Weekly Roundup, 13th September 2016

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup in the FT, with the Chart That Tells A Story. This week it was about the Brexit rebound.

Contents

Brexit rebound

Emily Cadman looked at the UK Services PMI survey – a measure of confidence amongst purchasing managers.

The chart below plots the survey results against UK GDP growth.

- As you can see, the PMI survey has a good record in detecting turning points in the economy.

- Just after Brexit, the survey was predicting a UK recession, but confidence has now returned.

Of course, Brexit hasn’t happened yet. ((Indeed, some of us suspect that for Mrs. May, Brexit doesn’t mean what you voted for when you voted for Brexit ))

- The impacts of the change will only be known years after the vote.

- And Emily notes that the survey is constructed so as to be sensitive to small changes in mood.

Nor is the current recovery strong enough to head off a further UK interest rate cut before Xmas, though November now looks more likely than September.

- Service sector output data is due in October, which could swing things one way or the other.

Bond proxies

Also in the FT, Terry Smith offered a defence of the “bond proxy” stocks that investors have recently chased up in price.

- His own fund’s strategy – to “buy good companies at good prices, then do nothing” – is a solid one.

As Terry pointed out in a previous article, the return on capital of a business is the biggest driver of an investor’s long-term returns.

- Over the short to medium-term, value and momentum strategies may do better, but they need more work.

For many long-term investors there is thus no need to change tack in advance of a period of potential underperformance for the bond proxies.

- More active investors will be looking to reposition their portfolios (see also John Authers, below).

There will be more from Terry on bond proxies – and in particular, on the lessons to be learned from the Nifty Fifty stocks of 1960s America – next week.

- And there’s more this week from John Authers, below.

Central Bank impotence

Ken Fisher reminded us that central banks can influence little beyond volatility and long-term inflation.

- He quotes Milton Friedman’s idea that central banks could be replaced with a formula for increasing the money supply – desired inflation plus expected growth.

Ken sees the key issue as whether banks will lend to “appropriate borrowers” – this determines whether the world will avoid a recession.

- The primary influence on this is the yield spread (the excess interest rate at long periods over short periods).

Here in the UK the yield spread is only 32 basis points (0.32%).

- But the global GDP-weighted spread is 0.81%, which is just enough.

The variation in spread between countries means that global banks have opportunities to make their own yield curve steeper.

- They could borrow in Denmark at -0.65% and lend in Portugal at 3%, for example.

So Britain should avoid recession, because the world will – as ever, “the strong pull the weak along”.

- And as usual, Ken says to stick with stocks.

Dying broke

Merryn wrote that the priority of wealth managers should be to make sure that their clients die close to broke.

- Wealth managers don’t see things this way, obviously.

The conventional wisdom is that capital is not for spending, even in retirement.

Which means that you still have your capital left when you die.

Merryn is advocating a “total return” approach, where it doesn’t matter how your retirement income is generated.

- This is a fine approach in principle, but because investment returns and life expectancy are both unknowns, it’s difficult to put into practice.

The solution used to be annuities, but low interest rates and high ligfe expectancy means that they now offer terrible value. ((As Merryn points out, selling your annuity in the proposed secondary market – recently rejected by Hargeaves Lansdown – falls into the “two wrongs don’t make a right” category ))

- Defined benefit pensions are very similar (but usually much more generous).

Merryn’s right that the industry doesn’t do enough in the area of decumulation, but there’s no easy answer to getting people to make the most of what they’ve saved.

- I’d like to see the government offer retirement “bonds” based on very long-term average returns – say 3.5% pa, or 1% plus inflation.

- They can afford to take the hit if the markets underperform for 20 years, whereas individuals can’t.

Lifetime ISA

Josephine Cumbo reported that the government is pressing ahead with George Osborne’s Lifetime ISA (LISA).

- The scheme lets 18-40-year-olds contribute up to £4K pa with a 25% top up added by the government.

- You can take the money out tax-free at age 60 or to buy a house worth less than £450K.

