Weekly Roundup, 17th November 2015

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup in the FT, with Jonathan Eley.

Contents

Care homes vs retirement flats

Jonathan was contrasting the sale prices of retirement flats with regular property:

- new 2-bed retirement flat, seaside town in southeast England, £275K @ £472 per sq ft

- regular bungalow in the same town, with garden and parking, £250K or £338 per sq ft

The retirement flat also comes with a £3K pa service charge.

McCarthy and Stone – recently re-floated at a small loss after 9 years of ownership by a private equity firm – sells retirement flats at premium prices.

It has 70% of the market, and claims the optimisation of the flats for older people with decreasing mobility justifies the premium. Its margins and return on capital are 20%.

Four Seasons on the other hand, is a care home operator that is still owned by private equity. It has debts of £500M and is struggling.

We saw last week that the demographics for care homes should be very favourable, but in the UK the system works against them.

Four Seasons is loss-making because most care is paid for by local councils. Budget cuts have forced down the fees they are willing to pay, and the numbers they judge worthy of care.

In response, care homes are jacking up fees to self-funding clients to cover the shortfall. In turn this drives down demand from private clients.

Care homes costs are also rising as the new minimum wage comes into force and visa restrictions hamper importing cheap nurses from the Philippines.

Last of the tax loopholes

Naomi Rovnick looked at one of the lesser known tax reliefs in the UK.

Loopholes are in general being tightened:

- HMRC has been cracking down on film finance schemes

- narrower investment criteria for EIS and VCTs have been introduced

- EIS now excludes solar and wind power generation (see below)

One relief that remains is business property relief (BPR), which can be used to mitigate inheritance tax (IHT). This involves investors becoming part-owners of an unlisted company. ((Note that there are usually high fees involved – 3% to 5% up front and 0.5% to 2% pa – I am not recommending these schemes ))

Low risk businesses with steady cash flows are preferred for both EIS and BPR, and indeed many schemes layer BPR on top of EIS schemes after a qualifying period.

Popular investments include:

- leasing street sweepers or refuse collection vehicles to councils

- leasing MRI scanners and ambulances to the NHS

- crematoria

- pubs, restaurants and hotels

- agricultural assets like forests and farms

- self-storage units

Some analysts have warned that demand for these assets could be hit by any increase in IHT allowances, or if IHT was scrapped altogether.

For most people, SIPPs and their primary residence will be simpler and less risky ways of passing on money to their children.

Green energy tax relief axed

Adam Palin had more detail on the Treasury’s decision to exclude renewable energy from tax reliefs.

As well as exclusion from EIS from 30th November, schemes owned by community groups will no longer qualify for social investment tax relief (SITR).

As recently as the March Budget, community energy generation had been explicitly exempted from the wider exclusion of renewable projects.

Jan-Willem Bode, CEO of Mongoose Energy, which raises finance for community schemes, said that the change would not stop the development of the sector.

Even without the tax relief, most projects deliver returns of around 7 per cent a year.

Women to sue over pension age change

Josephine Cumbo reported on a threat by hundreds of thousands of women to sue the government over increases in their state pension age.

The changes are “coming out of the blue” said a spokesperson for the ironically titled Women Against State Pension Inequality (Waspi).

I can’t say I have much sympathy. It was never clear to me why women, who traditionally worked fewer years than men yet live much longer, were ever entitled to receive their pension earlier.

Unfavourable demographics mean that the State Pension will be an increasing burden on the taxpayer as time goes by. The qualification age is heading in only one direction, and that is upwards.

I have personally had one year added to my state pension age, and in 2010 I came within 6 months of accessing my private pensions before the government added another 5 years on to my qualifying age.

The specific changes to equalise ages between men and women were first announced in 1995, so anyone who is surprised by them must have been living under a rock.

The legal basis for the women’s claim appears to be the fact that they didn’t receive a letter informing them about a decision by the coalition in 2011 to speed up the equalisation.

Originally it was planned to complete by 2010 but it will now happen by 2018. An increase for both sexes to 66 by 2020 was also added.

The Department for Work and Pensions has said that it did notify the women.

