Irregular Roundup, 4th December 2023

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup with inflation entrenchment.

Inflation entrenchment

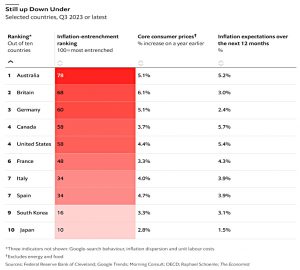

The Economist looked at what inflation-strugglers can learn from inflation-killers.

- America, Australia, Britain and Canada are lagging behind.

Across the OECD, consumer-price inflation fell from a peak of 10.7% in October 2022 to 6.2% in September. And wage growth is slowing. As a consequence, share prices are rising.

To see whether the word has really turned a corner, the newspaper calculated an inflation entrenchment score:

We have [looked] at core inflation, unit labour costs, “inflation dispersion”, inflation expectations and Google-search behaviour. We rank ten countries on each indicator, then combine the rankings.

The base news is that inflation could be more entrenched than when they first made the calculations back in 2022.

- The struggling (Anglophone) countries have a variety of problems – mainly high wage growth, and high consumer expectations of future inflation.

They are also the countries that provided 40% more stimulus during Covid.

- Their central banks also cut rates more than the rest.

High immigration is also inflationary in the short term.

There are also cultural issues:

Before covid, rich Asian countries had lived with low inflation for so long that it may have seemed a natural state of affairs. Therefore, following a jump in inflation in 2021-22, behaviour may have shifted in a disinflationary direction more quickly.

By contrast, in places like Britain, which experienced inflation surges in 2008, 2011 and 2017, people may have developed a more inflationary mindset.

Sentiment

Joachim Klement had a couple of articles on sentiment, the first dating back to February.

- He compared the intraday movements of the FTSE-350 over two nights in that month.

On 1st Feb:

The Federal Reserve decided to hike interest rates, but the communication was deemed so half-hearted that investors considered it a positive macro event and priced in less aggressive rate hikes and more rate cuts later in 2023.

The same thing happened again the next week.

In both instances markets opened higher in the morning due to the positive news from the US while the markets were closed at night. But the follow through during the day was different.

On 2 February, markets opened higher and then drifted higher throughout the day. On 8 February, markets opened higher but then gave back some of these gains as the day unfolded.

According to a recent study, the difference is market sentiment.

If sentiment was positive and overnight news is positive, markets open higher but tend to overshoot early in the day. As the day progresses, markets then drift lower to correct this overreaction and give back some of the gains.

Meanwhile, if sentiment is negative and overnight news is positive, markets open higher but then drift higher throughout the day because prices initially underreacted to the positive news.

Sentiment has the opposite effect when there is negative overnight news.

- Joachim notes that you can use the intraday moves to reverse-engineer the prevailing sentiment.

The second article applies these principles to individual stocks and their reactions to earnings news.

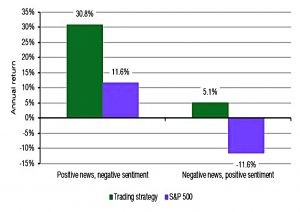

- Trading stocks on the day of the release would mean very high transaction costs, but a recent study looked instead at a holding period of 60 trading days (three calendar months).

The researchers used their own sentiment measure and bought stocks are soon as their earnings were announced.

If the earnings surprise is positive but market sentiment is in the bottom quartile, they buy the stock and hold it for 60 trading days or until sentiment has improved by one standard deviation, whatever comes first.

If the earnings surprise is negative and market sentiment is in the top quartile, they short the stock and buy it back after 60 trading days or after market sentiment has deteriorated by one standard deviation, whatever comes first.

This is using mean reversion in sentiment as a tailwind to the commonly observed post-earning announcement drift (in the direction of the earnings surprise).

The strategy works particularly well on the long side:

Buying stocks with a positive earnings surprise in a market depressed by negative sentiment is an excellent way to outperform.

On the other hand:

If market sentiment is optimistic, bad news simply is ignored and deteriorating sentiment is not enough to overcome the uplift from the days of positive market sentiment.

Investing whilst young

The Economist looked at how the young should invest.

- Begin early to give the magic of compounding time to work.

- Cut costs to stop that magic from being undone.

- Diversify.

- Do not try to time the market unless it is your job to do so.

- Stick to your strategy even when prices plummet and the sky seems to be falling in.

- Do not ruin it by chasing hot assets when the market is soaring, others are getting rich and you are getting jealous.

That’s a pretty good start.

- The problem is that future returns are likely to be lower than those of the recent past.

Global stock returns for 40 years to 2021 were 7.4% pa (real) compared with 4.3% pa for the previous 80 years,

- Bonds did even better – 6.3% against 0% for the earlier period.

Globalisation, low inflation and falling interest rates were the drivers.

- Over the whole 120 years, stocks return 5% and bonds just 1.7% (making the 60-40 return around 3.7%).

This means future investors can expect to end up with perhaps a third of the wealth of those of us lucky enough to invest over the last 40 years.

