Weekly Roundup, 21st November 2017

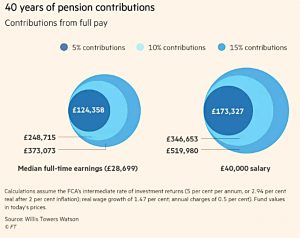

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup in the FT, with an article about how much you need to save for retirement.

Contents

How much is enough?

There’s not too much to write about today, as most commentators are focused on Brexit and the Budget (which we’ll cover later in the week).

In the FT, Josephine Cumbo wrote about how much people need to save for retirement, but the double page spread didn’t answer the question definitively.

- As you would expect from the FT these days, there was a lot of focus on the difficulties that millennials have in saving.

Not that these aren’t real, of course – house prices are very high and graduates today have debts my generation didn’t.

- DB pensions have been replaced with DC schemes and the state pension age is receding into the distance.

But we all know that by now, and reiterating the problems doesn’t solve them.

The full state pension is now £8.3K, but most people will want two or three times that much for a comfortable retirement.

Workplace auto-enrolment has been introduced, but the contribution levels are too low to provide a big enough pension pot.

- They are currently 2%, rising to 5% and then 8% over the next couple of years, and only apply to earnings between £5,876 and £45,000.

A recent report by the Pensions and Lifetime Savings Association (PLSA) – which we covered here – suggests that only 16% of savers knew how to achieve their desired standard of living in retirement.

- The PLSA thinks that 13.6m UK workers are at “high risk of failing to achieve an adequate income in later life”.

The PLSA suggested that mandatory automatic enrolment contributions of 12% would be needed to give medium-earning millennials a chance of a decent retirement income (close to the TRR – see below).

According to the FT, the three key numbers in pension saving are:

- how much (%age of salary)

- how soon (what age do you start saving)

- how long (will your retirement be)

I think (high) investment returns, (low) costs and (low) taxes are three other numbers to consider.

- So make sure your savings aren’t in cash, find a cheap platform, and take advantage of SIPPs and ISAs.

The Pensions Commission suggests a “target replacement rate” (TRR) of two-thirds of salary in order to enjoy a similar standard of living (with lower outgoings in retirement).

- So someone on £25K would be aiming for pension income of £16.7K.

- That means they need a private pension income of £8.4K alongside the state pension of £8.3K

According to the FT, current annuity rates mean that at 65 they would need £327K to get £10K of index-linked income.

- I would argue that this is such bad value that no-one should be buying an annuity.

The International Longevity Centre (ILC) reckons that you need to save 18% of salary each year, which sounds in the right ballpark to me.

- Aviva suggests savers should aim to save at least 12.5%.

Another rule of thumb is to save 10 times your annual salary before retiring.

I would run the calculation in the opposite direction:

- Using a safe withdrawal rate (SWR) of 3.3% means that you need a pot that’s 30 times larger than your planned living expenses in retirement.

Using the two-thirds rule for the TRR, that would be 20 times your salary, rather than 10 times.

Of course, each magic number depends on all the others.

- The sooner you begin, the less you need to save (because of compounding).

There’s also an increasing trade-off between working longer and contributing more, as life expectancy (and therefore the length of retirement) has increased.

How to be a pension millionaire

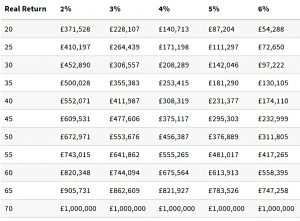

In City AM, Katherine Denham had an article on a related theme:

Since the LTA is currently £1M (this week’s looming budget not withstanding), this also works as a guide on how to avoid paying the 55% tax surcharge.

The article notes the Barclays Equity Gilt Study average UK stock return over the past 116 years of 5% pa, but provides tables of “stop now” numbers for:

- projected real returns between 2% and 6% pa, and

- ages between 20 and 70

There are four tables, one for those who want to retire with £1M at age 55,

- and others for those who want to retire at 60, 65 or 70.

