Company Pension Deficits

Today’s post is about UK company pension deficits, so strap in tight.

Contents

- The Pensions Regulator

- The Pension Protection fund

- Deficits increase

- Lane Clark Peacock

- Deficits remain significant

- Contributions fell

- Contributions are lower than dividends

- Discount rates

- Inflation

- De-risking continued

- Alternatives to cash funding

- Impact of pension freedoms

- Cash balance schemes

- Continued move away from DB schemes

- The flight from equities resumed

- New inflation measure

- End of contracting out in 2016

- Conclusions

The Pensions Regulator

Last week saw the publication of the annual funding statement from The Pensions Regulator (TPR) – a non-departmental public body ((I think this is the same as a quango)) which acts as the UK regulator of work-based pension schemes.

TPR has four objectives:

- to protect pension scheme members’ benefits

- to reduce risks to the Pension Protection Fund (PPF) which partially underwrites corporate pensions; this is funded by a levy on PPF-eligible pension schemes

- to promote and improve understanding of good pensions administration

- to minimise any adverse impact on the sustainable growth of an employer from its payments into a DB pension scheme

The last of these is fairly new, dating back to a a revised funding policy for DB pensions issued in June 2014.

The Pension Protection fund

The PPF pays two levels of compensation:

- members already past retirement age (or who retired early due to ill health) receive 100% of their pension

- other members receive 90% of their pension, capped according to age (the cap at age 65 is currently £32.8K pa)

- there is also a dependent’s pension of half the member’s entitlement

Indexation is the lower of 5% and CPI, which is less generous than some schemes. If the PPF has insufficient funds to pay benefits then the level of benefits or increases can be restricted.

Deficits increase

We reported earlier this week that funding shortfalls in defined benefit pension schemes have increased, despite £44bn of extra contributions and good returns from all major asset classes. Falling interest rates are the principal cause.

The aggregate deficit of the 6,000 private sector schemes covered by the PPF was £375bn in January, up from £242bn three years earlier. It’s likely that bond market movements since January have significantly reduced the deficit.

TPR offered employers and trustees three options:

- increase deficit repair contributions, after assessing the impact on the sustainable growth of the company

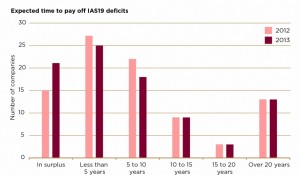

- take longer to eliminate the deficits, assuming that the company has good long-term prospects

- change their assumptions about future investment returns – ie. increase investment risk

Lane Clark Peacock

To get a better understanding of corporate pension deficits, we turned to Lane Clark & Peacock’s (LCP) annual survey of pension scheme disclosures by FTSE-100 companies – Accounting for Pensions.

LCP is a firm of financial, actuarial and business consultants, specialising in pensions and investment. The latest edition of the survey was published in mid-2014. The report identified thirteen areas of interest.

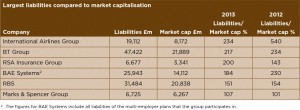

Deficits remain significant

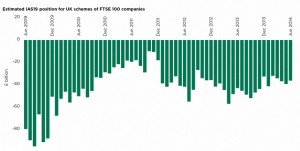

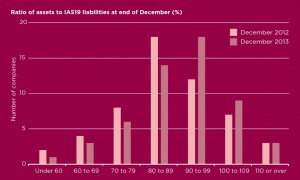

In June 2014 the deficit for FTSE 100 companies was £37 bn, compared to £43 bn in 2013

- pension assets of £475 bn represented 93% of liabilities (£512 billion) ((The highest level of cover was 133% for Royal Mail, privatised in December 2013; the company previously had a significant deficit, but the EC approved state aid to transfer most liabilities and all of its deficit to a new government scheme; when accruals were switched to track RPI rather than salaries, the surplus increased by £1.35 bn to a funding level of 183%))

- the average FTSE 100 pension liability was 37% of market capitalisation, compared to 45% in 2013

- the decrease was largely due to increases in stock prices which increased the market cap of many companies

- pension schemes still pose a significant risk for some companies – International Airlines Group’s liabilities were more than double its market cap, but because the company’s share price doubled in 2013 this was a big improvement from the previous year when liabilities were over five times its market cap

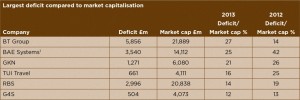

- average pension deficits were 4% of market capitalisation, down from 5% in 2012 and 2011

- for some companies, even the pension deficit is significant – BT’s deficit was more than 25% of its market cap

