Warren Buffett’s Annual Letters – 2009

Today we’re going to look at another of Warren Buffett’s Annual Letters, this time covering 2009.

Contents

- Buffett’s Annual Letters

- Performance

- The way BH do things

- Insurance

- Regulated Utility Business

- Manufacturing, Service and Retailing Operations

- Finance and Financial Products

- Investments

- Derivatives

- Risk control and the banks

- Buying with shares

- More quotes from Warren

- Quotes from other people

- Lessons for BH

- Lessons for the Private Investor

Buffett’s Annual Letters

We’ve previously looked at Warren Buffett’s letters that cover 2014, 2013, 2012, 2011 and 2010. Today we’ll examine the 2009 letter, which was published in 2010.

I won’t repeat anything that we’ve come across before – there is always a lot of overlap between the letters.

Performance

From 1965 to 2009, Berkshire Hathaway (BH) performance was as follows:

- Compounded annual gain:

- in BH book value per share: 20.3%

- in S&P 500 (dividends included): 9.3%

- difference in the two (BH excess gain): 11.0%

- Total gain for the period:

- in BH book value per share: 4,341 times

- in S&P 500 (dividends included): 54 times

The BH share price compounded annually at 22% over the same period, and the total gain was 8,015 times.

In 2009 the gain for BH was 19.8%, somewhat less than the S&P 500’s 26.5%. The gain in net worth during 2009 was $21.8 bn.

The way BH do things

Warren ran through a few things that BH would and wouldn’t be getting up to.

- BH don’t buy businesses whose futures they can’t evaluate, no matter how exciting the growth prospects.

- Autos, aircraft and television sets were each once “no brainer” industries, but competition within them meant that few companies prospered.

- Being able to clearly see dramatic growth for an industry does not mean BH can judge what its profit margins and returns on capital will be.

- BH will stick to businesses whose profits seem reasonably predictable for decades.

- BH will always be liquid – they keep $20 bn plus of cash-equivalents.

- In September 2008, BH was a supplier of liquidity and capital to the system, to the tune of $15.5 bn.

- $9 billion went to bolster capital at three “highly regarded and previously secure businesses that needed a vote of confidence”

- The remaining $6.5 bn satisfied a commitment to help fund the purchase of Wrigley.

- BH lets its subsidiaries operate on their own, without supervising and monitoring them to any degree.

- That means they are sometimes late in spotting management problems and that both operating and capital decisions are occasionally made with which Charlie and Warren would have disagreed.

- They would rather suffer the visible costs of a few bad decisions than incur the many invisible costs from decisions made slowly or not at all because of a bureaucracy.

- BH makes no attempt to woo Wall Street.

- Warren doesn’t want investors who buy and sell based upon media or analyst commentary.

- He wants partners who wish to make a long-term investment in a business they understand, which follows policies with which they concur.

Insurance

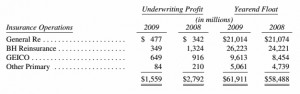

The insurance float is now $62 bn.

The insurance operations have returned an underwriting profit for seven consecutive years.

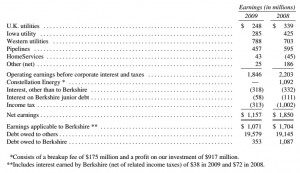

Regulated Utility Business

BH’s regulated electric utilities, usually acting as monopolies, operate in symbiosis with their customers:

- users depend on BH to provide first-class service and invest for their future needs

- permit and construction periods for generation and transmission facilities mean that BH have to be far-sighted

- BH in turn look to regulators to allow an appropriate return on the huge amounts of capital that must be invested to meet future needs

In the early days, Charlie and Warren shunned capital-intensive businesses.

The best businesses by far are those with high returns on capital that require little additional investment to grow.

But now that BH generates ever-increasing amounts of cash, they are willing to enter businesses that regularly require large capital expenditures, if they have reasonable expectations of earning decent returns.

