Weekly Roundup, 17th October 2017

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup in the FT, with Merryn Somerset Webb. This week her column was about the pulled launch of the People’s Trust.

Contents

People’s trust

Merryn reported that Daniel Godfrey had pulled the launch of his People’s Trust.

It was to be a mutually owned trust with returns judged over a full seven-year rolling time-frame and assets managed by a group of fund managers chosen for their long-term stock-picking skills.

Unfortunately it was also going to pay Godfrey a handsome salary and charge more than 1% pa at startup.

- This was somewhat ironic since he was forced out from his previous job as head of the Investment Association for suggesting that fund manager should be paid less and funds should charge less.

The fund needed to raise at least £50M to be viable, and has only managed to raise around £25-£30M.

- Merryn puts the failure down to the high initial charges and the similarity to established funds like Alliance Trust and Witan.

- She also mentions Caldeonia, RIT Capital Partners, Troy Trojan and Baillie Gifford Managed as alternatives.

She also points out that “one-stop shop” funds like this are a hard sell for investment managers (what is their value add if the investor could do the same thing on a DIY basis?).

- And she worries that Hargreaves Lansdown now have such a stranglehold on DIY investors that you can’t have a successful fund launch without their full-hearted backing.

I do hope not, but only this week, FT Advisor reported that HL was increasing its assets under management while its rivals struggled.

- Assets were up 4% to £82 bn in the three months to the end of September, but £1.3 bn of the £2.8 bn increase was down to market rises.

HL also increased its client base by 30K during the period, taking it to 983K active clients.

- Many of the transfers came from Barclays, which has introduced an unpopular new system.

Of the £82 bn in assets, £46.6 bn are in funds, £27.1 bn are in shares and £8.8 bn are in HL’s own funds.

- I’m going to guess that ETFs and Investment Trusts are bundled in with shares, which shows a shocking bias to more expensive funds.

Merryn also mentioned inheritance tax as a potential solution to the housing crisis.

- She would like to cancel IHT on all assets except residential housing.

This would encourage the elderly to sell their homes and downsize or rent for a few years before they die, freeing up cash to pay for their social care.

- It might work, but it would need a revolutionary like Thatcher to introduce it.

Popular capitalism

In the Economist, Bagehot looked at the policies of three groups within the Tory party.

First, he demolished two of the groups:

- The Thatcherites, who want post-Brexit global tariff-free trade and see capitalism as the solution rather than the problem, (( I am one of them, of course ))

- their problem is that there are enough cheap council houses to sell-off in order to solve the housing crisis

- and the One-Nation Tories, who accept the role of the state in such problems

- their difficulty is avoiding coming across as Corbyn-lite, and acting as a gateway drug to communism.

He also points out that Theresa May seems to swing between these two extremes.

Bagehot prefers a group of younger Tories (without a name) who accept the problems of social exclusion and low productivity, but don’t see a 1970s-style Big State as the solution.

Their “new” ideas include:

- a mandatory shareholders’ vote on bosses pay (a good idea)

- encouraging workers to own shares in the company they work for (a bad idea – they need shares in other companies instead)

- allowing family firms to go public without ceding control (a good idea, in principle)

Bagehot would also like to see more encouragement and support for internet-driven startups in fintech and AI, both of which the UK seems to be good at.

- So would I.

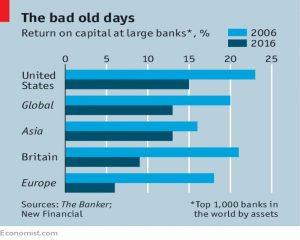

Banks are still risky

Buttonwood looked at the finance industry ten years after the crisis, and came to the conclusion that banks are still risky.

- They carry more capital on their balance sheets now, which means that their return on capital has fallen by a third between 2006 and 2016.

- And Chinese banks have risen in importance.

Investment banking revenues are down 34%, and profits 46%.

- ROE is down by two-thirds, and pay by 52%.

Trading and equities are now less important relative to corporate finance and debt.

- That’s because despite records highs in the US, stocks in Europe and Asia are smaller as a proportion of GDP.

Despite this, trading volumes in stocks, FX and derivatives are up.

Asset manager profits are up 30%.

- And the industry is more concentrated.

Despite the extra capital, we still have high asset prices and lots of debt.