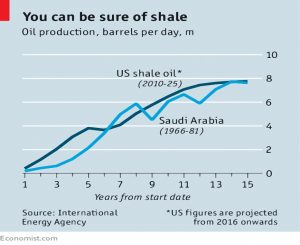

The oil market

The Economist reported that the oil market has got ahead of itself.

- Brent crude futures hit a two-year high of $64 a barrel on November 7th, before falling back to $62.

There was also a sharp drop in metals over concerns that demand in China was slowing.

- High-yield corporate bonds also weakened significantly.

Fears over instability in Saudi Arabia seem to have receded.

But the key factor probably remains shale production.

- The IEA forecast that shale-oil production will exceed that of Saudi Arabia in the 1980s would mean that the price is unlikely to rise in the long-term.

Mugabe

The Economist also looked at the army coup in Zimbabwe.

- After 37 years of misrule, the tipping point appears to have been Mugabe revealing his intentions to install his much younger wife as his successor.

- The Economist drew parallels with Caligula wanting to make his horse consul.

At the time of writing, 93-year-old Mugabe is resisting being sacked as President by his own party.

Leaving aside the current politics, these developments provide an opportunity to review Mugabe’s greatest hits:

- He crushed a rival ethnic group, torturing and murdering civilians.

- He spent public money on patronage and unaffordable services until it ran out.

- Then he seized private property, redistributing white-owned farms to his supporters.

Ignoring property rights lead to foreign investors fleeing.

- He then printed money to pay the army and civil service, leading to hyperinflation.

- Next he used price controls, which meant that shops ran out of basic goods.

A nightmare indeed, but one that is more possible here in the UK than you might think.

- Price controls and seizing private property are back on the political agenda for the first time in 40 years.

- And printing money to pay for public services is also Labour policy.

As JK Rowling said, Corbyn is not Dumbledore.

- And we must trust that McDonnell is not Mugabe.

Art market

Over on Pragmatic Capitalism, Cullen Roche wrote about the record art sale price ($450M) achieved by a dodgy Leonardo portrait.

Perhaps there is a structural problem with the way we value things in our society which reinforces the inequality that is contributing to stagnant growth.

Cullen is upset by the lack of value provided by this transaction:

People have so much money that they will spend half a billion dollars on a painting that they will very likely hermetically seal and place in a vault. It won’t even sit on a wall so its owner can enjoy its intended purpose – to be looked at.

I agree with Cullen that the money would be better invested in productive opportunities (via corporations), but sometimes there just aren’t any sensible opportunities around.

- Rich people have to store their excess consumption capacity somewhere, and the buyer must believe that the scarcity value of this painting (the only Leonardo in private hand) provides security.

If the wealthy value pieces of paper more than productive investment, what are we to do about that?

Cullen thinks that the well-off should just give their money away, and maybe they should.

- But it’s their money, and their choice.

Twitter pics

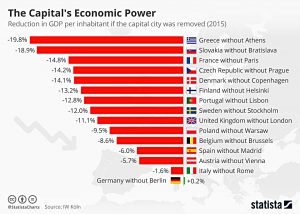

Another quiet week on Twitter, with only three pictures to share.

The first shows the impact on GDP of removing various European capitals from their host country.

- Surprisingly, London is only in the middle of the pack, with an 11% reduction.

- Paris is worse (15%) and Berlin is actually less productive than the rest of Germany.

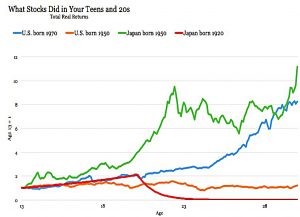

The next one shows the potential effects of stock marking “imprinting” during your teens and twenties:

- Americans born in the 1970s are likely to be more optimistic than those born in the 1950s.

- Similarly, Japanese born in the 1950s are likely to be more optimistic than those born in the 1920s.

I expect to see similar effects from the 2008 crash start to emerge in the coming years.

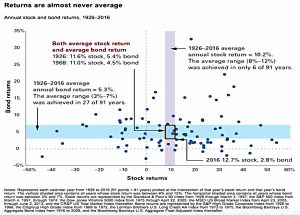

The final picture shows the variability of returns from bonds and stocks, and reinforces the message of wide diversification.

Until next time.