BH sees a “social compact” between the public and their railroad business, just as with utilities. If either side shirks its obligations, both sides will suffer.

In the future, BNSF results will be included in this “regulated utility” section.

Manufacturing, Service and Retailing Operations

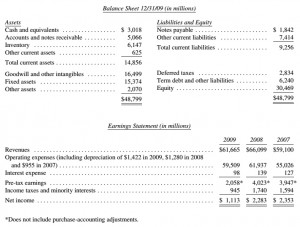

Most of the operations in this sector suffered in 2009’s severe recession. The major exception was McLane, the distributor of groceries, confections and non-food items to retail outlets including Wal-Mart, which had record pre-tax earnings.

The major problem for BH in 2009 was NetJets, which offers fractional ownership of jets.

It is the premier company in its industry, but has recorded an aggregate pre-tax loss of $157M over 11 years of BH ownership. In the same period, debt has soared from $102M at the time of purchase to $1.9 bn.

Dave Sokol, the manager of Mid-American Energy, was moved across in August 2009 to sort things out, and the company is already profitable. Debt has been reduced to $1.4 bn.

Warren and Dave have strong personal interests here, since they and their families use NetJets for almost all of our flying.

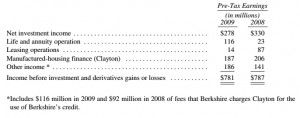

Finance and Financial Products

The largest firm in this section is Clayton Homes, number one US producer of modular and manufactured homes.

Unfortunately, industry output has fallen from 382,000 units in 1999 to 60,000 units in 2009.

Total US housing starts in 2009 were 554K, by far the lowest number in the past 50 years. A few years earlier, starts were 2M annually.

But household formations (demand) was only 1.2M pa, so the US ended up with far too many houses. Reducing housing starts is the only realistic way of fixing this.

Within a year or so residential housing problems should largely be behind us.

A second problem for Clayton is a differential in mortgage rates between factory-built homes and site-built homes.

FHA, Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae mortgages can be securitized and converted into something close to a US government underwritten debt.

Site built homes can therefore be borrowed against at 5¼%. Buyers of factory-built home have to pay around 9%.

Clayton’s delinquencies and defaults remain reasonable despite the low-income client base. Their loans payments are linked to verified incomes (they aren’t “liar’s loans”).

Warren worries that if the government qualifications aren’t broadened, the manufactured-home industry will struggle and dwindle.

At the end of 2009, BH became a 50% owner of Berkadia Commercial Mortgage (formerly Capmark), the country’s third-largest servicer of commercial mortgages, with a $235 billion portfolio.

BH’s partner is Leucadia, who they previously teamed with to buy Finova, a troubled finance business.

Investments

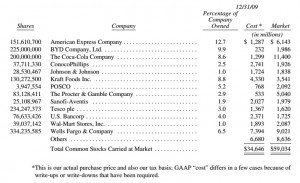

The table show investments valued at greater than $1 bn.

In addition, BH owns positions in non-traded securities of Dow Chemical, General Electric, Goldman Sachs, Swiss Re and Wrigley with an aggregate cost of $21.1 bn and a carrying value of $26.0 bn.

These positions were all purchased in the last 18 months. They deliver $2.1 bn annually in dividends and interest.

At year end, BH also owned 22.5% of BNSF, but they now own the entire company.

The largest sales of 2009 were in ConocoPhillips, Moody’s, Procter & Gamble and Johnson & Johnson. These were made early in 2009 to raise cash for the Dow and Swiss Re purchases and late in the year to fund the BNSF purchase.

Warren reminds us that in the 2008 report he noted the unusual conditions in the corporate and municipal bond markets. These bonds were very cheap relative to US Treasuries. Warren bought some, but wished he had bought more.

BH began 2008 with $44.3 bn of cash-equivalents, and have since retained operating earnings of $17 bn.

