Irregular Roundup, 27th November 2023

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup with soft landings.

Soft landings

After the good news on inflation earlier this month, John Authers looked at the chances of a soft landing.

- Most of us want to believe in a soft landing rather than a recession.

The difference has profound implications for the performance of bonds, and the degree that they correlate with stocks. If inflation falls without a big hit togrowth, then stocks will continue to have the wind at their back. In a hard landing, with negative growth and rate cuts, it would be time for bonds to beat stocks by a lot.

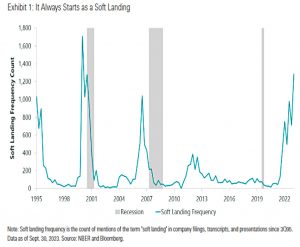

This chart from Jeff Schulze of ClearBridge Capital shows that recessions usually follow a spike in interest in soft landings.

- Hard landings look like soft landings to begin with.

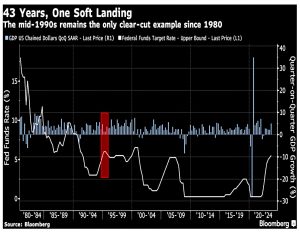

And soft landings are rare – we’ve had once since 1980 (in 1995, during a more growth-friendly period).

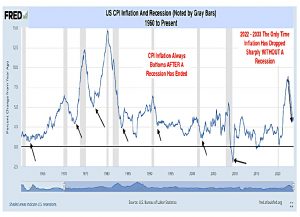

We’ve also never got inflation from 5% to 2% without a recession, though we have made it to 3%.

Immaculate soft landings have been rare. But massive global pandemics that shut down the economy and prompt the money supply to double in a month are even more rare. Maybe the Fed can achieve its 2% target without a downturn.

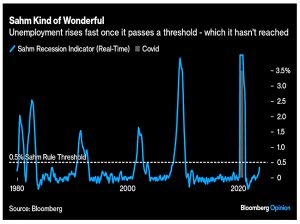

Next John looks at the Sahm rule:

Claudia Sahm posited that whenever the three-month rolling average rate of unemployment had gone up by at least 0.5 percentage points compared to its low for the previous 12 months, the economy was already in recession. Unemployment seldom rises a little and then stops.

We’re not quite there yet, but we’re getting close.

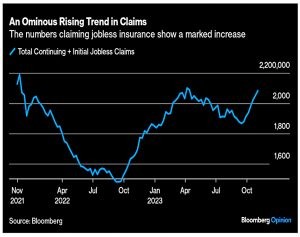

Unemployment claims are rising sharply, but are still lower than two years ago.

A source of optimism for John is the absence of geopolitical catalysts:

Downturns tend to have geopolitical triggers, from the Yom Kippur War and the Iranian crisis in the 1970s through to the first Gulf War and the Covid pandemic, or a spark that comes from the financial world — the Great Crash, the dot-com bubble, and the Global Financial Crisis being obvious examples.

We appear to have survived the invasion of Ukraine and the Hamas attack, as shown by the price of oil.

That said, the way oil — which took a dive Thursday — is behaving is worrying for the economy. Last year’s decline in price was achieved in part by a big drawdown of the US strategic petroleum reserve.

Another comfort is the Fed signalling:

Its latest “dot plot” didn’t predict 2% inflation until 2026, suggesting a long time to make the last step down to the target.

It’s also the case that the Presidential election in 2024 will mean the Fed is keen to avoid a recession.

- The danger is that this might lead to the return of inflation in 2025.

Tax evasion

It was Budget time in the UK last week, so a couple of articles from Joachim Klement on taxes caught my eye.

- The topic of the first was that tax evasion isn’t such a bad thing.

If people are able to cheat on their taxes and avoid paying them, they might work more because the additional income goes straight into their pockets. And that increase in work adds to GDP, which in turn increases employment, which in turn increases tax revenues.

If the increase in labour supply offsets the losses from tax evasion, the government in the end may be better off letting people cheat on taxes than enforcing 100% compliance.

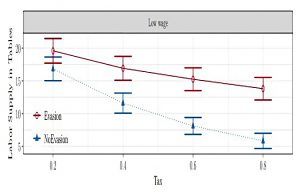

Joachim looked at a recent paper from Mill and Schneider (2023) which asked 1000 volunteers on Amazon MTurk to count the zeros in tables with 150 randomly allocated zeros and ones.

- This is boring work and the workers were only paid 12 cents per table; they also had to commit to a given number of tables before starting.

Tax was taken from their earnings at either 20%, 40%, 60% or 80%.

Some participants could put part of their income in a lottery where they had a 50% chance of not being taxed at all and a 50% chance of being audited. If they were audited, they had to pay the owed taxes and a 20% penalty.

So at the 20% tax rate, there is no incentive, but at the 80% rate, the expected gain is 30%.

It’s no surprise that on average people would do 37% more work.

- On average they tried to evade taxes on 40% to 50% of their earnings.

