Weekly Roundup, 19th April 2015

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup in the FT. where Merryn took at look at inheritance tax.

Contents

Inheritance tax

Forty years ago ordinary people weren’t too concerned about IHT (or estate duty as it was called then).

But even though the allowance has increased more than inflation since then – from £15K, the equivalent of £180K in 1972 , to £325K now – the rise in property values, particularly in London and the South East, means that many more people are now liable to pay the tax.

Merryn talks about abolishing IHT, but in fact she wants to replace it with a tax on all transfers of capital, from the living or the dead.

- This is in effect IHT with the loopholes closed – even giving money away seven years before your death wouldn’t protect it.

I’m not a fan of IHT. Your money is taxed once when you earn it (income tax and NIC) and again when you spend it (VAT).

- Taxing it again when you pass it on seems a bit much to me.

Central banks do nothing

Ken Fisher expects the central banks to do nothing this year.

- He doesn’t buy the argument that Mark Carney and Janet Yellen are neutral and apolitical.

With the UK’s Brexit referendum in June and the US presidential election in November, the two central banks should support one another and not risk raising rates around these two big votes.

- Only galloping inflation or a collapsing economy would force them to act, and neither seems likely at the moment.

Which is all good news for stock markets.

Liquidity and benchmarks

Daniel Godfrey took a look at a couple of problems with the investment management industry.

The first is an obsession with liquidity, which he says dents long-term returns.

The second is the cult of benchmarks and minimising “tracking error”.

- Active fund managers worry that short-term underperformance will lead to redemptions, and so they are unable to make decisions with a view to the long-term.

- This in turn leads many company boards and management teams to prioritise short-term performance.

Daniel would like to see more emphasis on research into companies that can create wealth over the long-term, and on close relationships with company management.

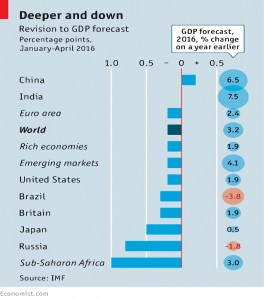

IMF forecasts

The Economist reported on the latest IMF forecasts of GDP.

- Without predicting a crisis or a recession, the tone of the review was negative.

Estimated GDP growth for 2016 is now 3.2%, down from 3.4%, but that would still be better than 2015.

- US, Europe and the emerging markets were all downgraded.

- Africa saw the biggest cut, mostly because of the impact of oil on Nigeria.

- China was not downgraded.

NIMBYs

The newspaper also took a look at what can be done to improve housing in major cities like London and San Francisco.

- Such places are centres of economic activity but this is constrained by the number of people who can live there.

Planning restrictions and environmental concerns alow NIMBYs to thwart new projects.

- The potential migrants who would benefit most from the new builds have no say in their construction.

One option is to bribe locals with some of the extra tax revenue that a new development will generate.

Another way forward is to take decisions at a city-wide level, rather than in the boroughs.

- That way more people who stand to benefit from a development will be included in the vote.

Vertical integration

Schumpter wrote about the revival of an old management idea – vertical integration.

This approach – owning your suppliers and / or distributors – was popular a hundred years ago with car firms, oil companies and steel makers.

- For the last 30 years, the trend has been to focus on a “core competence” and outsource the rest.

- Globalisation and sophisticated markets meant that better suppliers were always available.

Now tech firms like Apple and Tesla are bringing integration back.

- Apple’s focus is simplicity – its customers want something that just works.

- They don’t want to deal with multiple suppliers or components that don’t talk to one another.

- Tesla is integrated because it’s interested in “inventing the future”

- There are no suppliers yet for many of the things it needs.

- A third reason is choice.

- Netflix and Amazon make their own content to be sure that they have a unique offering.

- Speed is a fourth reason.

- Zara has designers, manufacturers and shops. This allows it to get new “on-trend” products into their stores in a couple of weeks.

- And finally there is security of supply in an uncertain world.

- Ferrero, maker of Nutella, also owns the Turkish producer of the hazelnuts it needs.

- IKEA owns forests in Romania and the Baltics.

- Cruise companies own islands in the Caribbean to guarantee unspoilt destinations.

Outsourcing still works for mundane products, but the balance across the board is more complicated than people thought a few years ago.

Assortive mating

In the Independent (online), Hamish McRae looked at inequality, and in particular at the idea that inequality is caused not so much by differences in income, but by who marries whom.

- He was using US data, but from 1960 to 2005, the increase in inequality could be completely explained by the shift to marriages between two graduates.

- Such marriages are now twice as common as they were.

Fifty years ago, men typically married woman with less education and work experience than them.

- As women have become better educated and joined the workforce, more successful people tend to match up with one another.

