Weekly Roundup, 11th October 2021

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup with a look at stock markets.

Stockmarkets

The Economist had three articles about stock markets. The first was about the decline of the London market.

In 2006 the companies with shares listed in London were worth 10.4% of the global equity market. Today, that figure is 3.6%. Its share of Europe’s total market value has declined from 36% to 22%.

Perhaps more worryingly:

Less than one-fiftieth of the FTSE 100’s value comes from tech companies, compared with almost 40% of the S&P 500 index of American firms.

The newspaper blames UK managers for the poor performance of the largest UK firms, together with a lack of governance from the asset management industry.

- And UK pension funds prefer bonds for their “lower risk”.

Big firms are relocating to other territories, reversing the impact of the Big Bang deregulation in 1986.

- And only 4% of startups choose London for their IPO (down from 20% in 2005).

The one bright spot is venture capital:

Britain has 34 privately held startups worth over $1bn and has created more such unicorns than France, Germany and Sweden combined.

The Economist has several suggestions:

- cull the pool of 3000+ non-executive directors

- allow dual-class listings to encourage founders who want to retain control

- make it easier for startups to hire talented foreigners

- merge Britain’s 5,327 corporate pension schemes into a few giants, and incentivise them to buy equities rather than bonds

That all sounds good to me.

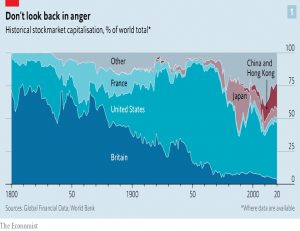

The second article attempted to put the UK market’s decline into a broader historical context.

Britain’s is hardly the only one to have ballooned and shrivelled in the centuries since the idea of raising capital by selling equity to the public gained popularity. The fortunes of the world’s big exchanges have fluctuated throughout history.

Today’s trends are tech and Asia.

- But in the 19th century, we had canals, Latin America and railways (first in Europe, then the US).

After the World Wars, the US took over from Europe.

During the fighting bourses had largely been shuttered. When exchanges were able to open, they had frequently been subject to price restrictions that limited trading.

Currencies were devalued and capital controls imposed, complicating cross-border flows. Hyperinflation in Germany and much of eastern Europe, combined with the rise of communism, had wiped out many investors.

As globalisation grew, so did Japan’s market, which reached close to 50% of the global market cap in 1989.

- As Japan declined, China and Hong Kong took its place.

America has so far seen 750 IPOs in 2021, for companies with a total value of $242bn. China has 427, for companies worth $72bn. France, Germany, the Netherlands and Britain [have a] combined value of just $45bn.

And as the chart shows, China and America have a much higher tech weighting.

The third article looked at US IPOs and SPACs.

Last year a record number of companies listed via reverse mergers with special-purpose acquisition companies (SPACs).

A standard IPO is run by banks, which pocket 7% of the money raised as fees.

- They strike a balance between the high price desired by founders and the low price wanted by institutional investors, aiming to achieve the first day “pop” in price (which averaged 21% over the last decade).

The use of SPACs and direct listings is now exerting downward price pressure on fees, and 180-day lockups on sales by founders are becoming staggered.

- Similarly, direct listings are now allowed to raise extra capital at the point of listing.

Meanwhile, SPAC fever has broken after a run of losses:

New SPACs that had merged with their target by mid-February have lost a quarter of their combined market capitalisation since then, wiping out $75bn in shareholder value.

The SEC is worried that SPACs mostly benefit founders, who take 20% of the shares (although this share is now starting to shrink).

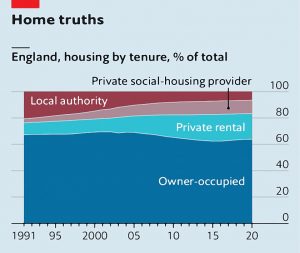

Housing

The Economist also reported that the government is about to ditch its ambitious housebuilding target.

- The target is 300K homes per year, and the plan was to simplify the planning process to achieve this, notably by reducing the ability of locals to object to new developments.

Then came the Chesham and Amersham by-election loss to the Lib Dems, who surprisingly became NIMBYs for the purpose of winning the seat.

- The whisper is that instead of planning changes, the Tory party conference will announce yet more support for first-time buyer mortgages.

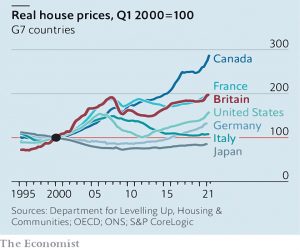

Houses in the UK are expensive, at eight times median earnings (( My own first property bought way back in 1987, was seven times median earnings, but I was buying in outer London ))

- A consensus has developed that supply is the problem, but in reality, low interest rates are probably to blame.

There probably is a shortage of homes (at least in the places that people want to live), but building just 300K homes a year will take a long time to fix this since the existing pool of properties is 28.1M.

- 300K is just 1% of that total, and won’t impact prices.

In any case, some properties are also converted to flats each year and the net creation of dwellings has apparently exceeded the net rate of household formation over the last 20 years.

- Of course, this is a chicken and egg issue – high prices could persuade children to stay with their parents for longer.

