Weekly Roundup, 19th December 2017

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup in the FT, where Tim Harford was looking at how to have a Happy Christmas.

Contents

Happy Christmas

Tim has written before about the deadweight loss of Christmas – that recipients of gifts always value them at less than the giver spent on them – but this year he provided a more general economist’s guide to a happy Christmas.

- It’s actually as much a psychologist’s guide as an economist’s.

He draws parallels with stock market theories and practices.

- First up is the “efficient presents hypothesis”, which is that the most suitable gifts will already have been bought by the recipients themselves.

- Next is passive gift-giving – cash is dull but difficult to beat (because of the deadweight loss mentioned above).

- Since cash is often socially unacceptable, next best is getting recipients to declare wish-lists (or you could just ask them what they want).

- Recipients still think the gift is thoughtful, since you bothered to find out what they want.

- Third up is adding your time and attention as a supplementary gift, using the time that you’ve saved by simplifying the gifting process.

Merry Xmas, everyone.

Avoiding Stalin’s bullet

Also in the FT, John Authers wrote about the strategy that Jeremy Grantham – founder of GMO – would use to avoid Stalin’s bullet.

- The concept here is that Stalin has asked Jeremy to provide real returns of 4% pa for the next 10 years.

- Failure would be met with a bullet, as was common in Stalin’s Russia – another reminder for any readers planning to vote for a communist government in the UK next time around.

The interesting part of this thought experiment is that it gets rid of the career risk that makes so many fund managers so conservative.

- Jeremy will not be judged for falling behind his peers over 3 months, a year, or even five years.

Of course, as DIY investors we don’t really suffer from career risk.

- But it’s still very easy to be influenced by the stocks that other people (bloggers, say) are buying, and to accept the consensus view on markets and economies.

Back to Stalin’s bullet.

- Everything looks expensive – a 60 / 40 equities / bonds portfolio looks doomed to fail.

Asset allocation is key here, with stock selection less of an influence (as well as being less reliable).

- But you need to allocate before the herd – before the clear trend is in place.

So Jeremy went for a big bet on emerging markets.

- He expects the next year to be rocky, but the 10-year view is rosy.

The corollary is that the US market is one to move away from.

Bitcoin

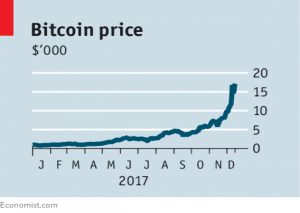

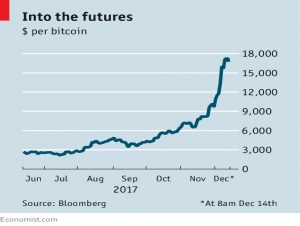

The Economist returned to the subject of Bitcoin with two articles (1 and 2).

Before we look at them, I should point out that I no can no longer open long spread bets on crypto with IG, as I mentioned a couple of weeks ago.

- Since I think that the coins will go higher before they inevitably crash, I will have to investigate alternate ways of gaining exposure (another spread bet account, or the ETNs that Hargreaves Lansdown is offering).

The Economist noted that trading in bitcoin futures began this week in Chicago.

The problem is there is no real way to value them, because there are no underlying cashflows (as with bonds and equities).

- There is a marginal cost of production (as with a commodity) but it is so far below the current value of a coin as to be useless.

The touted limited supply is not a sufficient condition to impart value, and in any case, many alternative coins exist.

Nor can the suggested replacement of fiat currency by crypto be taken seriously in the short term:

- BTC is not a good store of value (it’s too volatile), nor medium of exchange, nor unit of account.

- And there is no sign of the hyperinflation that might damage “real” money.

BTC’s best hope of long-term success is for its underlying ledger to be adopted for some widely-used service or services.

- Its anti-authoritarian and semi-illegal origins militate against this.

The good news is that since BTC is even now worth less than half of Apple, it is unlikely to trigger the next financial collapse.

The FT also had an article about Bitcoin, written by Hannah Murphy.

- It’s a decent read, though it covers increasingly familiar ground.

Passion investments

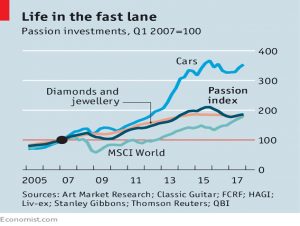

Sticking with the fringes of investment, The Economist reported that the passion index (which tracks the things I usually call SWAG – stamps, coins, art, gold, jewellry and cars etc.) has been keeping up with the MSCI world index.

- Since 2007 its up 5.9% pa, slightly better than the stock index.

Though the returns are typically unstable, they are not well correlated to stocks, so they can be useful.

- The real problems are illiquidity, lack of fungibility and extraordinarily high trading, storage and insurance costs.

Stay away, unless you are rich enough not to care.

Buy-to-let

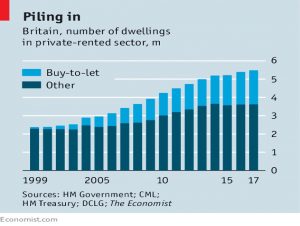

The Economist also wrote about the end of the buy-to-let boom.

- One in 30 adults (and 25% of MPs) are BTL landlords, of whom one-third are retired.

The Economist estimates total annual rents at £60 bn pa.

