Weekly Roundup, 12th December 2022

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup with pensions.

Can you retire?

The Economist warned that inflation and rising interest rates could mean that retirees would have less money than they previously thought. (( As if we hadn’t worked that out already ))

Higher interest rates have caused a repricing of bonds and stocks. The result is that the pot of assets many future pensioners are hoping to live off has shrunk.

And that’s before we consider the demographic pressures (more retirees, fewer workers).

The newspaper highlights in particular the predicament of near-retirees who have been “life-cycled” out of stocks and into bonds just before their works year ever.

- The typical portfolio of those about to retire is down 17% during 2022 (before factoring in double-digit inflation).

Some people have lost 25% of their real purchasing power in ten months.

A year ago, a 65-year-old who had saved a healthy $2.5m for their retirement and invested 80% of it in government bonds and 20% in equities, would have typically drawn an income of $100,000.

Now the pot is worth $2.1M and they can draw only $83K, which is worth $75K after 10% inflation.

-

- If inflation remains above 2% pa for some years, then this pensioner might have even less as they get older.

The other side of the coin is the DB pension system, which contains $17 trn of the $40 trn in US retirement assets.

- DB schemes have been on the way out since the late 1980s, as employers worked out they were too expensive to run in a low-interest-rate world.

But the public sector (ie. the taxpayer) is still stuck with a lot of DB schemes.

Around $13trn of America’s defined-benefit assets are managed by state, local and federal governments.

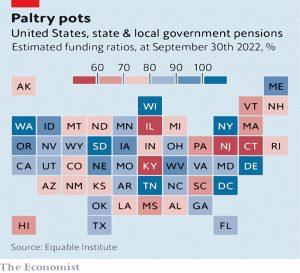

And as the boomers hit retirement age, these pots are not in great shape, as measured by their funding ratio (the pot value vs. the present cost of future obligations).

The sum has three moving parts: the value of the current investment pot, the discount rate used to calculate the present value of future payouts, and the stream of those expected future payments.

The stream of future payments is never entirely clear, but the other two numbers count for more.

- Matching the pot to future spend is called liability matching, and is usually achieved by buying long-term bonds to pay out in the future (regardless of falls in their capital value). ((The derivative-based version of this is LDI, which caused UK pension schemes some problems when yields rose in the summer ))

But if the pot is in deficit when this strategy is implemented, the deficit is effectively locked in.

Many underfunded pensions have had to take risks—by holding equities, for example—in a bid to fill their funding gaps. A combination of bad investment years (such as 2001 or 2008), falling discount rates, ageing populations and the political infeasibility of asking employees to contribute more has pushed a lot of DB schemes into the red.

Higher rates look like they make things worse (since long-term bonds fall in value).

- But the higher discount rate reduces the present value of future payouts, so the funding rate can improve.

After a bumper 2021, the average corporate pot was fully funded at the end of the year, for the first time since 2007. Corporate funds then moved to reduce their investment risk early by swapping many stocks for bonds.

Public sector pensions haven’t done so well.

The average funding ratio for public pensions in America, which stood at 86% a year ago, their highest since 2008, has dropped to 69%—close to a five-year low.

One problem is that discount rates are set by a committee rather than the market.

These committees did not reduce discount rates by as much as interest rates fell over the decade that followed the financial crisis, which made it difficult to raise them by very much this year, as interest rates rose again.

So the value of liabilities remains high, whilst investments have performed poorly this year.

At around 40% funding, a pension scheme is unable to pay out its annual liabilities from income and has to start selling assets instead.

- Eventually, there are no assets left, and contributions from current workers must match payouts to former ones (“pay as you go” – already used in UK and US state pensions/Social Security).

It is becoming a scary possibility in American states like Kentucky, Illinois, Connecticut and New Jersey, where public-pension plans are now around just half-funded.

Many states could end up looking for a central government bailout.

VCTs

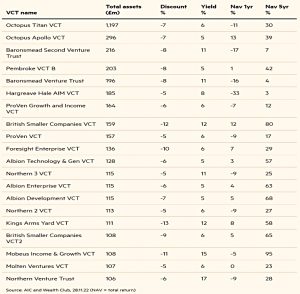

For the FT, Mary McDougall tried to work out whether VCTs were overpriced, or if it was time to buy.

- There are around 80 VCTs with investments in more than 1,000 underlying companies, managing £6.1 bn of funds.

Regular readers of this blog will know that I buy around eight VCTs each year, and I have a portfolio of forty funds in various sizes.

- There’s more on my own adventures with these vehicles here.

