Weekly Roundup, 18th March 2015

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup as usual in the FT, with the Chart That Tells a Story.

Contents

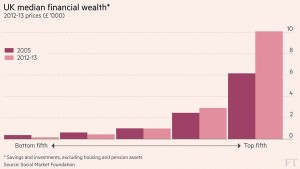

UK median financial wealth

Except that this week it doesn’t really. The chart shows how wealth changed from 2005 to 2013 for the income quintiles in Britain, and purports to show that the rich have profited at the expense of the poor. This may well be true, but by excluding pensions and property from the calculations ((I estimate that more than 70% of my net worth is in pensions or property, and I’m sure I’m not alone in this)) they are presenting a very misleading picture.

The top quintile now has an average £10K of savings, and the bottom fifth almost nothing. While this gap may appear significant to many, in the context of lifetime savings it is not. Based on today’s annuity rates the rich would have a retirement income a massive £200 per year higher than the poor. Looking at this chart, the only conclusion can be that everyone needs to save (a lot) more.

Escape tax-free to Portugal

Merryn has come up with a great wheeze for getting hold of your pension tax-free. There are three legs to the methodology:

- HMRC treats all withdrawals from a pension as income to be taxed at your marginal rate

- Portugal has a tax scheme where foreign pensioners pay no tax on their pension income

- Portugal also has a double-taxation treaty with the UK – if you live in Portugal then you only fall under the Portuguese tax system

The idea is to buy a nice flat in the Algarve for £150K or so ((Sterling is already up 8% against the Euro in 2015, so you will get more for your money than you did last year)) and hang out there for a couple of years whilst withdrawing all the money from your pension.

It’s an attractive idea and I hope someone gives it a go before the loophole is inevitable closed. But it’s not the complete solution. Once you have your cash mountain, you have to decide what to do with it in order to fund the rest of your retirement.

So unless you fancy becoming a buy-to-let baron, it might not be so clever after all. At £15K per year, a decent-sized pension would take quite a while to drip-feed back into the tax shelter of an ISA.

Keeping the poor in the city

Kate Allen had a feature on how to solve the housing crisis in cities. She came up with a seven point plan:

- Demand controls: this effectively limits debt-to-income ratios for borrowers. It is used in Hong Kong and South Korea. Other countries have limits on the loan-to-value measure, meaning buyers need a larger deposit. The UK moved towards this with the Mortgage Market review in 2014.

- Supply controls: supply is determined by planning permission, which greatly increases the value of land. If this uplift was captured by the state and diverted to more housebuilding, a virtuous circle might begin.

- Remove the market: in countries like Singapore, 80% of housing is built by the government and leased to the occupiers.

- Remove spatial restrictions: this is really a variation on supply controls. Abolishing the green belt would greatly increase the supply of housing close to London.

- Encourage renting: renting is popular in Germany and the US. To make this work usually requires some kind of ring-fencing of the rented properties and no tax breaks for home ownership.

- Build elsewhere: in the context of London, this is the Garden City / CrossRail approach. Lower-paid workers can live in a nice area, but with a fairly serious commute.

- Subsidise ownership: this includes schemes like the current Help to Buy and also the part-ownership schemes of the past 20 years.

- Proposal 1 is fine morally, but can paradoxically exclude the young (who are often also the poor)

- Proposal 2 is a good idea, but the urban sprawl seen in the West of the US or in Japan needs to be avoided. Concreting over the green belt would not help in the long run.

- Count me out on Proposal 3 – anyone who prefers UK council housing to private property is welcome to it.

- I am also against Proposal 4 – as Kate points out, Houston (with no zoning laws) is twice as big as New York but has only a quarter of its population. Urban sprawl also leads to the domination of the car, which is the opposite direction from the one we are headed in.

- Proposal 5 is also a bad idea – apart from improving job mobility for the young, renting encourages a short-term approach to life, and discourages aspiration and self-growth.

- Transport is key to Proposal 6 – if CrossRail is a success and similar high-speed lines can be built to new towns 20 miles from London, it has a chance.

- Proposal 7 is fine as far as it goes:

- It will only ever help a minority, and will only push up demand for the rest.

- While it is important to get young people onto the housing ladder, those it helps will often be the ones who will remain stuck on the first rung.

- It’s also important to remember that schemes like these were largely responsible for the 2007-08 subprime crisis in the US.

It’s clear that there is a problem with housing supply in the UK, particularly around London. I’m a big fan of the idea of converting Manchester into the famous “Northern Powerhouse”, but whether the populations of Liverpool, Leeds and Sheffield will ever accept this in unclear.

Diverting economic activity and population to the North would help, but London will always need an army of the lower-paid to perform basic tasks. The idea that these people can live in central London is naive. We need to build the new Garden Cities, and make sure that the transport out to them is world-class. There’s a lot riding on CrossRail.