The problem with this – if you are one of those people who believes that inequality is necessarily a bad thing – is that wealth and education is much more difficult for a government to influence.

- A series of life choices can’t be addressed with a new tax band.

In the UK, the ONS reported than income inequality has barely changed over the past 25 years – post-tax income is actually less unequal than 1990.

- The surge in house prices in London and the South East means that wealth inequality has risen, however.

US pensions bubble

In Money Week, Edward Chancellor begged to differ with Janet Yellen that the US is not a “bubble economy“.

- Janet means overvalued assets, driven by increasing credit and leverage.

Edward thinks that anything that creates an illusion of wealth is a bubble.

- Just because the last two bubbles (dot.com and US real estate) were about assets, doesn’t mean that you can’t have a bubble based around liabilities.

And since the pensions promised to US workers probably won’t be paid in full, they are a bubble.

Today’s cost of a pension (the “present value”) is calculated by discounting the actual promised cash flows in the future by an interest rate.

- This rate is linked to bank base rates, and as they have fallen over the past decade, the cost of pensions has increased.

So lots of pension schemes now don’t have enough assets to pay out the future claims – they are in deficit.

- The total deficit for US corporate pension plans is now around $425bn.

- US public sector pensions are in the hole for somewhere between $1 trn and $3 trn.

But in fact it’s worse than this. US pensions assume an annual return of 7.1%, which will not be achieved in the future.

- Half that rate would be an achievement.

US public sector pensions also discount liabilities at 7.5%, and even corporate pensions discount at more than 4%.

- Yet bond yields are less than 2%.

Several US towns have already declared bankruptcy and more will follow.

- The insurance scheme for corporate pensions (The Pension Benefits Guarantee Corporation) is 50% underfunded and is likely to go bust in a few years.

The effect on future corporate investment of diverting cashflow to plug pension deficits is a serious problem.

- But government pensions debts (for the 20 OECD countries) are estimated at $78 trn, twice the reported figure for national debts.

Which is why Edward is calling it a bubble.

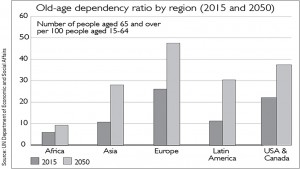

Demographics

Also in MoneyWeek, Jonathan Compton looked at the demographic trends that will change the shape of the world over the next 35 years.

A key component in the health of an economy is the ratio of working age people to those retired (Jonathan calls this the “grad-to-granny” ratio).

- As we all know, birth rates have dropped and people are living longer.

- So the demographic winds are blowing in the wrong direction. But what will it all mean?

The growth rate actually peaked in the 1960s, when the world’s population grew by 22%.

- We’re down to “only” 8% per decade now, and probably only 0.5% by 2050.

- Apart from an unexplained decline in male fertility, this is mostly down to urbanisation and increased female education and participation in the workforce.

So global population should peak at 9 billion (its more than seven at the moment).

- But will the damage have already been done by then?

The number usually used to measure the workforce is the dependency ratio.

- “Grad to granny” compares 20-29 year olds with 50-75 year olds

- The dependency ratio measures 15-64 year olds against those over 65

In the UK today, there are 42 dependants per 100 workers.

- In America it’s 49, Germany 52, and Japan 57.

- By 2050, these ratios grow to 70 in the UK, 66 in America, 83 in Germany and 96 in Japan.

Traditional government finance works on the principle of an ever-growing population, leading to more workers, and more tax to finance an ever-growing national debt.

- As the dependency ratio increases, taxes fall and the demand for state benefits rises.

Jonathan expects bond markets to start to price in demographics, as some countries are likely to go bust.

- We can already see the effect on rising state retirement ages, and this trend will only accelerate.

The second problem is drawdown.

- Workers consume, the retired drawdown their accumulated savings, or worse still they hoard their money.

- They also create low-paid low-productivity care jobs that further decelerate the economy.

And they also change their investment mix:

- US data shows that equity exposure peaks at age 45, at around 80%

- by age 75, bonds are up from 10% to 30% of a portfolio

- even worse, cash rises from 5% at 45 to 50% at 75

The outlook for equities is therefore negative, and the modest increase in bond exposure might not keep up with the government debt.

Other likely changes include:

- encouraging immigration (the UK’s solution for the past decade, and now Germany’s)

- compulsory savings (we have only reached the “opt-out” stage here in the UK, but compulsion must be around the corner)

- returning the retirement age to just around the time that people get sick, as was the case a century ago

Jonathan had some ideas on where to put your money to defend yourself:

- pharmaceuticals, especially treatments for Alzheimer’s and cancers (the suggestions were mostly US biotech stocks, but he included Smith and Nephew – LON:SN)

- automation (he tipped a Japanese stock here)

Until next time.