Warren Buffett’s Annual Letters – 2012

Today we’re going to look at another of Warren Buffett’s Annual Letters, this time covering 2012.

Contents

Buffett’s Annual Letters

We’ve previously looked at Warren Buffett’s letters that cover 2014 and 2013. Today we’ll examine the 2012 letter, which was published in 2013.

I won’t repeat anything that we’ve come across before – as previously noted, there is a lot of overlap between the letters.

Performance

From 1965 to 2012, Berkshire Hathaway (BH) performance was as follows:

- Compounded annual gain:

- in BH book value per share: 19.7%

- in S&P 500 (dividends included): 9.4%

- difference in the two (BH excess gain): 10.3%

- Total gain for the period:

- in BH book value per share: 5,868 times

- in S&P 500 (dividends included): 74 times

Note that the BH share price isn’t being used as a performance measure.

The total gain for 2012 was $24.1 bn. Of this, $1.3 bn was used to repurchase BH stock, leaving a net gain of $22.8 bn.

The 14.4% gain for BH was slightly below the 16% gain in the S&P 500. This was the 9th time in 48 years that BH had underperformed. Eight of these years were years in which the S&P gained more than 15%.

BH has never had a 5 year period of underperformance, but a good performance from the S&P in 2013 might end that record. ((In fact, the S&P 500 gained 32.7% in 2013, against 18.2% for BH, so presumably this record is now broken – I can’t recall any mention of this fact in the 2013 report))

Warren pledges not to change benchmarks, whatever the results in 2013. ((It may not be coincidence however that in 2014 the BH share price – which has grown faster than the company’s book value – was introduced as another, and more favourable, comparator to the benchmark ))

2012 events

- Warren noted his disappointment at not being able to make a major acquisition in 2012, though by the time the report was published in 2013, he was able to report the purchase of 50% of Heinz.

- JP Lemann would head a Brazilian group of Brazilian investors who would own the other 50%.

- This purchase would cost BH $12 bn – $4 bn in equity and $8 bn in preferred shares with a 9% dividend. This would use up much of the cash generated in 2012.

- The “powerhouse five” delivered earnings of £10.1 bn.

- BH had a record year for “bolt-on” acquisitions, spending $2.3 bn on 26 companies. No BH shares were issued to fund these deals.

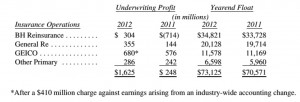

- The insurance companies provided $73 bn of float, and a $1.6 bn underwriting gain.

- Total employees increased by 17,604 to a record 288,462 – but staff at HQ remained at 24.

- Holdings in the “Big Four” non-subsidiary investments (American Express, Coca-Cola, IBM and Wells Fargo) were increased during the year

- BH now holds between 6% and 13.7% of these firms

- BH’s share of their annual earnings is now $3.9 bn

- BH’s has $26.7 bn of unrealised capital gains on their purchases of these companies

- BH invested a record $9.8 bn on plant and equipment, up 19% from the previous high of 2011

Insurance

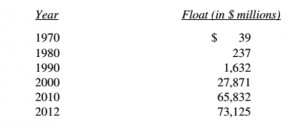

As usual, Warren stressed the importance of the ever-growing “float” of up-front cash from the insurance operations:

He remained concerned that the growth would soon go into reverse, but it hadn’t happened yet. Annual shrinkage of 2% was expected at some point in the future. ((In later reports, this forecast annual decline has been revised upwards to 3% a year ))

The insurance division recorded an underwriting profit for the 10th year running, with $18.6 bn of pre-tax gains over the period.

Warren noted that BH’s performance in exceptional – the industry as a whole has failed to cover claims plus expenses with its premiums in 37 of the previous 45 years.

Returns on tangible equity for insurance companies have been below the US average for decades. The decline in interest rates, and hence in returns on the bond portfolios held by insurance companies, would make things even worse in the future.

