Weekly Roundup, 14th November 2017

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup in the FT, with the Chart That Tells A Story. This week it was about the effect of Brexit on the FTSE indices.

Contents

Footsie and Brexit

Ed Bowsher looked at what’s been happening to the UK stock indices “recently”.

- The FTSE-100 closed last week at a new high of 7,572.

- But it’s only up 9% over the past 18 years.

The FTSE-250 is up 215% over the same period.

- Smaller companies find it easier to grow than large companies, and there has been persistent outperformance from small caps in stock markets.

- And the FTSE-100 was overvalued at the start of the period in question.

It was the height of the dot com boom, and even though most of the companies directly involved were small, the euphoria was contagious and the FTSE-100 got swept up into the party.

Since Brexit, the major index has done better (though you would struggle to see that from Ed’s chart).

- That’s because the stocks are more international in terms of their earnings, and sterling has fallen since the Brexit vote.

I built my own chart (in Google Finance) to make things clearer.

- Interestingly, the AIM index (AXX) has done much better than the FTSE-250 (MCX), the All-Share (ASX) and even the FTSE-100 (UKX).

I don’t have a clever explanation for that one.

Ed recommends hedging your bets on the outcome of Brexit by investing in both the FTSE-100 and the FTSE-250.

Buy-to-let slowdown

Our second FT chart of the week comes from James Pickford, who identified the first signs of a buy-to-let slowdown.

- Growth in BTL mortgages is now lower than the general level of new mortgages, after being higher over the previous decade.

- This is seen as evidence that investors are starting to rationalise their portfolios.

And things are only likely to get worse for BTL investors, with rising interest rates, more cuts in tax relief and potentially falls in capital values.

Are we there yet?

The FT had three articles on whether the bull market would continue, or a crash or crisis is just around the corner.

First up was Ken Fisher, who recently gave a talk at a readers’ event.

- As you would expect, Ken remains bullish.

He thinks (like me) that markets are still in the “optimism” phase, with “euphoria” yet to come.

- He thinks that we have three to four more years.

- I think we could have six to 18 months, but let’s see.

He recommended that people focus on high-quality, liquid investments which would go up the most during the euphoria, and be the easiest to get rid of when it ends.

- Tech, healthcare and the “growth-oriented parts of finance”(?) were his sector picks.

- Energy and retail were to be avoided.

He is underweight the US and overweight Europe and Emerging Markets.

He isn’t worried about high debt levels at the moment, because low interest rates mean that their carrying costs are low.

He also thought that Brexit would take much longer than people thought, and he warned people away from IPOs.

Martin Wolf wrote about the “omnibubble”, in which prices of all assets are high.

The CAPE (which I think has dubious predictive power in recent decades – see below for more on this) shows that US stocks are very expensive, Germany’s are less so, and arguably UK stocks are slightly on the cheap side.

- Japan’s stocks are even cheaper.

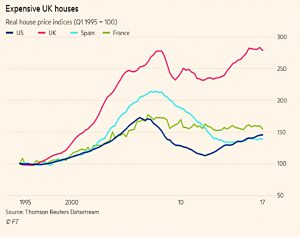

UK houses are expensive, US ones less so, and Italy and Spain’s property is even cheaper.

Bonds are also expensive, as shown by the decline in the real yield on safe bonds.

- In the 1980s the real yield on UK Gilts was 4% pa, but it has been negative since 2011.

20-year US inflation-linked bonds yield 0.5% pa, and most rich countries can borrow for 30 years for between 1.1% (Germany) and 2.8% (the US).

These low real interest rates on safe assets underpin high valuations everywhere.

- Martin suggests that perhaps only US stocks are truly in a bubble.

So the question is how long these low interest rates will last.

- The answer depends on whether you think that central bank manipulation is responsible.

If so, then changes to monetary policy could burst the bubbles.

- But Martin suggests that real interest rates must reflect economic conditions (low productivity, low inflation, a “savings glut”).

And therefore it might take decades for these conditions to unwind.

- He even says that “it is possible that things are a bit different this time”.

Let’s hope so.

Saudi Arabia

John Authers looked elsewhere for the next crisis – to Saudi Arabia in fact.

- Unlike government reshuffles in perennially unstable countries like Japan and Italy, the impact of the Saudi crackdown constitutes one of Donald Rumsfeld’s “unknown unknowns”.

There has never been a change of power in Saudi Arabia, hence its institutions are untested.

- Understandably, the oil price has spiked.

