Weekly Roundup, 12th January 2016

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup in the FT, with the Chart that tells a Story.

Contents

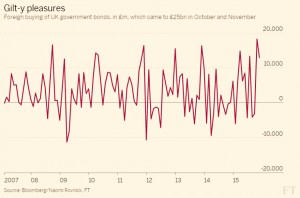

Foreign buyers of Gilts

Or rather, as is usually the case these days, four charts. ((The FT seems to have stuck with the old one chart format in the printed paper, but with a bigger article behind it on the website ))

Naomi Rovnick took a look at sales of UK government bonds to foreign investors.

In October and November 2015, they bought £25bn of gilts, the most for 25 years.

- The long-term average is £4bn per month.

UK bonds are cheaper than those of Spain and Italy, whose economies are weaker:

- yields on Spanish and Italian 10-year bonds are 1.6% and 1.5%, compared with 1.9% for the UK

- this is mostly because the ECB has been buying up euro zone debt, though its possible that fear of Brexit is starting to be a factor

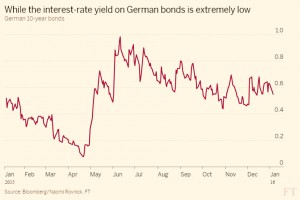

German bonds are even more expensive:

- the 10-yr bund yields 0.6%

Naomi also points to a general move from riskier stocks to bonds because of the recent volatility in the Chinese stock market.

The bull market in Gilts could be halted by a rise in UK interest rates, though most observers think that is not going to happen in the short-term.

Contrarian indicators

Naomi also reported on retail investors pulling money out of global equity funds.

- It’s a somewhat sensationalist headline, as withdrawals have only reached a five-month high, but it’s worth considering.

- Bond funds had net inflows of $3.2bn, compared to equity outflows of $8.8bn.

Although equity markets look shaky at the moment, my general practice is to take things like this as contrarian indicators.

- Retail investors are notoriously poor at market timing, and often when they are getting out of somewhere, it’s actually time to get in.

A couple of other articles in the mainstream media (MSM) backed up this impression. First, the BBC website has been leading off and on with the falls in the Chinese market.

- This is definitely overstated. The Shanghai exchange is dominated by retail investors and has less to do with the Chinese economy than even the FTSE-100 has to do with the UK economy.

- It’s a gambling index, regulated by novices in market intervention. The circuit breaker idea has been abandoned after only four days.

- That’s not to say that a Chinese slowdown isn’t happening, and won’t have impacts across the globe (see below), but rather that MSM focus on a relatively trivial issue is another good counter-indicator.

Second, the Telegraph reported this morning that RBS have been advising clients to “sell everything” (apart from high quality bonds).

- They are worried that Chinese devaluations and falling demand could drive commodities even lower, impact international trade and lead to global deflation.

- This is a plausible if not very likely scenario, but more significant is the sensationalist wording (“sell everything”) and the fact that it has been picked up by the MSM.

Taken together, these three pieces of evidence make it feel like we might have just seen the bottom for now.

Contrarian timing

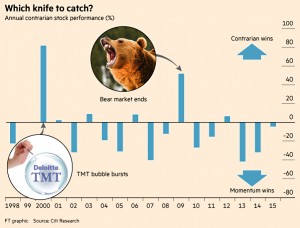

With good timing himself, Dan McCrum looked at the art of timing contrarian trades. To be a truly celebrated investor, you need to go against the crowd at some point.

At this time of year, many people come up with the idea of selling what went up last year and buying what went down.

- Which this year means commodities and energy companies, and the oil price itself.

The trouble is, the opposite of buying what went down – buying what’s recently gone up – can also work well.

- This is one of the basic tensions in investing – contrarian versus momentum investing, or mean reversion versus trend following.

So when is the best time to buy? Dan looked at a study by Citi comparing strategies of selling the best ten stocks and buying the ten worst (contrarian) with the opposite (momentum).

- In general, momentum wins.

- It’s harder (and less profitable) to try to pick turning points than to stick with winners.

But this may be a product of the calendar year timing and reviews. Many contrarians would argue that:

- you need to wait for the trend to reverse, rather than buying on 1st Jan

- contrarian outperformance will show up in 2 or 3 years, rather than one

Personally, I’m a big fan of momentum and trend-following, but now and again valuations become so extreme that the contrarian trade becomes attractive.

- I hope at some point this year that commodities and energy stocks will become attractive propositions

- Gold and silver miners look promising as well

But since I will wait for the trend to turn before I buy, am I really aiming to be contrarian?

- Or am I just jumping aboard a new trend that might have a long way to run?

It’s all a matter of timing.

