Warren Buffett’s Annual Letters – 2019

As part of our series on Warren Buffett’s Annual Letters, we look at the letter for 2018, which was released over the weekend.

Contents

Warren Buffett’s Annual Letters – 2019

We’ve previously looked at Warren Buffett’s letters that cover:

2018, 2017, 2016, 2015, 2014, 2013, 2012, 2011, 2010, 2009 and 2008.

Today we’ll examine the 2019 letter, which was published over the weekend.

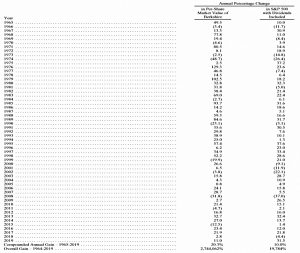

Performance

Over the 55 years to 2018, BRK has compounded its share price by 20.3% pa.

- Growth in book value is no longer presented.

During the same period, the S&P 500 has compounded at 10.0% pa (dividends included).

- Total gains are 2.7M% for BRK and 19.7K% for the S&P – more than a thousandfold difference.

But in 2019, BRK was up only 11% whilst the S&P went up 31.5% including dividends.

- This is the biggest shortfall in a decade.

Under GAAP rules, BRK earned $81.0 bn in 2019 (up from just $4bn the previous year):

- $24 bn in operating earnings (down 3%)

- $3.7 bn capital gains on sales of investments

- and $53.7 bn in gains from unrealised capital gains on investments (“mark to market”).

Warren doesn’t believe the inclusion of the last line (new since 2018) to be sensible since there will be large swings in profits from market movements.

Charlie and I urge you to focus on operating earnings – which were little changed in 2019 – and to ignore both quarterly and annual gains or losses from investments, whether these are realized or unrealized.

I don’t have a problem with the change personally – BRK has investments, and they fluctuate in value.

- Updating the market price once a year seems fine, but perhaps not for quarterly statements.

And it isn’t really income, which is Warren’s real point.

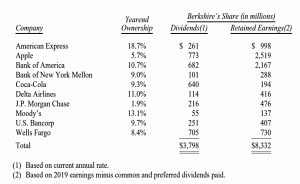

Retained earnings

In the next section, Warren stresses the importance of compounded retained earings for long-term growth and explains the different treatment of these earnings in the two categories of company that BRK owns:

In our controlled companies, the earnings of each business flow directly into the operating earnings that we report to you. What you see is what you get.

In the non-controlled companies, only the dividends that Berkshire receives are recorded in the operating earnings we report. The retained earnings? They’re working hard and creating much added value, but not in a way that deposits those gains directly into Berkshire’s reported earnings.

Unusually, for BRK this is a big deal – the invisible earnings are $8.3 bn for the top 10 holdings alone:

Bad acquisitions

Warren notes that the impact of purchasing poor businesses diminishes over time:

As the years pass, the “poor” business tends to stagnate, thereupon entering a state in which its operations require an ever-smaller percentage of Berkshire’s capital. The assets employed at Berkshire’s winners gradually become an expanding portion of our total capital.

He uses the original Berkshire textile business as an example.

Self-insurance

Non-insurance businesses earned $17.7 bn in 2019, up 3%.

A fire at a French plant owned by oil additive subsidiary Lubrizol was covered by insurance, but unfortunately, that insurance was taken out from a Berkshire company.

In Matthew 6:3, the Bible instructs us to “Let not the left hand know what the right hand doeth.” Your chairman has clearly behaved as ordered.

It’s a neat joke, but I’m still a fan of self-insurance.

- In the long run, you should come out ahead roughly to the tune of the insurance company’s profits.

Float

BRK’s enormous insurance operation only averages $1.6 bn in profits per year, and in 2019 it only earned $400 M.

But it does provide the float, which is now up to $129 bn:

Warren notes that the float earns much less than it used to, (for all insurance companies) because of low interest rates:

Where once these insurers could safely earn 5 cents or 6 cents on each dollar of float, they now take in only 2 cents or 3 cents.