Which means that the banks will be at the centre of it all once again.

IMF on tax

Buttonwood also notes a rare agreement between the Guardian and the Daily Mail:

- They each believe that a recent report from the IMF provides support for Corbyn’s policies on tax.

The report suggests that rich countries could reduce inequality without impacting growth by increasing the top-rate of tax.

As an average, that is true, but unfortunately the devil is in the detail:

- the optimal rate for the top rate of tax is 44%,

- and while the OECD average for the top rate is 35%, the UK already has a top rate of 45%.

So in fact the IMF are recommending that the UK reduce income tax.

And they are saying that Corbyn’s policies will lead to:

- more incorporation to avoid higher income tax, and

- companies moving away from post-Brexit Britain to avoid higher corporation tax.

Thaler’s Nobel

The Economist also covered Richard Thaler’s Nobel prize win, which we covered briefly last week.

- Thaler was responsible for the insight that normal humans don’t behave in the same way as homo economicus – the “rational man” of most economic theory. (( It’s important to note that this is not a good thing – homo economicus does the right thing, and I strain to emulate him ))

Other notable contributions to the field have come from Herb Simon, Daniel Kahneman and Robert Schiller, all of whom also won the prize.

- Notable non-winners who have added to behavioural economics and its application to finance include Dan Ariely and James Montier.

Thaler is best known for “nudges”, once adopted by David Cameron’s government in the UK.

- This work was based on the asymmetry of losses (they hurt more than equal gains) and the endowment effect (we value things we own more than a non-owner would).

He also uncovered “mental accounting” where people group some kinds of money and spending together, yet keep other kinds separate.

- And like Kahneman, he saw choices as battles between two cognitive systems – in his terminology, “the planner” and “the doer”.

Nudging involves framing choices in such a way as to favour the planner (opt-out auto-enrolment to workplace pensions, for example).

Tim Harford’s column in the FT was also about Thaler.

- He focused on Thaler’s achievement in persuading economists that people don’t behave like Mr Spock from Star Trek. (( You might recall that James Montier uses the same analogy ))

Tim is interested in how he did this because:

The world is full of stubborn-minded people who need to be persuaded to change their views about important things.

I imagine he has in mind people like me, and things like Brexit.

Tim has identified four techniques used by Thaler:

- Persistence – he started way back in 1980.

- Honest engagement with – and understanding of – his opponents’ positions.

- Sticking to the facts of everyday human behaviour, rather than statistics.

- Curiosity – he liked to find puzzles, and try to solve them.

Taxing fat

The Economist also reported that taxing fat (and / or sugar) – and subsidising healthy eating – widens inequality.

- The poor spend a higher proportion of their income on food and also eat less healthily, so are hit harder by the taxes.

This is true, but it’s also kind of the point.

- If we want to favour good behaviour over bad behaviour (and we could define good here on moral grounds, or via externalities such as extra costs to the health service) then by definition those exhibiting the bad behaviour will suffer.

A similar argument is made when subsidies are reduced (eg. welfare allowances) – that the areas which can least cope with the reductions are hit the hardest.

- Well or course they are – they were the areas that benefited most from the higher subsidies in the first place.

A policy is either right or wrong – it will never fall evenly on all people.

The article takes the discussion further, describing an experiment in France which used both taxes on bad food and subsidies on good food.

- As expected, taxes hit the poor hardest, since they didn’t change their habits.

- Subsidies encouraged all groups to buy more fruit and veg, but the rich increased their consumption by more.

The explanation is simple – some people think long-term, and others think short-term.

- And those who think short-term are more likely to be poor.

This division is not just found in food, but with other areas of life where good and bad choices are well understood – exercise, substance abuse, tattoos and – most relevantly for this blog – saving for retirement.

Safe Withdrawal Rate

In the Telegraph, Sam Brodbeck looked at the latest estimates for a safe withdrawal rate (SWR) from a UK pension pot.

- “Safe” was originally defined as “providing a 95% chance of lasting 30 years”, but I’m looking for a bit longer (and a bit more certain) than that.

- Historically, a 4% pa rate has been used, though that applied to the US some decades ago.

- I’ve always preferred something much closer to 3% pa for the UK.

The latest estimate comes from Morningstar, who assume a 40% equity allocation.