Regulated, Capital-Intensive businesses

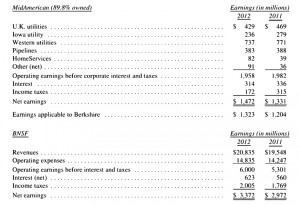

As previously noted, BNSF (railroad) and Mid American Energy invest heavily in long-life, regulated assets and have large amounts of long-term debt which does not need to be guaranteed by BH.

The inclusion of HomeServices, a real estate broker, in the MidAmerican numbers is an historical anomaly – MidAmerican already owned HomeServices when BH bought MidAmerican in 2000.

Manufacturing, Service and Retail

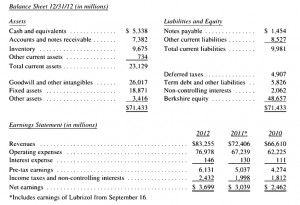

These figures are non-GAAP and exclude amortization of intangibles; Warren and Charlie believe this more accurately reflects the expenses and profits of the businesses.

The companies in this group earned 16.3% after tax on $22.6 bn of net tangible assets.

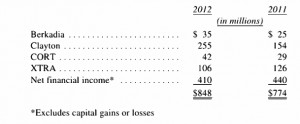

Financials

This is the smallest section of the BH breakdown, and includes rentals of trailers (XTRA) and furniture (CORT) plus Clayton Homes – the US’s largest home builder – and it’s $13.7bn mortgage portfolio.

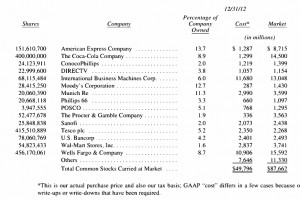

Investments

For the first time, this list includes a stock that was not bought by Warren himself. ((In the sense that he did not make the decision to buy it for BH))

From 2012 onwards, investments made by Todd Combs and Ted Weschler – BH’s new investment managers – will be included here if they are valued at $1 bn or more.

The first such stock is DIRECTV, which both Todd and Ted hold in their portfolios and whose combined holdings at the end of 2012 were valued at $1.15 billion.

In 2012 both Todd and Ted outperformed the S&P 500 by double-digit margins, and also did much better than Warren’s own investments. As a result, they now each manage almost $5 billion of BH money in total.

These figures include the money from the pension funds of some BH subsidiaries; others must be managed by outside advisers for regulatory reasons. Holdings of the pension funds are not included in the BH annual report, though the portfolios often overlap.

Derivatives portfolio

The BH derivatives portfolio is being wound down, as new commitments would require collateral and Warren and Charlie prefer to operate without calls on the BH cash pile. This reduces returns in the good years but will ensure that BH survives a once in a century crash.

The derivatives sold to offer credit protection on corporate bonds will expire in the next year with a projected profit of $1 bn. There has also been an average float of $2 bn over their five-year lives.

BH also sold puts on the stock indices of the US, UK, Europe and Japan during 2004 and 2008, producing upfront premiums of $4.7 bn. In 2010, around 10% of the portfolio was closed at a profit of $222M.

The remainder expire between 2018 and 2026. At the end of 2012 they are showing a $0.3 bn profit, a big improvement from the nominal $2 bn loss at the end of 2010.

Newspapers

BH bought 28 daily newspapers for $344M over the previous 15 months. This is surprising for two reasons:

- Warren has long stated that the circulation, advertising and profits of the newspaper industry are certain to decline

- The newspapers are too small to qualify under BH’s regularly stated acquisition requirements – they won’t “shift the needle”

Warren’s explanation for the second point is simple, if unsatisfactory – he and Charlie “love newspapers”.

His explanation for the first involved the history of American newspapers. We’ll pick it up at the point where newspapers were very profitable because of a local monopoly, and almost all US cities became one-newspaper towns, or had two competing papers run from the same stable.

This was because most people want to read (and pay for) only one paper. The paper with the biggest circulation got all the local advertising. Ads drew in more readers, and more readers drew in more ads – “survival of the fattest”.

The internet has changed all this. Stock quotes and sports news are consumed live, not the next day. People look for jobs and homes online. And TV dominates current affairs.