Traded annuities 20% discount

As I write just before the Budget speech, everyone seems certain that the new pension freedoms will be extended to those recently trapped in annuity contracts. The details are unclear but the basic idea is that insurance companies would buy up annuities in bulk to offset the mortality risk associated with individual policies. It’s possible that fund will spring up as in the US, but single annuities would be unsuitable for individual investors.

Josephine Cumbo reported on the other side of the equation, quoting Legal & General that sellers could expect to return their annuities at a 20% discount to the price they paid for them. In addition to this, money already paid out since the purchase would be deducted. It may still make sense for some who really need the cash, but it doesn’t sound attractive for the majority.

Art index passes pre-crisis peak

James Pickford wrote that art prices have passed their 2008 pre-crisis peak, having fallen 30% from that high. Art has outperformed wine, jewellery, coins and antique furniture, rising 15% in 2014, compared to 10% for the Knight-Frank luxury index as a whole. Over ten years, art is up 252% and is behind only classic cars (up 16% in 2014 and up 487% over the decade).

US pop art was the best sub-category, up 86% in a year and 351% over 10 years. This is partly explained by a lot of the buying money coming from the US, and new buyers from South America, the Middle East, China and Southeast Asia moving on from their home markets. New works now fetch higher prices than old ones, though this has happened before, during the nineteenth century with the Pre-Raphaelites.

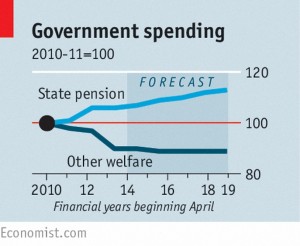

Pensioners hit back

Not for the first time, the letters page of the Economist was full of angry responses to the newspaper’s proposals that pensioner benefits be means-tested or withdrawn. There were even letters of a similar tone in The Guardian. Amongst the points made by the correspondents were the following:

- British state pensions are amongst the worst (lowest) in the developed world already – France pays £15K and Spain £26K, against a maximum £7.5K under the new UK system

- Cuts would impact the prudent (those who sacrificed consumption when they were young) and not the profligate, and send a message to the young to not bother to save

- Old people (as parents and grandparents) support the young already

- Those deprived of bus passes will use cars instead

- The return on pensioner’s savings has been wiped out by low interest rates, which subsidise young people’s mortgages (an average transfer of more than £1,000 per household per year)

Let’s hope this particular bee in the paper’s bonnet dies with the forthcoming general election.

Big firms pay less

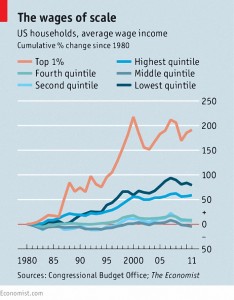

Elsewhere the paper claimed to have explained in part the rising wage inequality in the US over the past 30 years. Similar trends are found across the globe, despite differing policies on taxation, the minimum wage and corporate pay. This is generally explained by technology driving up the premium for skilled workers, but a new paper (which initially uses data from the UK) suggests it may be because the size of firms is increasing.

Large firms benefit from economies of scale, and should be able to pay everyone more, but increasingly they do not – gains are concentrated at the top. The authors offer two explanations:

- automation is easier for larger firms, and so they can resist wage demands from unskilled workers

- middle-income workers will accept lower pay today from a large firm where their long-term prospects are better

Looking at data from 15 OECD countries from 1981 to 2010, the authors found that increasing levels of inequality were linked to increasing size of companies, particularly in the US and in Britain. Denmark and Sweden have seen less growth in the size of firms, and less inequality.

A second paper suggests that firms will become even bigger, since their greater productivity raises barriers to entry for competitors. This is not all bad, since bigger firms invest more, stimulating growth. The small size of firms in Greece, Italy and Portugal is thought to hold back those economies.

But it seems that growth will come with more inequality, unless small firms can be encouraged. The most obvious way of doing this is to increase their access to credit.

Paying for long-term care

Finally the paper looked the options for paying for long-term care. The statistics are sobering:

- one in three will develop dementia

- one in six will end up in a care home

- almost half will need care of some kind

- the average stay in a care home is 17 months and costs £57K

- the highest bills are around £200K

Under the current regime those with less that £23,250 in assets are paid for, but everyone else must self-fund. From next year the means-test (mean-test?) threshold will rise to £118K and there will be a cap on personal contributions of £72K. Unfortunately the cap does not include “hotelling” costs (bed and board) which can typically add another £40-50K, and in the worst case another £70K.

The government had hoped that a market in care insurance would develop, but people are over-optimistic about their health, and the contribution from the NHS. Insurance companies are pessimistic, and the insurance is therefore expensive. Some old people also fear their children will abandon them if they are insured.

This is a story without a happy ending.

Until next time.