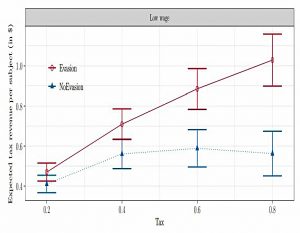

With a 50% audit detection rate plus a penalty when caught, tax receipts are higher than with no evasion.

- More interestingly, with no evasion, the 60% tax rate raises the most, but with evasion, an 80% tax rate raises even more.

Joachim accepts that the government can’t say “evade some tax”.

But what governments can do and indeed do all the time is provide tax loopholes that allow businesses and individuals to shelter some of their income from taxes or tax them at much lower rates.

These “loopholes” can raise more taxes because people work more than they would if all their money was taxed at their marginal rate.

Wealth taxes

The second article looked at wealth taxes.

- Like me, Joachim thinks that they are a bad idea.

Joachim used to live in Switzerland, where:

People regularly have their homes revalued to a lower level in order to save on wealth taxes. Once they want to sell their homes again, they call for a new valuation and their homes miraculously increase in value. A 1% decrease in wealth taxes leads to a 20% increase in house prices (after six years).

The problem is that wealth taxes apply to the entire value of an asset, not just its increase in value during the tax year.

Even a small wealth tax is equivalent to a large capital gains tax. Introducing a 3% wealth tax today [in the US] would be equivalent to raising capital gains taxes by 724%.

Apart from the revaluation of assets, wealth taxes have two other effects. First:

People will have a huge incentive not to invest in risky ventures anymore. If they are successful, they will face a massive tax bill.

For one thing, this means fewer small businesses and fewer jobs.

Small businesses have been responsible for roughly two out of three jobs created in the US between 2000 and 2021.

Secondly:

People who have large wealth would simply find ways to avoid paying these taxes on assets they own.

Joachim thinks this would mean higher salaries and more income tax, but I would just go and live in another country. It also means lower investment in businesses, as future growth would be taxed.

Managers and shareholders would have an incentive to rob the business blind and let it go under once they got their investment back.

A higher capital gains tax rate would work better than a wealth tax.

Argentina

John Authers also had a second interesting article, about the Argentine election result.

- The new president is libertarian economist (and TV star) Javier Milei who has campaigned on a platform of abolishing the central bank and switching from the peso to the US dollar.

Here’s a choice quote from Javier:

Central banks are divided in four categories: the bad ones, like the Federal Reserve, the very bad ones, like the ones in Latin America, the horribly bad ones,and the Central Bank of Argentina.

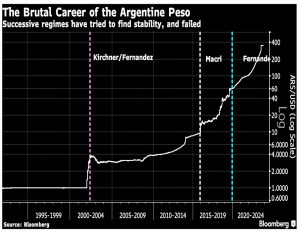

If you think that the UK is a nation in decline, take a look at Argentina.

The huge Irish, Italian and Jewish populations in Buenos Aires bear testament that at the turn of the last century, the city seemed as attractive as New York for migrants contemplating leaving Europe. In 1900, Argentina ranked 12th in the world by gross domestic product per capita.

Lots of things are responsible for the decline, but bad government is one of them, and Melei’s win shows that the population are fed up.

Dollarisation has already happened in Ecuador, Panama and El Salvador, but more interestingly its has already failed once in Argentina.

Throughout the 1990s, as the new democratic [governanment] attempted to align with the west, the peso was locked in a one-to-one exchange rate [with the dollar]. That policy collapsed amid political crisis in late 2001 as unemployment exceeded 20%.

The president fell and the peg to the dollar was removed, causing the peso to lose about two-thirds of its value almost instantly. Since that moment, Argentina has elected four presidents, who’ve all overseen sharp devaluations near the end of their terms.

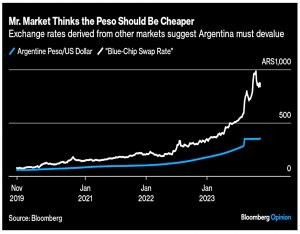

Twenty years later, the exchange rate is close to 400.

- Inflation remains above 100% pa.

The official exchange rate doesn’t tell the full story:

The “blue-chip swap” rate looks at the implicit exchange rate at which Argentine assets are bought and sold in financial markets.

This was the same as the official rate when President Macri left in 2019, but a big gap has opened up since.

John is not optimistic about Milei’s project:

The experience of the European countries like Greece that adopted the euro suggests that abolishing Argentina’s central bank would merely leave the country under monetary policy designed for someone else. Without devaluation as an option, the Greeks and others had to suffer through austerity and recession.

Quick Links

I have six for you this week, the first three from The Economist:

- The Economist said that Sam Altman’s return marks a new phase for OpenAI

- And that In Argentina Javier Milei faces an economic crisis

- And reported that Another crypto boss falls

- Alpha Architect said that a Focus on Income Can Undermine Returns

- Discipline Funds asked Is the S&P 500 Broken?

- And UK Dividend Stocks wondered Is HSBC a good choice for dividend investors?

Until next time.