And that’s if they are lucky enough to be based in the US – many bond yields are negative.

Green energy

Warren points out that BRK’s energy subsidiary now makes good use of wind power.

In 2021, we expect BHE’s operation to generate about 25.2 million megawatt-hours of electricity (MWh) in Iowa from wind turbines that it both owns and operates. That output will totally cover the annual needs of its Iowa customers, which run to about 24.6 million MWh.

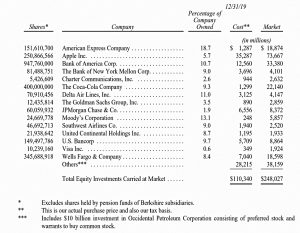

Investments

BRK’s investments are now worth $248 bn.

- Note that Kraft Heinz is excluded from this list because BRK is part of the control group, which means they need to account for the holding via the “equity method”.

What we see in our holdings is an assembly of companies that are earning more than 20% on the net tangible equity capital required to run their businesses. These companies also earn their profits without employing excessive levels of debt.

Warren contrasts these returns with the 2.5% or less available from Treasuries.

If something close to current rates should prevail over the coming decades and if corporate tax rates also remain near the low level businesses now enjoy, it is almost certain that equities will over time perform far better than long-term, fixed-rate debt instruments.

So Warren doesn’t think the public market is too expensive.

- Although in another way, he does, because once again BRK didn’t make any acquisitions.

Which also means that he thinks the same of the private market.

The road ahead

As expected, Warren touched on succession planning:

Charlie and I long ago entered the urgent zone [for supplying biographical information to newspaper obituary departments]. That’s not exactly great news for us. But Berkshire shareholders need not worry: Your company is 100% prepared for our departure.

He outlines five reasons for this, but the thing that investors are interested in is who will take over (not stated).

- Later in the letter, Warren says that Greg Abel, 57, and Ajit Jain, 68, (both vice chairmen of BRK) will be added to the question-answering panel at the AGM – alongside Warren and Charlie Munger.

Warren also explains his will:

The will goes on to instruct the executors – and, in time, the trustees – to each year convert a portion of my A shares into B shares and then distribute the Bs to various foundations. Those foundations will be required to deploy their grants promptly. In all, I estimate that it will take 12 to 15 years for the entirety of the Berkshire shares I hold at my death to move into the market.

Which is obviously good news for the share price.

Independent directors

In the next section, Warren rails against the logic of classifying non-wealthy directors (“NWDs”) as independent, whilst those with a stake in the company are deemed to be lacking in independence.

Is it any wonder that a non-wealthy director hopes – or even yearns – to be asked to join a

second board, thereby vaulting into the $500,000-600,000 class? The CEO of a company searching for board members will almost certainly check with the NWD’s current CEO as to whether NWD is a “good” director. “If the NWD has seriously challenged his/her present CEO’s compensation or acquisition dreams, his or her candidacy will silently die. When seeking directors, CEOs don’t look for pit bulls. It’s the cocker spaniel that gets taken home.

Warren thinks that directors should have skin in the game:

Not long ago, I looked at the proxy material of a large American company and found that eight directors had never purchased a share of the company’s stock using their own money. (They, of course, had received grants of stock as a supplement to their generous cash compensation.)

Stock repurchases

BRK spent $5 bn in 2019 repurchasing about 1% of the company’s shares.

Conclusions

It’s a fairly short and quiet letter again this year.

- It’s been four years since the last major acquisition (Precision Castparts in 2016), and BRK has $128 bn in cash.

There was no mention of the sale of BRK’s newspaper holdings – though admittedly this was announced in January 2020.

- And the big writedown of Kraft Heinz was ignored.

Maybe we’ll hear more about the next big deal – and more about succession planning – in the 2020 letter.

- Until next time.