The continuing debt crisis

The Economist had a couple of articles about the continuing debt crisis, which has spread from America to Europe and now finally to the emerging markets.

- Investors have already dumped assets in the developing world, but the slowdown is to come.

It should be less severe than those in the 1980s and 1990s that were triggered by defaults and broken currency pegs.

- Emerging markets now have more flexible exchange rates, bigger reserves and fewer debts in foreign currency.

But it will weaken the global economy as the Fed starts to raise interest rates.

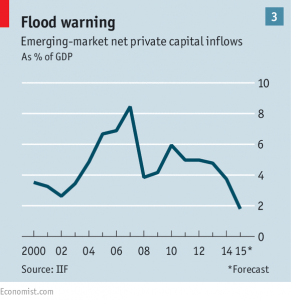

All three legs of the cycle began with capital inflows which drove interest rates down, leading to credit growth.

- Since the busts in the West, capital has changed direction and headed to poorer countries.

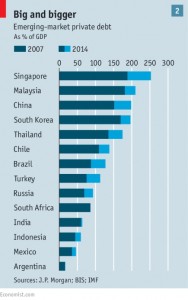

- Debt in emerging markets has risen from 150% of GDP in 2009 to 195%

- Corporate debt has grown from less than 50% of GDP in 2008 to almost 75%.

Now the strong dollar and the prospect of higher American interest rates mean the flows have stopped. The question is whether we are due a slowdown or a bust (recession).

The newspaper splits emerging economies into three groups:

- hangover, not heart attack – South Korea, Singapore, China

- China has an enormous current account surplus and $3.5 trn in FX reserves, around three times its external debt.

- The authorities will be able to bail out borrowers and avoid defaults.

- Creating zombies and non-performing loans will slow growth but prevent a crisis.

- countries without these defences – Brazil, Malaysia, Turkey

- Brazil has a current account deficit and relies on foreign capital

- Malaysia’s banks have lots of foreign liabilities, and its households have the highest major emerging market debt-to-income ratio; it has few FX reserves and its current account surplus will shrink

- Turkey has a current account deficit, high inflation and lots of foreign currency debts

- those that will escape or have already suffered – India, Russia, Argentina

- the rouble has already devalued and the economy may be responding

- Argentina has little debt but needs a new reformist president

The developing world now accounts for more than half of the global economy (58% at purchasing power parity – PPP) and the slowdown will hit global growth in 2016.

Europe is exposed to this and more monetary easing is likely. The US has more to worry about.

Decoupling will put upward pressure on the dollar, hurting exports and earnings. And waves of capital may again target the American consumer as “the borrower of choice”.

This would bring the crisis right back where it started.

A regulator reflects

[amazon template=thumbnail&asin=0691169640]

The newspaper also reviewed a new book on the financial crisis, by a British regulator.

Between Debt and the Devil: Money, Credit, and Fixing Global Finance is written by Adair Turner, one of the regulators who had to deal with the fallout from the 2008 crisis.

Turner is a former management consultant, investment banker and head of the CBI. More importantly, he became head of the FSA in September 2008, a few days after Lehman Brothers collapsed.

He admits that he did not see the crisis coming.

He believes the problem lies with credit creation.

Banks are supposed to take deposits from consumers and lend them to businesses. In practice, an increasing proportion of lending is against property – 30% in 1928, rising to 60% by 2007.

So cutting interest rates won’t stimulate the economy, as new credit is used to chase up the price of existing properties, rather than buy new assets.

This can lead to an asset bubble. When it bursts, bad debts are created – a debt-deflation cycle.

Further, the gains from the rising asset prices go to the wealthy, who don’t spend as much. This slows the growth of the economy, unless the middle classes and the poor borrow money to maintain their

standard of living.

Which is the start of the next crisis.

Before 2007 regulators and economists saw debt as a zero sum game. They have since tried to stabilise the system by making banks hold more capital.

Turner thinks that “Free financial markets left to themselves are bound to … generate unstable booms and busts”. He favours restrictions on private credit and the creation of money by the central bank to finance a budget deficit.

