Weekly Roundup, 28th April 2015

We begin today’s weekly roundup as usual in the FT, with Merryn’s column.

Contents

China is the new Japan

Merryn imagined going back to the Japan of the 1950s – long before the Japanese stock market bubble of the 1980s had started. She pointed out how the fantastic growth of the 1950s and 1960s – an average growth rate of 9% over the period – didn’t lead to an increase in the stock market.

Instead, in the 1970s, when growth had fallen to 4% pa, the market multiplied by four. In the 1980s it multiplied by ten. There were three factors involved:

- companies make bigger profits once expansion and investment have completed

- international investors entered the Japanese market

- the Bank of Japan started printing money to force down the yen when the US suspended the gold standard

Merryn wondered whether China could be the new Japan:

- growth is collapsing

- the stock market has doubled in a year

- foreign investors are still hugely underweight

- the stock market is being liberalised

- the Chinese are in favour of printing money

Other parallels include the dodgy economy and the poor corporate governance.

If the analogy holds good, there could be another 800% to come from China over the next decade.

Inequality

Tim Harford’s Undercover Economist column dealt with myths about inequality, starting with the myth that Piketty’s book Capital showed that wealth inequality is at an all time high.

- In fact he only demonstrated that wealth inequality has risen since the 1970s, after falling for the earlier part of the twentieth century. We are still well short of the inequality of earlier centuries.

- A second myth is that the share of wealth owned by the top 1% is increasing. They do own a shocking 48.2% of all wealth as at 2014, but this is lower than in 2000. Global inequality is also falling, as wages in countries like China and India rise. But inequality within many countries is rising.

- A third myth is that inequality has risen in the UK since the financial crisis. The latest data from April 2013 shows it has fallen. ((Though it’s possible that it has risen since then))

Tim went on to discuss a new book by Professor Anthony Atkinson called Inequality: What can be done? The book offers proposals to deal with rising income inequality in countries like the UK and the US over the past 40 years.

The main idea is redistribution. This already happens to a significant degree in the UK: the top 20% have 15 times the pre-tax income of the bottom 20%, but only 4 times the post-tax income. Atkinson would like to see a lot more:

- 45% income tax from £65K pa, and 65% tax above £200K

- a “state inheritance” paid to every 18 year old

- guaranteed public employment

- increased inheritance tax

- more property taxes

This is quite the list – not even Ed Milliband and the SNP plan to go quite that far. It’s pretty easy to imagine that such taxes would be counter-productive and might cripple the UK economy. But that doesn’t stop academics dreaming up proposals like these.

Active vs passive

The Economist looked at the active versus passive investment debate, and in particular at a new paper that casts doubt on the recently fashionable idea of active share.

It had long been known that active fund managers as a group underperform the market but in 2009 a paper called How Active is Your Fund Manager? suggested that only closet trackers of the index were doomed to fail because of management costs. Those with a more independent approach (a high active share) might outperform. A second paper in 2013 called Active Share and Mutual Fund Performance backed this idea.

But now a third paper – Deactivating active share – has found that the active managers who did will were simply following a different benchmark, usually one for smaller companies. When compared to 17 American indices, high active share funds beat 8 of them but underperformed nine.

That high active share funds don’t in aggregate outperform is not surprising – it just as likely that the move away from an index will be in the wrong direction as the right one. The trick is to choose the right managers of high active share funds.

But what remains true is that paying high fees for closet tracking is a bad idea, and easily avoided.

The newspaper also reported on the decision by US financial regulators to hold a British day trader from Hounslow responsible for the 10% flash crash in US equities back in May 2010. Nav Sarao is accused of spoofing – submitting orders that he had no intention of completing. The authorities claim he used a computer programme to tweak the prices so that the orders were never taken up.

The result of entering lots of orders that would be profitable only if the futures market fell was to make market sentiment more negative. When the price fell, Sarao would buy, then cancel the depressing orders and wait for the price to rise again.

He continued to use the technique after the flash crash, but without a repeat of the mini-crisis. It is unlikely in any case that he was the sole cause of the crash, although he was responsible for $2ooM of sell orders, more than 20% of the daily volume in the contract he traded.