It’s not clear how many providers will offer a LISA, though Hargeaves Lansdown have said that they are on track for the April 2017 launch.

Many people worry that the LISA will attract money that should go into workplace pensions, but it looks like a niche product to me.

- If you are a high rate taxpayer, you get more tax relief in a pension.

- Any workplace pension must also have “free” employer contributions.

- The age limit for withdrawal is 60, higher than the current pensions limit (55).

- The annual contribution limit in a LISA (£4K) is much lower than in a pension (£40K).

It looks more like a product designed to prop up the property market to me.

- Only those saving for a house (outside London, where the £450K limit is too low) should be interested.

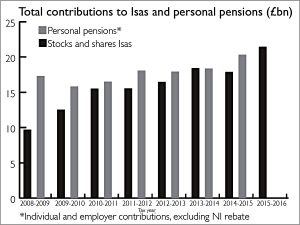

Nevertheless, there is evidence that ISAs in general are taking over from pensions.

- £21bn went into stocks ISAs in 2015-16, the highest total ever ((It should be noted that this was only 25% of total ISA contributions – the rest went into cash ))

- Only £20 bn went into pensions during 2014-15 (the latest year for which data is available)

Land Registry privatisation

The government also announced that the Land Registry will not be privatised after all, or at least not according to the original timetable.

This is welcome news.

- Although I am a big fan of free markets, recording the ownership of property strikes me as the kind of natural monopoly that is best administered by the government.

Bond yield bottom?

John Authers looked at whether bond yields have finally bottomed, after a sharp uptick last week.

- The economic data show little sign of inflationary pressure, but it’s possible that the Fed will raise rates again soon.

- John also thinks that the lack of post-Brexit turbulence (FX rates aside) has “removed a critical reason for caution by central banks”.

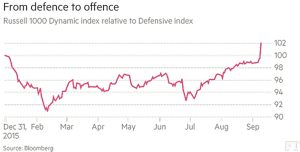

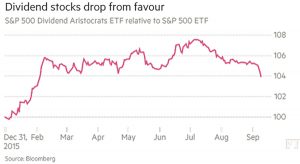

But the key factor is that markets are already behaving as though the low-yield environment is going away.

- Cyclicals – which do best when the economy is expanding – are now rallying versus defensives.

- Banks are doing the same, implying higher yields ahead.

- And high dividend payers are losing ground.

Emerging markets stocks have rallied, but their currencies have fallen.

- This again fits with a rate raise from the Fed.

John sees good times ahead for pensions deficits and banks, but pain for bonds and bond proxies.

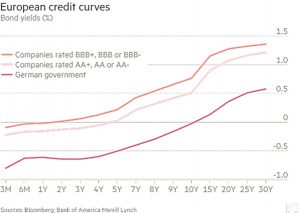

Negative corporate rates

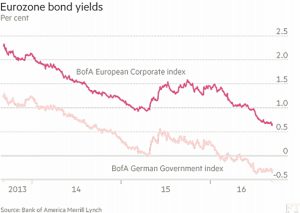

In contrast to John’s analysis, John Kay noted that a couple of European companies (one French and one German) managed to sell €1.5bn of corporate debt at negative interest rates (-0.05%).

- This is believed to be a first – only governments have managed this trick so far.

Neither company needs the money – they already have cash piles – but selling super-cheap debt allows them to profit from their treasury operations.

- As John says “people will lend you money as long as you can prove that you don’t need it”.

For private investors, this is nonsense.

- We can just keep cash under the mattress, and indeed the amount of currency in circulation is now up to €3K per head in the Eurozone.

But companies can’t park €1bn under the mattress.

- John reports that Munich Re has looked into storing its cash in heavily guarded warehouses, but there aren’t enough notes for everyone to do this.

Interest rate caps

The Economist reported that the Kenyan government has tired of its banks not lending cheaply to business, and has capped interest rates at 4% above base rate (which is admittedly 10.5%).

- Kenyan bank shares fell by 10% on the news.