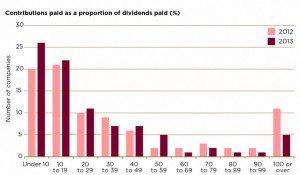

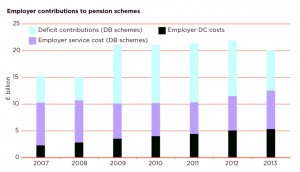

Contributions fell

Contributions fell from £21.9 bn in 2012 to £20.2 bn in 2013, despite auto-enrolment into DC schemes. There were three reasons for this:

- a significant reduction in DB deficit contributions for a small number of companies, such as BT Group, BAE Systems and Barclays that made large contributions in previous years

- the lower value of benefits in DC schemes than in DB schemes

- increasing use of non-cash funding methods

Contributions to DB schemes totalled £14.8 bn, of which £7.6 billion went towards removing deficits

- DB contributions have reduced from £16.8 bn the previous year, largely because of reductions in deficit contributions for a small number of companies,

- the highest DB contributions were the £1.65 bn paid by Royal Dutch Shell

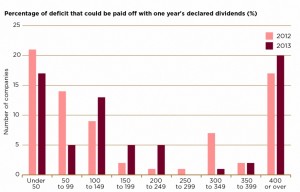

Contributions are lower than dividends

- five companies paid more into their pension schemes than they distributed in dividends, compared to eleven in 2012

- of the 68 FTSE 100 companies with a deficit, 22 had a deficit greater than the dividends paid out

- in 28 cases, the dividend was more than double the deficit suggesting that these companies could pay off their pension scheme deficit relatively easily if they wanted to

Discount rates

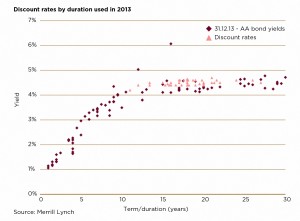

- the discount rate is used to calculate the present value of the projected pension benefits – a lower discount rate means a higher liabilities

- the discount rate should be based on “high quality” corporate bonds and the duration of the corporate bonds should be consistent with the estimated duration of the pension obligations

Inflation

- pension liabilities are also linked to price inflation – lower inflation leads to lower projected payments

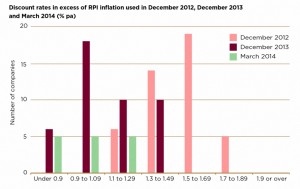

- The Bank of England publishes statistics for future price inflation implied by gilt spot rates – long-term RPI inflation implied by 20-year gilt spot rates was around 3.7% pa at the end of 2013

- for a typical company to justify an assumption much lower than this, a significant “inflation risk premium” would be needed ((This is the theoretical return that investors are willing to forgo when investing in index-linked gilts, in return for the inflation protection that these assets provide))

- in practice, it is the discount rate net of assumed future price inflation which is the key assumption

De-risking continued

There are three forms of de-risking:

- in a longevity swap, the pension scheme transfers the risk of its pensioners living longer than expected to an investment bank or insurance company, in return for an agreed stream of payments from the scheme

- in March 2014 Aviva did a £5bn longevity swap, and in July 2014 BT Group set up its own insurance company to resinsure 25% of its longevity risk (£16 bn)

- in a buy-out, the pension scheme pays a premium to an insurer, who takes on all responsibility and risks for paying the pensions to members

- InterContinental Hotels Group insured all of its pension liabilities in July 2013

- in a buy-in, the insurer makes the pension payments to the scheme which, in turn, pays the members

- the £3.6 bn ICI Pension Fund had a buy-in in 2014

- buy-in pricing was relatively attractive at the time of the report, allowing longevity risk to be transferred at little or no cost, as reflected in the number and size of transactions during the year

- reinsurers has significantly increased capacity for buy-ins and longevity swaps in recent years, and the UK is seen as the leading market for longevity risk transfers

- with UK-based insurers looking to make up for the decline in individual annuity sales following the new pension freedoms, pricing looked set to remain keen

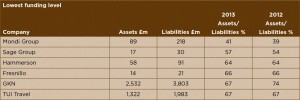

Alternatives to cash funding

- around 20% of FTSE 100 companies with DB schemes have used asset-backed contributions

- for example, International Airlines Group has provided security over aircraft and Whitbread has provided security over property

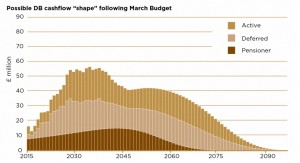

Impact of pension freedoms

- flexible access to DC pension schemes from April 2015 will likely impact DB schemes as retiring members transfer their benefits to DC schemes to take advantage

