Weekly Roundup, 24th January 2017

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup in The FT, with the Chart That Tells A Story. This week it was about investment styles.

Contents

Investment styles

Aime Williams looked at data from Numis Securities, who operate a small companies index covering the bottom 10% of the UK stockmarket.

- This makes it bigger than the FTSE SmallCap index (the bottom 4%)

- And smaller than the FTSE 250 index (the “middle” 15%)

Numis compared five styles of investing:

- Income

- Size (smaller stocks)

- Value

- Momentum

- Low-risk (low volatility, in fact)

Sadly they only looked at the results for the past year, rather than say the past decade.

- Momentum and low-volatility did badly

- Income investing did well

But I wouldn’t want to read too much into a single year’s data.

- The crash before Brexit, and subsequent recovery, plus the outperformance of resources stocks and the recent underperformance of bond proxies make 2016 an unusual year.

Perhaps the best conclusion to draw is that it’s usually safest to be diversified, even across styles.

DIY investors stay active

Aime’s second article was on DIY investors (specifically, clients of Hargreaves Lansdown, the largest retail broker) not holding any passive funds.

- 90% of HL’s customers had no trackers, despite them being cheaper and – on average – outperforming active funds

Hortense Bioy from Morningstar suggested that the best-buy lists provided by many brokers – such as HL’s Wealth 150 – may be to blame.

- For many years, passive funds didn’t appear on these lists (HL added them in 2016).

- The FCA’s recent study of asset managers found that only 7% of funds on best-buy lists were passives.

HL spokesman Laith Khalaf said that the passive funds had gone “from strength to strength”. ((Obviously this isn’t backed up by the data ))

- He expected closet trackers to suffer as they were replaced by real trackers in the future.

As well as the best-buy lists, the bigger marketing budgets of the more expensive active funds must be partly responsible.

- And before the Retail Distribution Review, larger up-front and trail commissions will have meant that active funds were more commonly recommended by advisers.

Not a Buffett fan

Merryn revealed that she’s not a Buffett fan, calling him “boring”.

- To be fair, she first said this back in 2005.

She confirmed her views again this week.

- She thinks Warren has abandoned his original true value investing style for a “quality growth” style like UK fund managers Neil Woodford and Nick Train.

Some would argue that there isn’t much difference between the two styles, and that growth investing is still about buying something that is cheap relative to future profits.

But not Merryn.

- For her, value investing is buying something at below fair value and selling when it gets back to fair value.

- Personally I would hang on a bit longer, to see whether the price momentum might cause the stock to overshoot fair value.

She sees buying cheap as the best way to add the famous “margin of safety” to your investments.

- At the moment, that approach inclines her towards Japan, where the average yield is 2.5% and dividend cover is more than 2.5 times.

- That compares with only 1.3 times for the top 10 yielding stocks in the FTSE-100.

- And 40% of Japanese stocks trade below book value (compared with 20% in the US and UK).

Industrial policy

In The Economist, Buttonwood worried about the return of industrial policy on both sides of the Atlantic.

- The concern was not that it would “pick winners” as is generally stated

- But rather that it would “cosset losers”, creating zombie companies that should really die

Protecting established firms at the cost of startups prevents the creative destruction by which capitalism produces productivity gains.

- “Total factor productivity” fell in 2015, and was flat in 2013 and 2014.

A new paper from the OECD showed that a 3.5% increase in the market share of zombie firms lead to a 1.2% decline in productivity.

- They defined zombies as firms older than 10 years with three successive years of interest cover (earnings over interest payments) of less than one.

In the short run, industrial policy, and zombie companies, can protect local jobs.

- But in the long run, reduced international competitiveness should mean that consumers (who include the protected workers) must pay higher prices or accept inferior quality goods.

Buttonwood also finds it funny that because the interventions are from right wing politicians (Trump and May), they are supporting stock markets.

- The same pledges from Bernie Sanders and Jeremy Corbyn would have the markets plunging.

Schumpeter looked at shareholder value.

- Most companies are run for the benefit of their shareholders, which means a focus on profit maximisation.

This traditional view of why firms exist dates back to a 1919 court ruling in the US, but only spread to Europe and Asia in the 1990s.

- But the rise of populist politics might mean that more people now want companies to pay higher wages, employ more people, pay more taxes and invest in their home countries.

The article came up with six flavours of shareholder value, from the fundamentalist to the state-owned corporation (like Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac in the US, who exist to make mortgages cheap, not to maximise profits).

- The second group along includes many Western firms, who look to long-term profit maximisation – Shell and Intel were the examples given.

- The third group tries to predict the laws of tomorrow, and voluntarily does what they may be required to do in future, in order to gain advantage over industry laggards – many energy and food companies fall into this group.

- The next group along are firms so profitable that sometimes they take a day off – Unilever and JP Morgan are examples here.

