Weekly Roundup, 18th January 2021

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup with a look at whether we are in a bubble.

Bubble

Quite a few people have been trying to figure out whether markets are currently in a bubble.

- Valuations are high in places (particularly the US, and stocks like Tesla) and there seems to be a lot of speculation around.

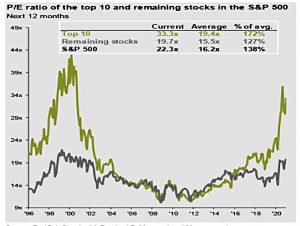

As Michael Batnick notes on The Irrelevant Investor, outside of the top 10 stocks, (which have a PE of 33) the other 490 stocks are at a 19.7 PE.

That said, the chart does make today look like a weaker version of the dot com boom.

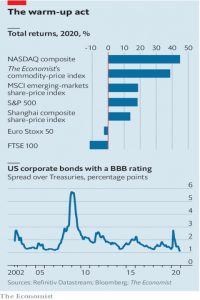

The Economist pointed out that stocks are still cheap relative to bonds.

Compared with the real yields offered on risk-free government bonds, equity prices have plenty of appeal. Equities do not have to beat their historical returns to be worth holding. They just need to outrun bonds by a decent margin.

The key idea here is that the inverse of the PE (known as the earnings yield) is a forecast of equity returns.

- This is essentially Shiller’s CAPE concept, which uses 10 years of yields.

It should be noted that high prices (low yields) don’t signify future bumper profits:

High house prices relative to rents signal low returns, not rising rents. Credit spreads on bonds are a signal of returns, not default probabilities.

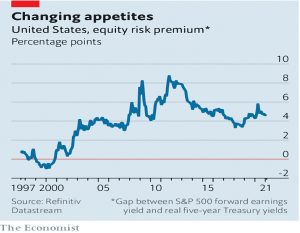

The article moves on to the risk premium:

The price of assets should equal expected cashflows discounted over the life of the asset. The earnings yield gives you the “expected” part of this equation; real bond yields cover the “discounted” part. The gap between these two is a forward-looking measure of the equity risk premium, the excess return for holding shares.

The premium has been higher in the past but is not particularly low at present.

During the dotcom boom, the premium for owning stocks was negative—real interest rates were a handsome 4%. Now real rates are negative.

As we noted recently, Shiller and his colleagues have concluded that equities are cheap relative to bonds, even in the US.

- But more so in the UK, Europe and Japan.

So absent higher interest-rates (which would probably require sustained inflation first), equities might be okay.

A second article looked at things that might get in the way of a melt-up, but concluded that none seemed “all that formidable”:

- Damage to the economy from Covid-19

- Excessive bullish sentiment

- Less stimulus than expected

- Inflation

- Too much debt

We’ll have more on this next week.

Bitcoin

The other popular topic of recent days has been bitcoin.

- The Economist looked at the latest boom and wondered whether the financial establishment was coming round to BTC.

Larry Fink of BlackRock, the world’s largest asset manager, said in December that bitcoin could become a “global market”. Big hedge funds such as Renaissance Technologies have been punting on cryptocurrencies. Ruchir Sharma, a strategist at Morgan Stanley’s investment arm, argues that America’s mounting debts may make cryptocurrencies more appealing.

Paul Tudor Jones has said one of his funds could increase its bitcoin position to as much as a “low single digit” percentage of its assets. Bill Miller as remarked that the chance of the token’s value falling to zero is “lower than it had ever been”. Stanley Druckenmiller has also warmed to the idea of using bitcoin as a hedge in place of gold.

On December 17th Coinbase filed to go public. A long-predicted bitcoin exchange-traded fund (ETF) may at last come to fruition in 2021.

And as we previously mentioned, Ruffer took a 2.5% position a couple of months ago.

The Economist remains unconvinced that bitcoin is fast (efficient) enough to be used as money.