- this will potentially reduce company pension liabilities and deficits as the payment of a transfer value generally improves a scheme’s funding position

- it will also affect liquidity requirements (and hence investment strategy) as payments would be accelerated

- where a scheme is at risk of going bust, and falling into the PPF with its lower levels of compensation, there may be transfers out at all ages

Cash balance schemes

- the pension freedoms could revive interest in “cash balance” schemes, where employees receive a guaranteed cash pot at retirement, based on salary and length of employment

- pre-retirement investment risk is retained by the employer, with the

employee taking on all post retirement risk - before the pension freedoms, the main downside of these schemes was the employees’ risk that annuities would be expensive at the point of retirement

- now that pots can be taken as cash or put into drawdown, this is less of an issue

- Johnson Matthey, Morrisons and Diageo have cash balance schemes open to new employees

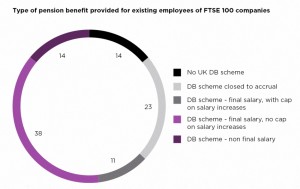

Continued move away from DB schemes

- GKN closed its “hybrid” scheme (a combination of DB and DC benefits) to new recruits

- this leaves only four FTSE 100 companies providing any form of DB pension to new employees – – Diageo, Johnson Matthey and Morrisons provide cash balance schemes, and Tesco provides a career

average revalued earnings (CARE) scheme

- BG Group, InterContinental Hotels Group, Sainsbury’s and Wolseley closed their DB schemes to future benefit accrual

- a further three companies, including HSBC and Severn Trent, reached agreement to do the same in the near future

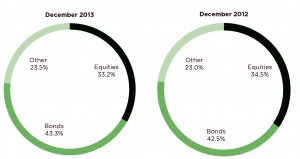

The flight from equities resumed

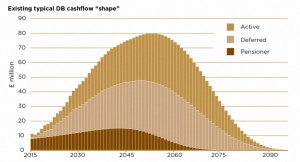

As pension schemes mature and the time horizon for payment of benefits decreases, companies and pension scheme trustees have typically looked to reduce the risks posed by the pension scheme.

- they do this by increasing their allocation to bonds relative to equities (despite that asset class being at the end of a 30-year bull market), in this period by an average 1.6%

- this is also during a time when equities significantly outperformed bonds, and so if no rebalancing had been undertaken, the equity allocation would have increased by 4%

- the previous year had seen an increase in the proportion of pension assets in equities

- some companies made more significant changes: BG Group moved 23% from equities to bonds; G4S increased its allocation to equities from 15% to 26%

- other companies such as Bunzl and Rexam, have pre-agreed “triggers” which switch assets from equities to bonds as the scheme funding level increases

- a continued move out of equities and into bonds is expected as funding positions improve

New inflation measure

RPIJ (on average 0.7% lower than RPI) is now a “National Statistic”. There are potential savings from switching to this measure of inflation – perhaps up to £20bn if all companies still using RPI switched to RPIJ

End of contracting out in 2016

The end of contracting out this will result in higher NICs for most employers with DB schemes. This may result in more closures of DB schemes.

Conclusions

- Pension liabilities are significant and deficits are increasing

- FTSE pension liabilities are 37% of market cap and deficits 4% of market cap (though they range as high as 25% of market cap)

- Contributions are falling and are lower than dividends

- 28 of the 68 FTSE companies with a deficit could clear their deficits easily from dividend payouts

- The new TPR objective of minimising impact on an company’s sustainable growth – though probably a good idea – will slow the clearing of deficits

- Passing pension risk to insurance companies remains attractively priced and is likely to continue

- Pension freedoms shouldreduce liabilities and deficits but will also present liquidity issues

- schemes at risk of going bust may see a rush of transfers out; this could improve the situation or bring things to a head

- Pension freedoms have made cash balance schemes more attractive, but whether the trend to pass all risk to the employee can be reversed is uncertain

- The increasing weighting to bonds is a potential time bomb as we are close to the end of a 30-year bull market in bonds

- The switch to RPIJ should reduce liabilities and deficits

- The end of contracting out may lead to the closure of more DB schemes

It seems doubtful that the current strategy of liability matching using bonds is the best solution in the present climate of low interest rates. A significant bond market correction is overdue and could greatly impact deficits.

With many pensions now having liability durations around the 20 year mark, a higher allocation to equities need not be risky. A valuation method using weighted average returns rather than bond yields would also be helpful.

Until next time.