This is both the policy that led to hyperinflation in Wiemar Germany, and also the “people’s

quantitative easing” proposed by Corbyn. But for Turner, the alternatives are stagnation or boom and bust.

I don’t know where we’re heading, but I wouldn’t start from here.

Bonds that take a hit

Sticking with the theme of debt, Buttonwood reported on a new type of bond that is designed to take the hit when banks fail.

Banks lend out much more money than they have capital to absorb losses. When loans go bad, they can easily go bust.

In 2008 governments mostly bailed them out (because without the banking system you don’t have an economy). Next time they’d rather not.

The Financial Stability Board (FSB – an international regulators body) wants bond holders as well as equity holders to take a hit. They expect the threat of a potential loss to make bondholders keep a close eye on whether the bank’s management is taking on too much risk.

But this can’t be done at a stroke. If the banks flood the market with new bonds, the cost of borrowing would rise. As an alternative banks could improve their capital ratios by lending less, but this would hit growth.

So it will only apply to “global systemically important banks (GSIBs) and it will be phased in.

Banks will need to have 16% of risk-weighted assets in “total loss-absorbing capacity” (TLAC – equity plus the new debt) by 2019, rising to 18% by 2022.

Investors will want a higher yield on TLAC bonds, which will lead to higher lending rates, and slow growth. FSB expects the impact to be a few basis points.

TLAC bonds could also provide early warning of the next crisis, since they are riskier. But bond markets are increasingly illiquid and prone to spikes.

So we might see a few false alarms before the next wolf appears.

Sharp elbows

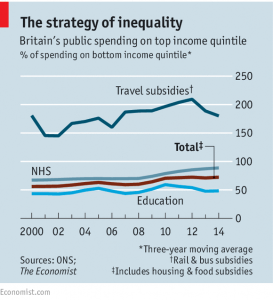

The Economist also looked at claims that the rich in the UK are grabbing a larger share of public spending.

This appears to be what the newspaper calls “half-right”, the poor still get more than the rich, but after “adjusting for need” the rich get more than they are due. ((This sounds like Labour’s use of “relative poverty” to justify 50-inch TVs and taxis to the supermarket for the unemployed ))

The average household in the UK gets benefits worth £7K a year. The main ones are:

- the NHS (20% of all government spending)

- education

- transport subsidies

Over the past 15 years, the richest quintile’s share has increased from 56p per £1 spent on the poorest quintile, to 73p today.

The key drivers are:

- the elderly are getting richer, and they are the main beneficiaries of the NHS

- the average pensioner’s income has risen from 86% of the median in 2000 to 100% today

- even amongst workers, the 27% extra that the bottom quintile received in 2000 has disappeared

- this appears to be the result of middle-class families dumping their private health insurance in favour of the NHS, plus a reduction in GPs in poor areas

It’s hard to not see these changes as being largely needs-driven.

Against the trend, fewer people are sending their kids to private school (down from 7.2% in 2008 t0 6.9% today) but spending on education has improved for the poor:

- in 1977 the richest quintile received 87p for every £1 spent on the poorest quintile, but last year it was 48p

- this reflects the massive increase in higher education, which is no longer a privilege for the rich

- it’s also because of the introduction of higher tuition fees and subsistence loans (poor students get a grant, and relaxed loan payment terms)

Transport is the most regressive service – the rich receive almost twice as much as the poor.

- this is because they travel more, often on expensive inter-city trains (five times as far as the poor)

- they also drive three times as far – poor people use buses, which are less heavily subsidised

Spending on the NHS and schools (as well as pensions, foreign aid and defence) is ring-fenced from cuts.

So maybe transport subsidies will be where the axe falls.

Oil

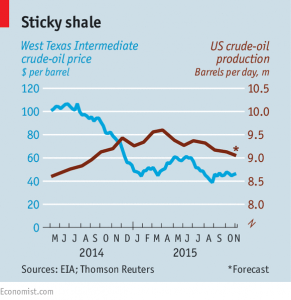

The newspaper also had a couple of articles about oil. The first was about oil prices finally responding to supply and demand, rather than OPEC manipulation.