More unusually, the recovery in oil prices in recent months hasn’t had the usual effects:

- the dollar hasn’t crashed, nor emerging markets currencies risen

- the recovery in energy stocks has been lukewarm

It could be that oil doesn’t matter so much anymore.

- Its share of global GDP has fallen from 7.5% at the start of the 1980s to only 2% today.

Another explanation is that China underpins demand for commodities and hence growth, which means that the impact of a price shock is reduced.

- Continuing liquidity from the ECB and the Bank of Japan also helps.

As with North Korea, the probability of a continued status quo is more than that of a disaster (in the case of the Saudis, war with Iran or total collapse of the governing system).

CAPE

Over in the Economist, Buttonwood looked at the CAPE measure that’s currently being used to value stock markets.

- The CAPE is not much use as a short-term indicator, as it can be well above the long-term average for years before anything happens.

But a new paper confirms that it works over a period of a decade or so.

At the same time, removing the hindsight bias (investors don’t know where in the range they are when they buy shares) reduces the outperformance (8% pa from best to worst quintile) by more than 1% pa.

- That still leaves plenty to shoot for.

Buttonwood also questions the data:

- 146 years of US earnings numbers provide only 14 completely independent decades for comparison

So the current projection of 10-year real returns from US stocks is 2.6% pa (low)

- But the confidence range is -3.4% to +8.7% pa (which is pretty wide).

A better argument is that since earnings (relative to GDP) and valuation multiples are both currently high (to produce the high CAPE), there is only one realistic direction of travel, barring an unexpected rapid growth in GDP.

- This tells us nothing about timing of course.

The authors also note the comparatives effect:

- Not just stocks are expensive – yields on bonds and cash are low.

- Even with the high CAPE, returns on stocks should be higher than those on bonds and cash, so they remain a sensible (though expensive) purchase.

Buttonwood calls this the “least dirty shirt” on offer.

I guess the way I feel about the CAPE is that it’s not a bad indicator that it might not be the best time to plough lots of new money into a stock market.

- But it doesn’t work so well as an alarm bell ringing to get you out of a raging bull.

ICOs

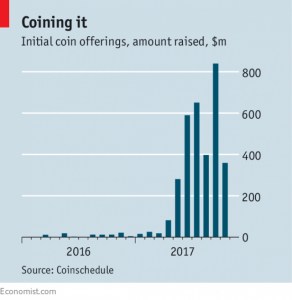

Sticking with the theme of bubbles and high valuations, the Economist had two articles (1 and 2) about initial coin offerings or ICOs.

The one place in the markets where I do detect euphoria today is cryptocurrencies, and the frothiest part of the crypto arena is ICOs.

- Bitcoin itself is up 600% in 2017 to date (and was up 700% last week).

ICOs are a form of crowdfunding where existing crypto (usually ethereum) is swapped for more esoteric tokens.

- They have raised $3.2 bn this year, comparable to the amounts raised by VC for internet startups.

Most of the schemes operate like advance payments into a loyalty scheme for the new firm’s products, but the investors treat them like new versions of the gold mine that bitcoin has proved to be.

- They are unregulated, and have already been banned in China and Singapore.

The Economist sees parallels with the railway mania of the 1840s and the dot com boom in the 1990s:

- Perhaps after the “dust from the bust” settles down, some good will come from the boom.

The newspaper sees the new firms as cooperatives, where owners, workers and customers all have their interests aligned.

- They have decentralised control, scale economies and low transaction costs.

I’m not convinced yet, and other than arms-length speculation on BCH and ETH (via spread bets), I’m staying away from crypto for now.

- This is definitely one for the “Do Your Own Research” bucket.

Dream or nightmare

Back in the FT, Jason Butler brought cautionary tales of lottery winners who quickly ran out of cash by spending their winnings too quickly.

- Similar logic applies to the pension pots of retirees.

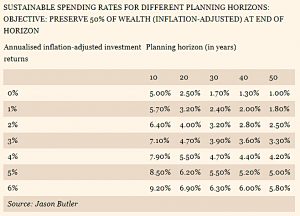

His article contained a potentially useful table of safe withdrawal rates (SWRs).

- Across the top is the time horizon in years (from 10 to 50)

- Down the side is the real rate of return on your investments (from 0% to 6%)

What makes Jason’s table interesting is that rather than preserve the initial capital entirely, or deplete it entirely over the period, he takes a middle route:

- At the end of the period, 50% of the starting capital would remain.

This is not my preferred option, but it could be useful to some readers.

After a bumper crop last week, I’m afraid that I don’t have any Twitter pics this week.

- So that’s it for today.

Until next time.