Enthusiasm for VCTs is largely thanks to the tax perks. VCT investors can claim income tax relief of 30 per cent up front, providing they hold the shares for at least five years. Most VCTs target dividend payments of around 5 per cent and these are shielded from dividend tax too.

With pensions limits shrinking and now the cuts to the dividend allowance, these perks are increasingly attractive.

- And some (albeit biased) commentators think that now is a good time to buy.

Malcolm Ferguson, manager of Octopus Titan VCT, said:

The first two years of a recessionary cycle are often some of the best to invest in a business.

He gives three reasons:

- access to better talent as larger firms lay off staff

- funding scarcity reduces the likelihood of a rival popping up

- incumbent companies are less likely to develop a competing product

The table lists twenty large funds with open offers during this tax year.

The weighted average NAV return for all VCTs over the last 10 years is 101%

- But two-thirds of those with five-year track records have returned less than 30%

Like all venture investing, there is a long tail of poor performers.

- And ongoing fees charged by managers are high.

This year, generalist VCTs are down 4% and AIM VCTs are down 29%.

My own portfolio is 5.7 years old, or 4.2 years old on a money-weighted basis.

- After accounting for the up-front tax relief, it has been compounding at 15% pa so far.

Private Equity

Sticking with unlisted equity, in The Economist, Buttonwood explained how private equity (PE) seems to have avoided the asset-price crash.

A huge gap between the valuations of publicly listed companies and their unlisted peers’ has opened in 2022. The enterprise value of firms held by private-equity funds globally rose 3.2% for the year to date. The S&P 500, by contrast, fell 22.3% in the same period.

This lower volatility helps institutional investors, like pension funds, who would rather not report large losses.

- But private firms which are smaller and often more leveraged should probably do worse when inflation and interest rates rise.

The most obvious explanation is that shares in private firms are traded infrequently – they are not “marked to market”.

- And only a quarter of PE firms use independent external valuers to check their growth estimates and discount rates.

In the 2007 crash, US buy-out funds were so slow to mark down their holdings that the 2009 recovery meant that some of them never had to.

Cliff Asness of AQR once dubbed such obfuscation tactics “volatility laundering”.

He has been vocal on Twitter on this topic in recent months.

Gilts

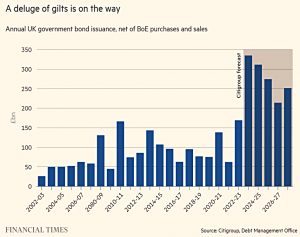

In the FT, Tommy Stubbington wondered who would buy an “historic deluge” of UK debt.

The Debt Management Office will need to sell an average of nearly £240bn of gilts for each of the next five financial years. That figure comfortably eclipses previous records, with the exception of the vast borrowing during the coronavirus pandemic.

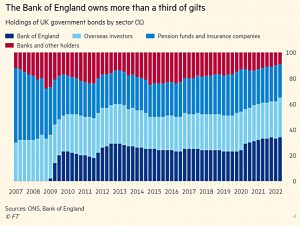

In 2020, the Bank of England (BoE) bought most of those gilts through QE, but now the BoE is unwinding its £800 bn of QE bonds.

- So the net issuance will be the highest ever.

The UK will be joined in its record issuance by the eurozone, in response to the energy crisis.

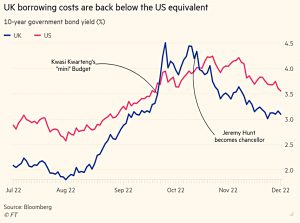

- But the supply of bonds is not a major driver of yields, as can be seen from the calm in the market.

The BoE is the biggest owner of gilts, with the rest split fairly evenly between other domestic investors (banks, pension funds and insurance companies) and foreign investors.

In recent years, UK issuance has focused on liability-driven investors (LDI):

Pension strategies that use long-term assets to match their long-term commitments to pensioners and were at the centre of the autumn’s gilt market chaos. However, the longer-term decline of the defined benefit sector — such schemes are mostly closed to new members — means this source of demand will wane.

This issuance has meant that gilts have a longer maturity than other government bonds.

More than 14 years, compared with six to eight years in other G7 economies.

With domestic demand declining, how likely is it that overseas investors can step up to match the likely doubling of supply?

- One likely outcome is higher borrowing costs (higher yields than on US Treasuries).

It’s also possible that disinflation (or deflation) or a recession will increase demand for bonds.

Quick Links

I have five for you this week:

- Alpha Architect looked at The “Resurrected” Size Effect and Monetary Policy

- And at Investing in Deflation, Inflation, and Stagflation Regimes

- The Economist wrote about The rise of the super-app

- Mauldin Economic provided a Recession Scale

- And 3Fourteen Research looked at the Path to a Pivot.

Until next time.