But papers are still good for local news (according to Warren). ((I suspect this may be an US phenomenon – local papers in the UK are now mostly free-sheets that barely last the commute home ))

Warren notes that the Wall Street Journal has operated a pay wall for its content online for years. Apparently so has the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, and this has worked well over the past decade.

Warren and Charlie believe that daily locals serving tightly bound communities and having a “sensible” internet strategy (ie. charging for content) will do well. I can’t say I agree with him – at the time of writing even Pay TV looks to be doomed, never mind papers. ((Having said that, I doubt I would have bought a railway either, had I been in the position to do so ))

They plan to buy more papers if they can find them at appropriate prices (ie. a very low multiple of earnings).

Dividends

Under pressure from friends and shareholders, Warren explained why BH doesn’t pay dividends, even though Warren loves the dividends he receives from the non-subsidiary investments BH owns.

- Warren believes that companies should first look to allocate earnings into reinvestment in the existing business that will “widen the moat” – improve efficiency, expand territory, or extend and improve product lines.

- In 2012 BH spent a record $12.1 bn on fixed-asset investments and bolt-on acquisitions.

- The next step is to look for unrelated acquisitions.

- BH’s track record here is “satisfactory”, but the current size of BH means that making sensible and meaningful (ie. large) purchases is harder than before.

- The third use of funds is to repurchase shares when they sell at a meaningful (20%) discount to intrinsic value.

- BH originally used a limit of 110% of book value, but have since increased this to 120% of book.

Which leaves dividends.

Warren imagines that he and I share a $2M net worth business that earns 12% pa on net worth now and on reinvested earnings, and that outsiders will buy shares of at 125% of net worth.

So we each own a $1.25M holding, and our $1M of net worth generates $120K of earnings each year.

I say to Warren that we should distribute one-third of our earnings, and re-invest two-thirds. This means that the company (its stock value and the dividends it pays out) are now growing at 8% a year – the 12% earned minus the 4% dividend that is paid out.

After 10 years the company is paying each of us $86K in dividends and is worth a total of $4.32M. We each own shares worth $2.7M (at the 125% rating).

As an alternative, we could sell 3.2% of our shares, which would produce $40K in the first year (at the 125% valuation); this figure would grow each year.

But what we still own of the company is now growing at 12% pa, rather than 8%.

Under what Warren calls the “sell-off” scenario, after 10 years the company is worth $6.21M. We each own 36.12% of the business, a net worth of $2.24M.

Our shares are worth $2.8M (at the 125% rating), around 4% more than the dividend approach produces.

Similarly, the annual cash receipts from selling 3.2% of our shares will now produce 4% more than the dividends.

All that is needed for “sell-off” to work is the 12% annual earnings and 125% share valuation of net worth.

Both conditions are more than satisfied for the S&P 500. The more they are exceeded, the greater the advantage of the sell-off policy.

There are two further benfits from “sell-off”:

- dividends impose a particular distribution percentage, and those who want more or less are thwarted

- those still in the wealth accumulation phase should logically want no dividend at all

- there are often tax disadvantages to dividends in the US

If the book-value build up and the market-price premium disappear, Warren pledges to re-examine the policy.

Some quotes to end with

Too much of a good thing can be wonderful. (Mae West)

It is far better to buy a wonderful business at a fair price than to buy a fair business at a wonderful price. (Charlie Munger)

I owe my exalted position in life to two great American institutions – nepotism and monopoly. (Southern newspaper publisher)

There is nothing quotable from Warren himself this year.

Lessons for BH and the private investor

I’m afraid I found nothing new in this year’s report apart from the explanation of the dividend policy:

- With 12% annual earnings and shares valued at 125% of net worth, a “sell-off” approach (at 3.2% pa) beats a dividend distribution of 4%. As long as these conditions persist, BH won’t issue dividends.

I hope the lack of new material for the year proves to be an exception and not the rule.

Until next time.

This post is one of a series on the Warren Buffet Annual Letters. To read the other summaries, go to the Warren Buffet Quotes and Annual Letters page.

1 Response

[…] previously looked at Warren Buffett’s letters that cover 2014, 2013, 2012, 2011 and 2010. Today we’ll examine the 2009 letter, which was published […]