- Their SWR for 2017 is between 2.2% and 1.9% pa, down from 2.5% pa last year.

- High valuations have pushed down expected future returns.

I tend to look at the problem in reverse, with the aim being to avoid selling equities when markets are low.

- I remain comfortable that a 3% pa withdrawal rate, coupled with a 5-year cash buffer will do fine.

Morningstar also looked at the impact of fees on a 3% pa withdrawal rate

- With a 0.5% pa fee, there was a 78% chance that the portfolio would last for 30 years.

- At the 1% fee level, the chance falls to 68%, and with 2% pa fees, it is just 46%.

Morningstar said:

Fee minimisation could be the single most important variable to increase the safe withdrawal rate for retirees.

Retirement income targets

Pensions Expert reported that the Pensions and Lifetime Savings Association (PLSA) has proposed the introduction of Australian-style national retirement income targets.

- We have a de facto target already, which is 70% of pre-retirement income.

- The shortfall from this target is used to calculate a national “pensions gap”.

Australia uses pot size targets instead, of £323K for a single person, and £377K for a couple.

- The PLSA haven’t defined their pot sizes, but their income targets are £15K pa for a modest lifestyle and £25K pa for a comfortable lifestyle.

- These seem reasonable, but I hope that they will lead to larger pot size targets than are used in Australia.

I will take a closer look at the paper, as I think it might deserve an article to itself.

Platforms for investment trusts

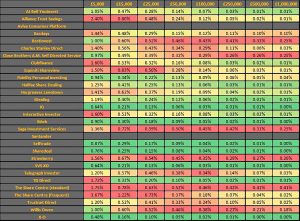

Money Observer looked at the cheapest and most expensive platforms on which to hold investment trusts.

- Since ETFs are usually lumped in with ITs on most platforms, I believe that these results could be extensible to ETFs.

The original research comes from the Lang Cat, via the AIC, and can be found here.

The table below shows the annual costs, as a percentage of your portfolio, from £5K to £1M.

- It assumes that you are a buy-and-hold investor and make only four trades a year.

Along with a few others, our perennial favourite iWeb comes out well at all portfolio sizes.

Twitter pics

I have six for you today.

The first shows the increasing divergence between the Fed’s balance sheet and US asset prices.

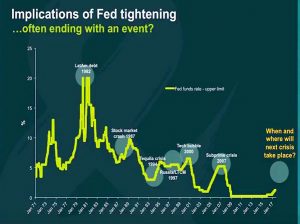

The second shows how Fed tightening usually leads to a crisis.

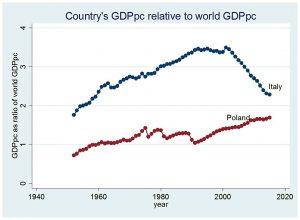

The third shows how close Poland is to catching Italy (in per capita GDP terms).

This one puts the current high level of house prices to earnings in the UK into its historical context:

- We haven’t hit the 2007 peak yet, and are only just above the one in 1950.

- The 1991 peak that many of us remember was substantially lower than today.

- And before 1910 (when not many people could afford to buy a house), the ratio was consistently above where it is now.

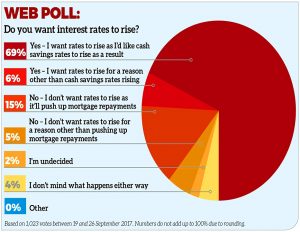

This one is more depressing:

- 69% of people in the UK want an interest rate rise so they can get more money on their cash.

- 15% don’t want a rise because their mortgage payments will go up.

The correct answers (raise rates to kill zombie companies and allocate capital correctly) took less than 6% of the vote.

- And were almost matched by 5% of people who didn’t want a rise for unspecified reasons.

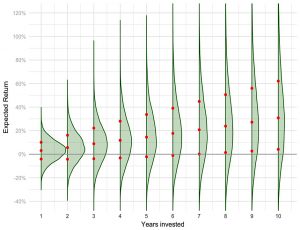

The final slide this week shows how the expected returns from stocks change as the holding period increases.

- The bulge just above zero is spread increasingly thinly, towards ever higher returns.

- But the portion “below the water” disappears more slowly.

- And the negative long tail at -40% never goes away.

Stocks are risky, so diversify with other assets.

Until next time.