Interest-rate caps are surprisingly common, existing in 76 countries in 2014.

- Most sub-Saharan countries have them and rich countries (including Britain) often have caps for things like pay-day loans.

But as usual with structural intervention, interest-rate caps produce the opposite effect from that intended.

- High interest rates are used with the riskiest borrowers.

- All a cap does is cut these people and firms off from credit.

- Many poor individuals then turn to loan-sharks instead.

Alternative strategies are also used, such as car dealers increasing the cost of cars on which loans are based.

- The customer pays the same, though the headline rate seems lower.

Its better to fix credit markets through competition and more widely available information about borrowers and lenders than through price caps.

Autumn statement

The Autumn Statement has been announced for 23rd November, and the Economist looked at what might make a good post-Brexit Budget.

- They would like a fiscal stimulus to compensate for the loss of demand that the Brexit vote could produce (because of lower business investment).

So instead of the fiscal tightening planned for 2017-18 (budget deficit reduction of 0.8% of GDP), they’d like to see more spending on infrastructure, and the cancellation of cuts to in-work benefits (tax credits etc).

Given the low-rates at which the government can borrow, I’m all for infrastructure spending.

- High-speed broadband would be useful, as would a road tunnel through the Pennines, and another runway at Gatwick.

But tax credits distort wages and the labour market, and they need to go.

- Given the imploding state of the Labour party, I expect that politics will trump fairness, and as a sop to left-wingers, they will stay.

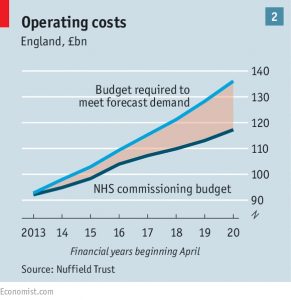

NHS

I mentioned last week the advice from the Freakonomics authors to David Cameron – that he should charge for NHS doctors’ appointments and A&E visits (as we already do for dentists and prescriptions).

- This week the Economist agrees with me.

Fifty per cent of health and social care funding goes on four percent of people.

- 70% is spent on long-term illness

- 25% of hospital spending occurs in the last 3 months of a patient’s life

They also recommend:

- a shift towards prevention rather than treatment of chronic illnesses,

- bigger, more remote hospitals (potentially by good trusts taking over bad ones)

- more social care (eg. old people’s homes)

- incentives for NHS providers also need to be shifted from “pay for procedures” to “pay for better public health”.

It’s all good stuff, apart from the underlying risk that higher taxes will be needed anyway to pay for it.

- Polls show that only a minority wants to pay more to fund a better NHS.

Grammar schools

This is not really economics, but I couldn’t ignore Theresa May’s announcement that we’ll be getting more grammar schools.

- This is a popular proposal with the public, but not so much with politicians and the media.

I qualified for the local grammar when I was a kid, but my family wouldn’t let me go as they didn’t want me to end up middle class. ((They failed in that, in the end ))

- The local comprehensive was mostly interested in maximising the number of pupils who got 5 O-levels, and the few bright kids there definitely suffered.

- When I got to Cambridge I was years behind.

So I’m definitely in favour of grammar schools.

It seems obvious to me that if we want to improve state education, we need to introduce selection.

- Selection is everywhere in life, so why shouldn’t it be in schools as well?

- I can’t see the moral objection, so long as it’s based on the ability to add-up rather than the parent’s ability to pay.

- To really fix things, we’d need to do something about public schools, but I can’t see that happening.

And it’s not just education.

- Britain seems obsessed with making everybody equal.

- And not just with equality of opportunity, but equality of outcomes, too.

But people aren’t equal, and making things appear that way inevitably means dumbing down to the lowest common denominator.

- Which in turn leaves the country vulnerable to those nations less concerned with “equality”.

Resources aren’t allocated evenly, and they never will be.

- The interesting bit is working out which set of rules gets closest to the outcomes that we’d like to see.

- Selection – in all its forms – needs to be part of that discussion.

Until next time.