After significant investments, cash at year-end 2009 is down to $30.6 billion (with $8 billion of this earmarked for the BNSF acquisition).

Derivatives

A few things have changed since the extensive coverage in the 2008 letter:

- Some credit contracts have run off

- The terms of about 10% of our equity put contracts have changed – maturities have been shortened and strike prices reduced (with no money changing hands)

Warren still expects the contracts to deliver a profit over their lifetime, even excluding the investment income on their $6.3 bn float.

Only a handful of the contracts require collateral to be posted; the total requirement has never exceeded $1.7 bn.

The carrying value of the contracts will vary significantly, which can affect reported quarterly earnings, but not cash or investment holdings.

Risk control and the banks

Charlie and Warren believe that a CEO must not delegate risk control, because it’s too important.

If BH ever gets in trouble, it will be Warren’s fault, and not that of a Risk Committee or Chief Risk Officer.

With this in mind Warren thinks that the CEOs and directors of bailed-out financial institutions have been very lucky to escape unscathed.

The BNSF deal has required BH to issue an additional 6.1% of shares.

Warren and Charlie don’t like to do this because they can’t exchange an undervalued stock (BH) for a fully valued one without hurting the existing shareholders.

Warren illustrates this with an example:

- Company A and Company B are the same size and both are intrinsically worth $100 per share, but trade at $80 per share.

- The CEO of A offers 1¼ shares of A for each share of B.

- He correctly tells his directors that B is worth $100 per share, but fails to explain that he is paying $125 of intrinsic value in A for it.

Warren says he has been in many such meetings, and it is always explained why the company being acquired is worth more than its market value, but the intrinsic value of the acquirer is never mentioned.

It is always assumed to match the market price exactly, even though if a bid came in at that price, it would be immediately rejected.

Warren recommends – perhaps jokingly – hiring a second deal adviser to argue against any proposed acquisition.

If Warren’s hypothetical deal went through, the shareholders of B would end up owning 55.6% of the combined company.

The CEO of A might still come out ahead, assuming he was chosen as the CEO of a company now twice as large, with associated increases in prestige and compensation.

When the acquirer’s stock is overvalued, things work the other way.

That’s why bubbles lead to extra stock being issued.

Unfortunately, the BNSF acquisition included 40% BH shares, worth more than their market value. After taking account of BH’s existing holding, around 30% was bought in shares.

In the end, the downside of this was outweighed by the chance to deploy $22 billion of cash in a business BH understood and liked for the long term.

But it was a close-run thing.

More quotes from Warren

There are three quotes that we haven’t already included above:

When it’s raining gold, reach for a bucket, not a thimble.

A climate of fear is the investor’s best friend.

Don’t ask the barber whether you need a haircut.

Quotes from other people

All I want to know is where I’m going to die, so I’ll never go there. (Charlie Munger)

Are we supposed to applaud because the dog that fouls our lawn is a Chihuahua rather than a Saint Bernard? (Charlie Munger)

Customer: Thanks for putting me in XYZ stock at 5. I hear it’s up to 18. Broker: Yes, and in fact, the company is doing so well now, it’s an even better buy at 18 than it was at 5. Customer: Damn, I knew I should have waited. (Old Wall Street joke)

Lessons for BH

- BH don’t buy businesses whose futures they can’t evaluate, no matter how exciting the growth prospects.

- BH lets its subsidiaries operate on their own, without supervising and monitoring them to any degree.

- BH makes no attempt to woo Wall Street.

- A CEO must not delegate risk control, because it’s too important.

Lessons for the Private Investor

- A growing industry or sector doesn’t necessarily mean growing and profitable firms with rising share prices.

- Predictable profits are more important than being in a growth sector.

- An acquisition funded by issuing shares in an undervalued stock is likely to hurt the existing shareholders, especially if the target company is fully valued.

Until next time.

This post is one of a series on the Warren Buffet Annual Letters. To read the other summaries, go to the Warren Buffet Quotes and Annual Letters page.