Weekly Roundup, 6th September 2016

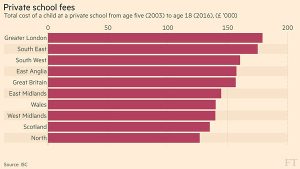

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup in the FT, with the Chart That Tells A Story. This week it was about public school fees.

Public school fees

Hugh Greenhalgh looked at some research from Lloyds Private Banking which showed that 13 years of private schooling in London (begun at age 5 in 2003) would cost £180K in total.

- The average for the UK was £160K.

- The average annual bill is now £13.3K, up from £7.3K in 2003.

- School fees are up 21% over five years, compared with a 13% increase in RPI and a 5% increase in wages.

Costs have apparently been pushed by an increase in demand from foreign students.

- And they haven’t stopped rising yet – Lloyds estimates that a child who started school last year will cost £286K in total over 13 years.

The astonishing thing is that these are just the fees for days schools.

- A child switching to boarding at age 13 could rack up a total bill of £468K.

That is a serious amount of money, and it’s hard to believe that even the advantages of public school could repay that kind of investment.

- But the parents of 625 thousand children clearly think that it does.

Tax bills and Post-its

Hugo’s second article was about the news that HMRC plans to add hand-written post-it notes to their letters, urging taxpayers to get in touch.

- This is a “Nudge” initiative – the kind of thing that Cameron’s Behavioural Insight team came up with in their 2012 report.

- The idea is that taxpayers will feel they are under special scrutiny and take the letters more seriously.

- I’m sure it will work, though it does feel a bit Big Brother.

Coincidentally, I’m on holiday in Cornwall this week and re-reading the Freakonomics books.

- The third in the series – Think Like A Freak – tells the story of how the authors were called in to Cameron to advise him.

[amazon template=thumbnail&asin=B018EX4M3A]

Spotting that the NHS cost 10% of GDP and was free at the point of consumption, they advised Cameron to bring in charges for doctors’ appointments and A&E visits.

- They never heard from him again.

Politics will always trump economics here in the UK.

Trivia

Sticking with psychology, Tim Harford looked this week at trivia.

He began with the Dunning-Kruger effect, which states that while talented and clever individuals are aware that they are above average, the stupid and useless have no idea of their situation.

- This very much matches my own experience of life.

[amazon template=thumbnail&asin=1786070138]

In a new book called Head in the Cloud, William Poundstone argues that trivia could be a defence against Dunning-Kruger.

- If we know a little bit about a lot of things, we are more likely to realise when we don’t know enough.

- People with a good grasp of trivia are paying attention.

A recent experiment asked young people (average age 20) a series of trivia questions.

Here are seven examples:

- What is the name of the large hairy spider that lives near bananas?

- What is the spear-like object thrown around in athletics contests?

- Which country’s capital is Baghdad?

- Who is Flash Gordon’s girlfriend?

- Who wrote The Brothers Karamazov?

- Who was the first man to run a four-minute mile?

- Which mountain range separates Europe and Asia?

How did you do? ((I scored 100% ))

The success rate on the first 3 questions was below 50%, but on the last four questions, none of the hundreds of participants scored a single point.

- There were 50 such questions, to which no undergraduate gave the right answer.

There’s a lot that kids today don’t know, and they don’t know that they don’t know.

- As Poundstone puts its, the one thing that you can’t google is what you should be googling.

EIS and VCT

Emily Perryman looked at EIS and VCTs as ways around the continuing squeeze on pension tax relief.

- I’m not sure how many readers are caught by the annual or lifetime allowances, but it’s a good opportunity to look at the alternative tax breaks.

First the definitions.

A VCT trades on the stock market and is like an investment trust that can only invest in small (usually unlisted, but sometimes AIM-listed) businesses.

- Many VCTs invest in 40 or more firms.

- You get 30% tax relief up front but must hold the shares for 5 years.

- Capital gains and dividends are tax-free, but there is no IHT relief.

- You can invest up to £200K per year, and the minimum investment per fund is usually £5K.

- 70% of the money must be invested within 3 years.

- Qualifying firms have assets of less than £15M and fewer than 250 employees.

- Management buy-outs and renewable energy are not allowed, nor are companies that are more than 7 years old.

VCTs have a reputation for being illiquid, but I have held dozens of them and never had a problem in selling into the secondary market.

- That said, I have never tried to dispose of a holding in a single fund that was larger than £7K or £8K.

- In addition, there are some “planned exit” funds, and some firms buy back shares at a small discount to net asset value.

EISs are typically smaller and less diversified than VCTs.

- They might invest in a handful of businesses, or even just one.

- You get 30% tax relief but must hold the shares for 3 years.

- Capital gains are tax-free and existing capital gains can be deferred by investing in EIS.

- You can invest up to £1M per year and the minimum per scheme is usually £25K.

- Dividends are not tax-free (and so are not usually paid out).

- Getting out requires all the underlying holdings to be sold and the holding period is usually 7 to 10 years.

- EISs invest in the same companies at VCTs, but need to spend their money within two years.

- Each underlying company can only receive £12M of investment (apart from “knowledge-intensive” companies, which can receive £20M).

There is also IHT relief after two years.

- This is attractive, but the same tax break is available on most AIM-listed shares, and we’ve looked previously at putting together a diversified portfolio of 50 AIM shares.

- This would be much harder to do with EIS, so unless you need the income tax relief up front, stick with AIM for this.

I confess to not seeing the attractions of EIS – they are just less diversified versions of VCTs, with higher minimum investment levels.

- Their only advantage is IHT relief, and that is better accessed through AIM stocks.

VCTs can be attractive to those who have used up their pension allowance, and also to those needing income, since many yield more than 5% tax-free. ((Disclosure – I don’t currently hold any VCTs or EISs ))

- They are less attractive than a decade ago, since the holding period has increased and the pool of eligible companies has shrunk. ((This was largely due to EU restrictions on state aid and could possibly be reversed on Brexit ))

Emily’s article focused on this year’s market for VCTs and EISs, and is well worth reading if you are already looking.

- There are likely to be fewer launches and higher demand than usual, so Emily advises that you get in early.

- Competition between funds is also likely to drive up valuations of underlying investments, as companies hold “beauty parades” for investment managers.

10 years of hindsight

John Authers has been writing his Long View column in the FT for a decade now.

- He decided to look back at what would have been the right bets for his imaginary firm Hindsight Capital to have made ten years ago.

The US stock market is up 69.4%, while the rest of the world is up only 8% and Europe is down 12.6%.

- Developed markets are up 28%, while emerging markets are up 14%.

- Long bonds returned 8.4% pa, compared to 7.7% for the S&P 500.

Despite the unusual experience of low-risk investments beating riskier ones, John takes the lesson to be that diversification works.

He has a few more investing rules:

- always worry about costs – these are known and controllable, unlike returns

- be humble – the market is efficient enough to be close to impossible to beat, so use passive funds

- rebalancing is a gift that keeps on giving

- it’s as risky to be out of the market as in it

I don’t agree that you can’t beat the market, but it’s not a strategy for most people.

- Other than that, it’s not a bad set of rules.

John also graciously quotes Jason Zwieg, who writes a similar column in the Wall Street Journal:

My job is to write the exact same thing between 50 and 100 times a year in such a way that neither my editors nor my readers will ever think that I am repeating myself.

I don’t have an editor, but I know how they feel.

I’m on holiday this week, so this column is unusual in that it is a work in progress.

- I’m very likely to add to it over the next couple of days, so please do check back later in the week.

Until next time.