Junk bonds

Buttonwood looked at the erosion of the old division between boring and safe government bonds and racy, high yielding “junk” corporate bonds. With Greece possibly about to default and several countries selling bonds with negative yields, things have moved on.

The junk bonds have been surprisingly resilient, also. Since 1983 their default rate has been 4.9%. But before 2002 it was 6.9% and since then only 1.5%. The only recent bad year was 2009, at 15%. This is despite a gradual deterioration in the ratings issued by credit agencies, with more bonds falling into the lowest “C” groups.

The Economist cites the virtuous / vicious cycles in corporate bonds which arise because issuing companies also borrow from banks. When banks lose faith, they withdraw their loans and companies often default on their bonds. When confidence is high (as recently) junk bond issuers pay less interest on their bank loans, and find it easier to service their debts, driving their rates down further.

Monetary policy has also driven interest rates to zero, making the extra yield of junk bonds more attractive, and allowing issuing companies to lock in lower rates for longer periods.

Deutsche Bank has found that defaults lag the emergence of a flat yield curve (long-term rates as low as short-term rates) by two and a half years. Under such circumstances, banks have less incentive to lend and companies run into problems. High real rates also have the same effect, with the same 30-month lag. They predict a new wave of US defaults in 2H17. Europe has a shorter lag, and trouble may arise in 2H16.

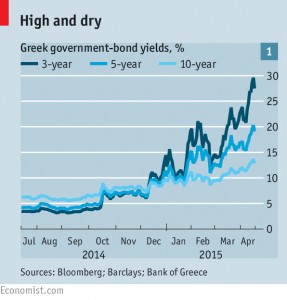

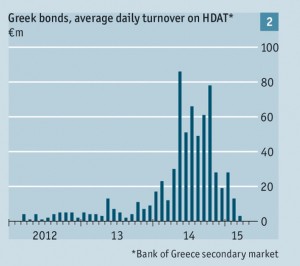

Grexit

Finally, the Economist looked at Greece, and the reluctance of traders to make bets on the likely outcome of the current crisis. Back in 2012, Greek bonds doubled, and 2013 stocks rose by 40%, so their reluctance is a little surprising.

Greek 3-year bonds now yield 27%, and the 10-yr bonds are at their highest yields since 2012. S&P has downgraded the bonds to junk status and credit default swaps predict an 80% chance of default within five years. Things have become too risky for foreign investors – only 11% of Greek government bonds are held privately.

On the stock market, firms trade at an average of 60% of book value. Bookmakers offer odds of Greece adopting a new currency in the next 3 years of 5/4, of 3/1 on an election in 2015 and 2/1 on Greece leaving the euro this year.

The newspaper also looked at the possibility of the Greek government issuing IOUs. Greek debt is €315bn or 175% of GDP and €2.4bn is owed before the end of June. To save cash, the government could issue “scrip” which would be redeemable against taxes in the future. As most of the state’s outgoings are paid to Greek citizens – €22bn in salaries and €35bn in benefits, from a total pf €80bn – this would be significant.

Scrip has been used in the US, most recently in California in 2009. Those warrants carried 3.75% interest and could be exchanged for dollars at local banks (who then pocketed the interest). Of course, California’s economy is eight times the size of Greece’s.

A better comparison might be Argentina, which in 2001 issued lecop to the tune of 50% of the amount of pesos in circulation. Complications arose when cities issued their own scrip, and there ended up being a dozen non-fungible types. Hoarding of pesos also became a problem. This is a case of Grehsam’s law – bad money chases out the good. ((The law originally applied to coins with varying levels of precious metal content, but seems to apply just as well to paper money.)) Barter also became common, which impacted tax collection.

So the issue of scrip would just transfer the state’s euro shortage to the banks, and could well reduce the tax take. But it would only buy a few months breathing space. In the end the government must earn and collect more euros, and spend fewer.

Until next time.

2 Responses

[…] Next Merryn discussed the scary demographics of Europe, and how they doom the continent (including the UK) to weak growth in the years ahead. The final part of her talk was a re-hash of her Weekend FT column describing the similarities between present-day China and Japan just before the 1980s boom (which we covered in yesterday’s Weekly Roundup). […]

[…] looked last week at radical left-wing proposals to address inequality, this week Tim Harford put forward a hypothetical radical conservative agenda. His first […]