will enhance your reputation, not reduce it.

There is a trust equation to back this up:

Trust = (Credibility + Reliability + Intimacy) / Self-orientation

The last two terms explain why I have problems getting strangers to trust me.

Sadly, the analysts used three alternative strategies:

- head in the sand (denial, refusal to update the forecast)

- paralysis (switch to a “hold” recommendation and sit on the sidelines)

- “babies and bathtubs” (wholesale change)

Joachim says that these coping mechanisms are doomed.

By admitting to mistakes and honestly assessing them in a post-mortem – even if that means public humiliation – my forecasts got better over time. Be a man about them, not a coward.

We all make mistakes – the key thing is to learn from them.

A second article looked at how fund managers cope.

A study by Meng Wang from Georgia State University used a GPT-based large language model and trained it on the discussion of their funds’ performance fund managers provide.

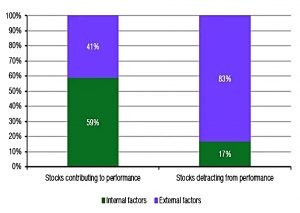

The simple split between internal reasons (investment process, fund manager skill, etc.) and external reasons (market circumstances, macroeconomic developments, etc.) shows that fund managers are just as good at shifting blame as research analysts.

It gets worse:

The fund managers who are more prone to this self-attribution bias tend to trade more and see their performance drop in the subsequent quarter. Overconfident fund managers think that their success is all based on their skills and not due to luck.

Are private investors any different?

Lifestyling

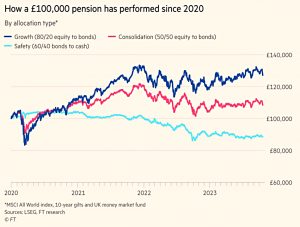

In the FT, the Lex column looked at the dangers of lifestyling to those with DC pension schemes, given the recent crash in bond prices in the light of interest rate hikes.

Lifestyle funds give younger savers heavy exposure to equities with the aspiration of long-term growth. Older customers are funnelled into bonds with the aim of locking in gains. Savings companies may, in some cases, have transferred their nest eggs into bonds at the worst possible time.

This made sense before the pension reforms of 2015 when investors had to buy an annuity (eventually).

- Moving into bonds as you approached that purchase reduced the risk of being upended by a market crash just before you retired.

But now we have flexible drawdown, which suits a constant exposure to risk assets (stocks).

The little-acknowledged danger for savers is that savings companies may shunt their money into low-return lifestyle funds too early. There will be pressure on them from compliance departments to reduce regulatory risk with a “safety first” approach. But the safety provided by bonds when interest rates are volatile has lately proved illusory.

UK taxes

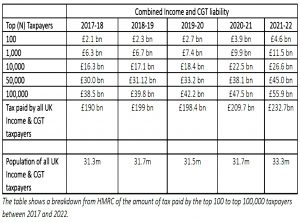

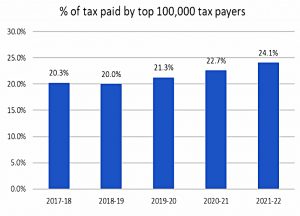

Wealth Club pointed out that contrary to popular opinion, rich people in the UK pay a lot of tax.

Britain’s top 100,000 taxpayers footed an average income and capital gains tax bill of £559,000 each in 2021/22 up by 18% from the £475,000 in the previous year. They also paid almost a quarter (24.1%) of HMRC’s annual tab from this tax, despite accounting for just 0.3% of UK taxpayers.

In total, HMRC raised £232 bn from (just) 33.3 M people.

- The top 100K paid £55 bn between them.

- The top 100 contributed £4.6 bn of that – an average of £46M each.

Founder Alex Davies said:

The overall income and capital gains tax take [the top 100K] are paying has risen by 45% in just five years, meaning not only are they paying more, but they are shouldering more of the increasingly heavy burden. The message is clear for politicians of all persuasions when deciding future tax policy – tread very carefully.

The wealthy are a mobile bunch, proven by the fact that an estimated 3,200 millionaires are expected to leave the UK this year. If the top 1,000 taxpayers migrated out of the UK, [the shortfall would be] £11.5 billion, leaving a massive gap in the country’s finances.

Bat and ball

In the FT, Tim Harford looked at the bat and ball problem.

The bat and ball problem was developed by the behavioural economist Shane Frederick of Yale University and made famous by Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman in his book Thinking, Fast and Slow. If a bat and a ball together cost $1.10, and the bat costs a dollar more than the ball, how much does the ball cost?

If you use your fast-thinking system, you come up with the tempting but wrong answer of 10 cents.

- A slower consideration leads to the correct answer of 5 cents.

People who score well on problems such as the bat and ball do a better job of distinguishing truth from partisan fake news.

A new study from Frederick and Andrew Mayer suggests that things are more complicated.

- They offered variants of the question, including hints that 10c is wrong and 5c may be right.

Others were told:

“The answer is five cents. Please enter the number five in the blank below: ___ cents.” More than 20 per cent of people did not give the correct answer despite being told exactly what they should write.

Frederick believes they are sticking with their first guess because they are afraid that the experimenter is tricking them.

Meyer and Frederick propose that we sort the responses into three buckets: the reflective (taking the time to get it right the first time), the careless (who succeed only when given a prompt to think harder) and the hopeless (who cannot solve the problem even with heavy hints).

I think the labels are fine, but the real problem is how difficult it is to move people from their default group into a better one.

Munger ratio

We covered Charlie Munger’s death last week, but amongst all the tributes, I came across the Munger Ratio.

- Although I’d never heard of it before, it turns out that I’ve been using it for many years.

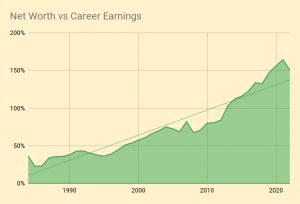

The Munger Ratio is the ratio of your net worth to your cumulative lifetime earned income (or career earnings, as I call them).

- Charlie used this to determine when to quit work and take up investing (or in his case, wealth management) full-time.

Charlie was a lawyer before he was Warren’s partner, and he had several children to provide for.

- After 13 years of work, he found that his portfolio was larger than his earnings from the law, so he decided to quit.

This Munger Ratio of 1 has been referred to as the Munger Threshold.

It took me around 28 years, but I finally crossed the threshold myself and quit work around eleven and a half years ago.

- I calculate the Munger Ratio at the end of each year when I carry out the annual review of my portfolio.

Last year it was around 1.5.

Quick Links

I have nine for you this week, the first four from The Economist:

- The Economist explained Why stockpickers should get out more

- And examined The mystery of Britain’s dirt-cheap stockmarket

- And told us What Google’s antitrust defeat means for the app economy

- And bade us Welcome to the ad-free internet.

- Bloomberg said that The Stock-Bond Party Is Running Out of Punch

- Discipline Funds asked Did Interest Rates Just Peak?

- Alpha Architect looked at The Temptation of Factor Timing

- UK Dividend Stocks asked Should dividend investors buy Lloyds Banking Group?

- And Of Dollars and Data asked What is the Safe Withdrawal Rate in Retirement?

Until next time.