For the whole of my life to date, the oil market has been a cartel market. But not now.

Saudi Arabia has resisted moves by the rest of OPEC to reduce production in order to force prices up. Saudi wants the current low prices to bankrupt its competitors, particularly the US shale oil producers.

In the meantime, It has used its low production costs to grab a bigger slice of a cheaper pie, stealing mostly from Russia.

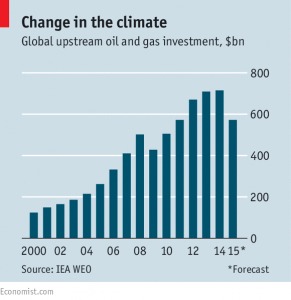

Other countries and the big listed oil firms have higher costs and have cancelled $150 bn of investments, with more to come.

For now, higher production from existing facilities will compensate, but eventually production will fall.

The low price is boosting some aspects of demand in the west (larger vehicles etc.) but energy intensity (oil consumed per unit output) is falling. “Peak demand” is replacing “peak oil” as the industry buzz phrase.

Shale is behaving oddly. Production has only just peaked, and it’s hard to predict how it might respond to higher oil prices.

The oil price might recover in a year or two, or stay low for a decade.

The second article was about how some of the oil majors are ducking the global warming challenge.

Since the 1990s they have been “encouraging debate” about climate change, whilst simultaneously investing in renewables. When the 2008 crisis drove up oil prices they reversed this strategy.

But now the fall in the oil price has led to big exploration projects being abandoned. High cost reserves in the Arctic, Canada, North Sea and Gulf of Mexico will be ignored.

Ahead of a Paris summit on climate change negotiations, oil men are concerned that the proposals tabled for discussion would impact demand for fossil fuels.

Exxon Mobil thinks that they will make up 75% of total energy demand even in 2040, only slightly below their current share. But the International Energy Agency (IEA) thinks they will be down to 60% by then.

Oil companies outside the US are officially behind the campaign to limit global warming to two degrees celsius, and are investing again in natural gas – which produces less CO – and renewables.

BP’s chief economist recently estimated that the world had almost three times the reserves that it could burn in meeting on the two degree goal.

The industry sees three ways to stay in the game by reducing emissions:

- substitute gas for oil in power generation

- improve energy efficiency (fuel consumption)

- prevent so much methane leaking out of wells and processing plants

They would also like to see a “carbon tax” introduced. Cynics argue this is because it would hit coal much harder than gas, speeding the change within power-generation.

Trans-Pacific Partnership

Finally, the Economist looked at the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TTP), a 6,000 page trade deal between the US and 11 other countries. It’s intended to lead to a boom in services, but this might take decades to happen.

Over it’s first 10 years it’s expected to boost trade by $300bn ($30 bn a year). Over the ten years to 2013, annual growth averaged $1 trn.

TPP cuts tariffs for cars and agriculture, but is mostly concerned with “non tariff barriers” – customs procedures, “buy domestic” rules for government, and regulatory barriers against services.

Finance, telecommunications, education and health care are increasingly tradable thanks to new IT. They account for a large share of GDP in most rich countries, but almost no trade at the moment.

The paper imagines hospitals in America outsourcing “patient monitoring to nurses in Malaysia, diagnostics to technicians in India, and consultations to doctors in Canada”.

Unfortunately trade generally grows with GDP, and rich world GDP growth is likely to be modest in the near future.

An exception was the 1980s, when trade grew twice as fast as GDP, thanks to “a revolution in supply chains that had been decades in the making”.

This was the introduction of “intermediate goods” to the raw materials and finished goods that were already traded, and it depended on several earlier revolutions that took a long time:

- tariffs falling

- containerised shipping

- cheaper long-distance phone calls

- China opening up economically

As America and China keep more of their supply chains to themselves, growth in trade is now slowing again.

For a services trade boom to happen, several things need to fall into place:

- tariffs need to come down

- mutual recognition of professional certifications needs to happen

- the TTIP (US – Europe services trade pact) would help

- so would advances in digital translation

So don’t hold your breath.

Until next time.