Dogs that didn’t bark

Although most commentators are pointing to China as the cause of market weakness, John Authers wanted to look a number of “dogs that didn’t bark“.

First up was a strong US jobs report that produced a lukewarm response from the markets.

- The Fed repeated its intention to raise rates faster that the market believes is possible.

- The jobs report gives this plan some credibility, but still falling commodity prices do the opposite.

Second was the Eurozone ISM supply manager survey showing increasing confidence.

- With a weak euro and central bank stimulus, the Euro zone markets should be doing well, but they are not.

John also noted that the spat between Saudi Arabia and Iran failed to push up oil prices.

And in the US, there is increasing disbelief in analysts forecasts of increasing corporate earnings during 2016.

- With PE valuations already high, US stocks are set for a fall.

The good news is that stability from China or positive earnings surprises could lead to gains on either side of the Atlantic.

- But the opposite is also the case.

2008 all over again

In the Economist, Buttonwood wondered whether 2016 would be 2008 all over again. Both George Soros and George Osborne have recently warned that it might be.

- But the World Bank is predicting 2.9% global growth, which would be better than 2015.

Since forecasters rarely predict recessions, perhaps the trend in forecasts is more instructive.

- In Jan 2008, the Fed predicted 1.3% to 2% growth, down from 1.7% to 2.5%.

Falling commodity prices and bond yields here in Jan 2016 indicate that investors are worried about growth once more.

The US manufacturing ISM indicator is at 48.2. China’s PMI is at the same level.

- A fall below 45 would be a reliable signal of a downturn.

Global trade is also slow, but the US service sector ISM is at 55.3, and the jobs report was strong (see above). German manufacturing is also doing well.

Perhaps a catalyst is needed to trigger global recession.

- Iran and Saudi Arabia have fallen out, but a real war between them might do it.

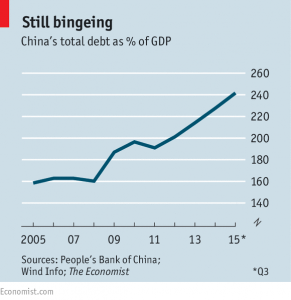

To match 2008, the trigger would need to be a debt bubble bursting.

- Soros suggested China, where there has been a 50% increase in the debt-to-GDP ratio over the last four years.

- This suggests that credit quality is not being properly checked.

But state controlled China should be able to handle a debt crisis, and contagion to Western banks should be minimal.

- Zombie companies might hang around and depress corporate earnings, though.

A Chinese devaluation is a bigger threat.

- Apart from being deflationary, other Asian countries would follow suit, and their companies with dollar debts would struggle.

- Banking problems might spread across Asia.

So there are real risks, but they are more an echo of 1998 than 2008.

- And since emerging markets are much more important now, it would be worse than 1998.

GDP forecasts

The only function of economic forecasting is to make astrology look respectable. – John Kenneth Galbraith

As 2016 forecasts for economic output are published, the Economist looked at whether forecasters ever get it right.

There are two approaches to forecasting:

- theory, using models that predict how economies should behave, and

- data, looking at how they have behaved in the past

- The simplest theory is the Solow growth model, which says that poor countries should invest more and grow faster than rich ones.

- Central banks use more complicated “dynamic stochastic general equilibrium” (DSGE) models. These look at the behaviour of individual households and firms, but are still oversimplifications.

- Data models look at the relationships between thousands of variables, from vegetable prices to the weather. But it is difficult to isolate cause and effect.

- Some forecasters – the IMF for example – combine the two approaches with a dash of common sense.

But none of the forecasts are very accurate.

- They seem to suffer from cognitive bias, assuming the future will be like the recent past.

Regression to the mean is a more reliable long-term factor:

- fast-growing countries slow down, and vice versa

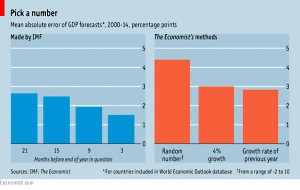

The Economist looked at 15 years of IMF forecasts, comparing them to three unsophisticated predictions:

- that a country will grow at the same pace as the year before

- 4% growth (the average growth across all countries during the period)

- a random number between 2% and 10%

- The random guess came last, off by 4.4% on average.

- Previous year’s rate was next worst.

The best prediction was the one made by the IMF in October of the year in question, when 9 months of data was already known.

- But even here the average error was 1.5%.

- The earlier the IMF forecast, the less accurate.

The Economist also noted how bad the IMF was at predicting downturns.

- There were 220 instances of growth followed by shrinkage the next year.

- The IMF predicted none of these in its April forecasts, and only half of them in October.

So don’t worry too much about GDP forecasts. They are usually off by 2%.

Until next time.