- And if that problem were to be solved, regulation from governments whose monetary sovereignty was threatened would follow.

They are also unsure that it works as a store of value:

Its price is much more volatile [than gold’s] and moves with the stockmarket, which is hardly desirable for a supposed haven. The market is illiquid and cryptocurrency trading remains a wild west in which fraud and theft are rampant. Investors in cryptocurrencies must tolerate a large dose of financial and reputational risk.

In the FT, Merryn Somerset Webb also had some doubts:

My go-to inflation hedge will remain gold for the simple reason that it isn’t new.

I’m nervous about the next few years and I want a portfolio protector that has a

multi millennium record in the safe haven top spot.

She planned to buy other commodities too, but she wasn’t entirely negative on BTC:

I’ll be buying a little more [bitcoin] – not so much as to ruin me if it goes to zero, enough so that I don’t feel too awful at $500,000.

Meanwhile, IFA Neil Liversedge has started a petition to ban crypto transactions:

Prohibit the payment by or acceptance of cryptocurrencies by UK resident

businesses or individuals, and require UK regulators (the FCA and PRA) to prohibit

transactions by UK financial institutions in cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin.

He had three objections:

- The “destabilising effect” of speculation in an asset with no intrinsic value

- Its use for criminal activity, and

- The environmental harm caused by cryptocurrency mining.

I have a separate series of articles on the process of buying bitcoin in the UK – and the taxes you will pay on any profits – you can find these here.

SONG

In the FT, Jamie Powell reported on a note from Stifel questioning the strategy of the Hipgnosis Song Royalties fund (SONG – I hold).

The first issue is with the NAV.

- Alternative assets have no daily market to use for prices, so the cautious approach is to use acquisition cost until there is evidence that the value has increased.

SONG tends to increase asset value by 2% to 11% within 3 months of acquisition (using an independent valuation agent, Massarsky).

Max Haycock from Stifel says:

We use the following analogy. An individual purchases a house for £500k. That individual then goes to an estate agent and they receive an estimated valuation of £550k. The “gain” of £50k is then immediately booked by the purchaser who goes to their bank and asks for more capital to buy another house.

While the valuation agent is independent to the buyer they are also aligned to the success of the housing sector. Given Hipgnosis is a buy-and-hold investor and does not expect to sell catalogues, there will not be any confirmation of the DCF valuation.

The second issue is cash flow.

A song streamed today may not lead to a cash payment for at least six months

and possibly longer. This is highlighted in the interim accounts to 30/09/20 where total revenue was £50m versus ‘accrued income and receivables’ of £50m.

Performance Rights Organisations (PROs) can take up to two years to pay and make be responsible for 40% of accrued income.

Benchmarks

On Citywire, James Philips looked at how the pros did during 2020.

- Asset Risk Consultants (ARC) tracks the returns of 250K portfolios from 90 discretionary fund managers.

Returns for sterling investors ranged from 5.2% for its most high octane Equity Risk sector, for portfolios with 80-100% equity exposure, down to 4.4% for it Cautious index, where funds only invest up to 40% in equities. In the middle, the Balanced Asset index, with 40-60% equity exposure, returned 4.8% in 2020, while its Steady Growth index, holding 60-80% in equities, rose by 4.9%.

I target a 75% equity allocation (including equity alternatives like property), so my “benchmark” returned 4.9% (compared to my actual benchmark, which returned 3.5%).

- Which makes me feel okay about my actual 9.2% return.

ARC also tracks drawdowns, and the Steady Growth had a max drawdown of 21.6%, second only to the 25.3% of the 2008 crisis.

- My max drawdown was around 11.5%, so again I beat my “benchmark”.

Quick Links

I have just three for you this week:

- The Economist reported that US trustbusters have forced Visa to back off Plaid

- The UK Value Investor reported on the performance of his portfolio during 2020

- And Alpha Architect wrote about the definitive study on Long-Term Factor Investing Returns.

Until next time.