- The fifth and final group are corporate socialists, owned by families or dominant managers, or sometimes the stare – many non-western firms (such as China’s state firms that return around 7% on equity) are in this group, as is Goldman Sachs (which pays most of its profits to staff).

Populism will turn more companies into oracles, trying to predict what will be the law of tomorrow.

- But there is no need for a crisis of governance.

- The many flavours of shareholder value can cope.

Long term care

Over in MoneyWeek, Marina Gerner looked at how to pay for long-term care, a subject we looked at a couple of weeks ago.

- Full state funding for long-term care is withdrawn when your savings (including the value of your house) reach £14,250

- By £23,250 you have to meet all of the costs yourself (or get your relatives to)

And if you need care within six months of giving money away, the council can ask for the gift to be returned.

The average person in care needs four years of care at average of £600 to £700 a week.

- So that’s £120K to £140K in total.

- The best quality of care might cost £160K.

The government has pledged to introduce a cap of £72K for care costs, but this won’t arrive until 2020.

- The upper limit for state support will also rise, to £118K of assets.

Until then, the main options are to downsize or use equity release (if you have a property), or to buy an immediate care annuity.

- These annuities look terrible value – someone aged 85 would pay £108K to get £20K a year of care costs paid

Though I’ve not yet been directly affected by any of this, I’ve never understood why treatment for some illnesses (cancer for example) is completely free in the UK, whereas for others (dementia, say, or simple physical frailty) it is not.

- We need to level the playing field.

Lifetime ISA

The FT Adviser reported that some millennials are likely to “misuse” the new Lifetime ISA.

- Fintech firm Dunstan Thomas survey 1,000 people in their 20s and early 30s, and found that a third were interested in setting up a LISA.

- 25% were planning to use the LISA for retirement.

- 27% thought the LISA was more tax-efficient than a pension (it isn’t, especially compared to a workplace pension).

- 20% said they would opt-out of workplace pension auto-enrolment to fund the LISA.

The study also found that retirement saving was millennial’s fourth savings priority below a rainy-day fund, a holiday and a home.

- And more than 80% were confident that they would retire with a “sizeable” pension.

Clearly more education is in order, but given the small contribution limits (£4K pa), it’s unlikely to come from financial advisers.

Oxfam

And finally, Oxfam came out with its annual report on inequality, as reported in the Economist amongst other places.

- Operating more as a left-wing pressure group than a charity, Oxfam needed an attention-grabbing headline.

They settled on the idea that 8 billionaires are in total as rich as half of the world’s population.

- Using data from Forbes and Credit Suisse, Oxfam calculated that the billionaires own $426 bn of assets compared to the bottom half’s $409 bn.

- The Economist joked that the 8 could fit into a single minivan taxi at Davos.

There are three main criticisms of Oxfam’s report:

- By including 420M adults with net debts (assets of less than zero), they distort the picture

- most of these debtors live in rich countries (they may be former students, for example, or homeowners)

- you in fact have to be fairly lucky by global standards to borrow a significant amount of money, and you might have a high-ish income

- excluding those with negative wealth means that the bottom half of those left owns as much as the top 98 billionaires

- Wealth is converted to dollars at market rates, rather than using purchasing power parity (PPP).

- And using assets ignores the human capital that is the poor’s biggest asset

- the bottom half own only 0.15% of the world’s assets at market exchange rates

- but they have 11% of global income using PPP

- most studies of poverty use a measure such as PPP income of less than $2 per day

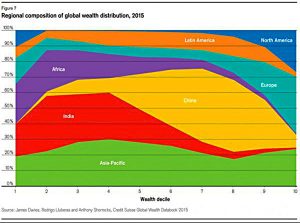

Oxfam’s own charts show that more of the very poor (as they define it) live in Europe and North America than in China:

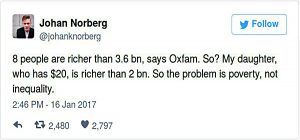

And including negative wealth meant that Johan Norberg could tweet that his daughter (with $20) is richer than 2bn people:

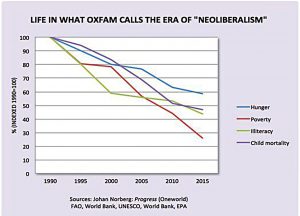

Oxfam wants to end what it calls “neoliberalism”, but as Norberg pointed out, neoliberalism seems to be working out quite well:

As Norberg says, the problem is not inequality, it’s poverty. It always is.

Until next time.

Thanks for the roundup Mike. Personally I think excessive poverty and inequality are both problems. Money = power and too much of either in the hands of a few individuals is probably not a good idea.

I don’t have any issue with inequality. I think equality is impossible to define (so that everyone agrees) and probably unachievable.

But my underlying point is that a focus on inequality (a la Oxfam) is likely to get in the way of fixing poverty.