Affordability is a key issue, and though houses are more expensive than 35 years ago, they are probably more affordable, since mortgage rates are around six times lower.

- The biggest problems for most first-time buyers are (1) saving the deposit and (2) finding someone to lend them the rest of the money.

Paying the monthly interest is less of an issue, and often less than the equivalent rent.

In The Spectator, Tory MP Anthony Browne made a similar argument.

- His article has been criticised for misquoting a survey of economists, and he clearly has an agenda to avoid the paving over of his constituency.

But the central points remain:

- We can’t rapidly increase the number of houses in the UK, and

- Buyers will borrow as much as they can afford and drive prices up to that level in order to get the house of their dreams (or as close as possible).

Diversifiers

Adventurous investor David Stephenson ran through his idea of diversifiers.

Sensible investors will look to diversify. But in a globalised market where everything

seems correlated, including much of the bond market, that’s a tough nut to crack.

David split his ideas into two groups:

- things unrelated to the business cycle

- this includes the nuclear industry (uranium) and carbon emissions and crypto, plus some more conventional diversifiers

- diversifying equities

- this includes tobacco and healthcare

I have exposure to all of David’s diversifiers – though not necessarily through the same vehicles – with the exception of tobacco and Chinese debt.

Pensions

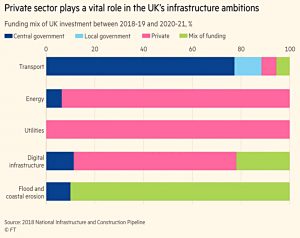

Josephine Cumbo had a couple of articles in the FT on the push to get pension schemes to invest in longer-term assets.

- The 5,000+ DC schemes in the UK hold more than £500 bn in assets

The Productive Finance Working Group (PFWG), run by the BoE, Treasury and Financial Conduct Authority urged the industry to shift its focus from low costs in order to invest in the UK’s post-Covid recovery.

- This means PE and VC, which are too expensive for the current pension fee cap of 0.75% pa.

The PFWG said:

Since the introduction of automatic enrolment, several million low and middle income workers have been placed into pension saving for the first time and, against a historic backdrop of high charges, the cap has encouraged competition around fees and resulted in lower charges for members.

However, there is an excessive focus on cost, rather than long-term value. We believe it is vital to develop suitable products that will enable schemes to access a wider range of investments, which may offer the opportunity to improve member outcomes in retirement.

Performance fees are the sticking point since DC schemes are typically much more open to equities in general than are DB schemes.

- Unlisted equity might not be to everyone’s taste, but if it could be accessed at similar fee levels to listed equity, you might expect at least some schemes to be interested.

Instead, an FT survey of 22 DC schemes and asset managers found that there was widespread reluctance to invest in illiquid assets.

- This stems in part from the recent gating of property unit trusts when underlying asset prices fell, though that particular issue is easily solved by using listed vehicles like ETFs and investment trusts instead.

There were also worries that a focus on UK investments was in conflict with fiduciary responsibilities to invest globally.

Petrol

As you no doubt have noticed, there have been long queues at UK petrol stations, and most have run out of fuel at some point in the last few weeks.

- The problem is partly one of supply (not enough tanker drivers rather than too little fuel overall) but more so of demand (panic-buying, triggered by media speculation about potential shortages).

Petrol, like many other supply chains, works on a just-in-time basis and has no way of coping with a five-fold increase in demand.

- We (the public) have obviously learned nothing from the great toilet roll and pasta shortages in the early days of Covid.

In The Critic, Christopher Snowdon argued that the crisis could have been avoided if petrol stations had simply raised the price of fuel.

- This kind of thinking plays very badly in the middle of a panic, but it makes economic sense.

When goods are priced too low, it makes sense to stockpile (or in the case of petrol, panic-buy to ensure your tank and jerry cans are full).

- The usual argument against “price gouging” is that it works against the poor, but it’s not clear how empty stations result in them getting hold of more petrol.

And the time/productivity spent queuing will never be recovered.

With prices high, only those who really need to get to work would pay for fuel.

- And the increase in profits would incentivise retailers to bring more goods to market while they can sell them for a lot of money.

Christopher draws an analogy with rent controls:

Though popular with the public [they] are almost universally condemned by economists who know from bitter experience that capping the price of rents does not lead to an abundance of affordable housing. Instead, it leads to a shortage of housing and a decline in the quality of the housing stock.

We seem to be developing a moral outrage in the country about people with more money having access to more and/or better goods and services.

- In which case, what is money for?

The alternative to high prices most commonly advanced in the present crisis has been rationing.

- Which is a little too close to communism for me.

Quick Links

I have six for you this week; the first five are from The Economist and the first four are about the energy revolution:

- The Economist said that the age of fossil-fuel abundance is dead

- And that hydrogen’s moment is here at last

- But that creating the new hydrogen economy is a massive undertaking.

- The newspaper also said that Volvo’s IPO will keep it ahead in the electric car race

- And that Facebook is nearing a reputational point of no return.

- Musings on Markets looked at the IPO of Indian fintech Paytm.

Until next time.