- Even worse, they might extrapolate those good recent returns and not save enough for the future.

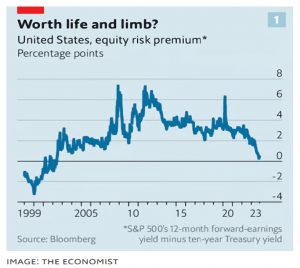

And to cap that, the good recent returns imply high valuation and even lower future returns than the average.

The equity risk premium, or the expected reward for investing in risky stocks over “safe” government bonds, has fallen to its lowest level in decades. Without improbably high and sustained earnings growth, the only possible outcomes are a significant crash in prices or years of disappointing returns.

Youngsters also hold too much cash (everyone does, but they are the worst).

Analysis of 7m retail accounts by Vanguard, found that the average portfolio for Generation Z (born after 1996) was 29% cash, compared with baby-boomers’ 19%.

But they do not like bonds.

They make up just 5% of the typical Gen Z portfolio, compared with 20% for baby-boomers.

These two effects will cancel each other out to some extent, but not entirely.

The third problem with young people’s investing style is “thematic investing”:

It is the practice of drumming up business byselling customised products in order to capture the latest market fad and flatter investors thatthey are canny enough to beat the market.

ESG used to be the flavour of the month but now it’s AI.

There are ETFs betting on volatility, cannabis stocks and against the positions taken by Jim Cramer.

We’re all guilty of this one – the trick is to limit it to a small part of your portfolio.

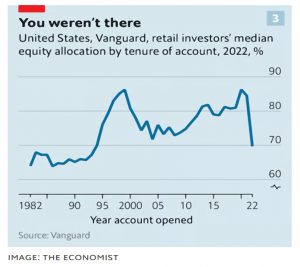

Vanguard also looked at how investors’ early market experiences shaped their behaviour:

Investors who opened accounts during a boom retain significantly higher equity allocations even decades later.

The median investor who started out in 1999, as the dotcom bubble swelled, still held 86% of their portfolio in stocks in 2022. For those who began in 2004, when memories of the bubble bursting were still fresh, the equivalent figure was just 72%.

This is bad news if it means that youngsters burned in 2020 and/or 2022 steer clear of the markets.

VCTs

There were few pieces of good news in the Autumn Statement last month, but one was the extension of the EIS and VCT sunset clauses from 2025 to 2035.

- I would have preferred the clauses to be abolished, but with Labour claiming to be in favour of the schemes, they will probably last long enough for my purposes.

In Ft Adviser, Tara O’Connor reported that VCTs are becoming more “evergreen”, by which she meant that people are investing before the traditional January to March rush.

- I have personally begun to invest as early as possible, after almost coming a cropper a few years ago when interest in VCTs saw a sudden upward spike.

Wealth Club reported that 38% of the tax-year total investment was raised by the calendar year end in 2019, but that this had risen to more than 50% in 2022.

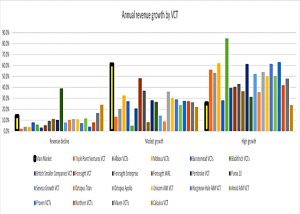

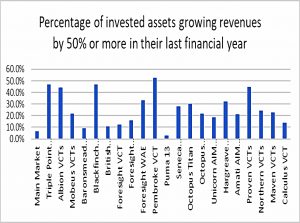

In IFA Magazine, Matt Williams reported that a quarter of VCT-backed British companies grew by 50% or more in the last year.

- The Wealth Club report also found that 48% of VCT investee companies had grown by more than 25% in a year.

The report covered 38 VCTs from 21 managers, representing 92% of the industry by value, with data for the year to June 2023.

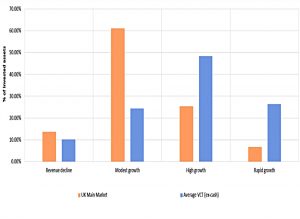

- The average VCT has 26% of its money in firms growing by more than 50%, compared to just 6.7% of the UK main market.

For Wealth Club, Nicholas Hyett said:

Venture Capital Trusts have had a tough couple of years, hit by a general sell-down in tech

stocks which has fed through to lower valuations for small, fast-growing companies. But the fall in net asset value masks some very strong performances from underlying

investments.Small businesses typically struggle most in an economic downturn, so the result might take some people by surprise. But the innovative, disruptive businesses that VCTs back behave a little differently. Because they’re taking market share from incumbents, or creating whole new services, they don’t rely on GDP growth to fuel expansion.

That could bode well for the next few years. From here on it’s successful revenue and profit growth that will determine the valuations for these small private businesses.

Quick Links

I have five for you this week, the first four from The Economist:

- The Economist explained that Charlie Munger was a lot more than Warren Buffett’s sidekick

- And invented us to Meet Constellation Software, tech’s Berkshire Hathaway

- And asked Is America’s EV revolution stalling?

- And said Short-sellers are endangered. That is bad news for markets.

- Alpha Architect looked at the After-Tax Performance of Actively Managed Funds.

Until next time.