- Not bad for a market that began in 1996, when the first investment mortgages were introduced.

This was good timing, as house prices in the UK have since boomed.

- Even if they hadn’t, the gearing effect of a mortgage juices up the usually mediocre returns from property, making it appear a better investment than the alternatives.

- On a risk-adjusted basis it is not.

And, of course, nothing lasts forever:

- Rising capital values mean lower yields (the average is now below 5% pa), and a higher risk that prices will fall in the future.

- And of course we are at the bottom of the interest rate cycle, so mortgage payments are likely to increase from here.

While a rental market is a good thing on paper (it supports labour flexibility and hence productivity), the riches to be made from property incite envy from those too poor and / or too young to play the game.

- This in turn leads to government action, in the form of adverse changes to the tax rules.

Stamp duty on second homes has been raised already.

- Soon mortgage interest relief will be restricted to a 20% post-tax allowance, disproportionately increasing the tax paid by BTL landlords.

- And indexation of capital gains for those who hold their properties in a company has just been removed.

The BTL good times appear to be behind us.

- The most likely development is a shift from amateur landlords with a few properties, to institutional ones (pension funds and insurance companies) with thousands.

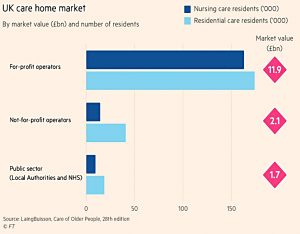

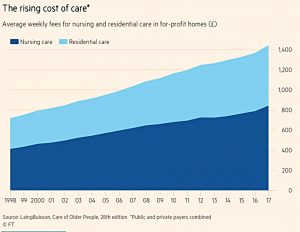

Care homes

From one corner of the property market to another.

- Our fifth article from The Economist looked at the state of UK care homes.

Back in the 1970s, councils funded and provided the care.

- Now they fund only those will less than £23K in assets.

- Richer old folk must pay their own way.

Most homes are now in private hands in a fragmented sector.

- As council budgets have been cut, profitability has fallen, since the councils are monopoly buyers for the 50% of spending on poor clients.

This has led to a lack of investment in the increased care home capacity needed for the future.

- The number of beds available has fallen slightly over the last couple of years.

This in turn leads to greater pressure on hospital beds from people who are well enough to leave but have nowhere to go to.

The Dilnot report in 2011 suggested that because residents don’t know how long they will live for, they choose the cheapest care available so that their money will last longer.

- This limits the profitability of the homes.

A second factor has been the recent increases to the minimum wage.

- And a loss of foreign workers after Brexit will probably make things worse.

Dilnot’s solution to the first problem was to cap payments at £35K per person (£40K in 2017 prices).

- Cameron increased the cap to £70K and delayed its implementation to 2020.

Then in the turning point of this year’s general election, Theresa May proposed raising the asset cap to £100K, but including the family home in the calculation.

- Paying for care received in the home – rather than at a home – would also have been introduced.

This was dubbed the dementia tax (since cancer care is free, but care for dementia would not be)

- It handed the momentum to Corbyn and Momentum, and was quietly dropped after May scraped through the election.

So there are no solutions on the horizon at present.

The FT also had an article on care homes from Gill Plimmer.

- This one focused on the debt burdens and complex corporate structures of their private sector owners.

The current attention on the sector stems from the likely takeover of struggling operator Four Seasons by the hedge fund that owns most of its debt.

The ownership question is a difficult one.

- If there was a state monopoly on the payments (rather than 50% being from individuals) then state ownership of the homes might make sense.

The alternative would be to fund social care via private insurance, which would make private ownership of the homes not an issue.

- But the current half-way house suits nobody.

Scrapping inheritance tax

In the Times, Ed Conway of Sky wrote about how scrapping inheritance tax would be good for all of us.

- The commonly held view is that rich people pass money to other rich people, increasing inequality, but that is wrong.

A new study looking at data in Sweden has found that inheritance reduced the Gini coefficient of inequality by 6% (a similar impact to a large stock market crash).

- The mechanism is that most people have more than one descendant, and so wealth is diluted over time.

- And a smallish inheritance can make a big difference to the standing of a poorer household.

Of course, a similar effect could be achieved by redistributing the takings from inheritance tax to poorer families.

- That’s what governments aim to do, but making the purpose explicit would make the least popular of all taxes even more reviled.

For me, the simplest solution is to replace IHT with a gifting system that forms part of income tax – the recipient pays the tax, and the donor is free to give to who he wishes.

Twitter pics

I have four for you this week.

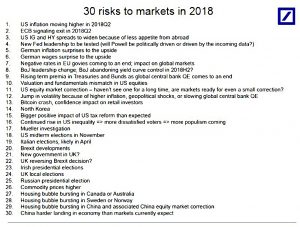

The first is a list rather than a chart – a list of thirty risks to markets in 2018.

- It’s an interesting read, if a little bit from a US perspective.

- My two key worries (Brexit and a Corbyn government) are both on there (indeed, Brexit appears twice).

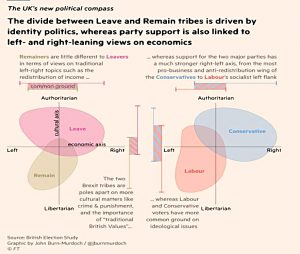

The second one shows that while Labour and Conservative exist along the traditional left-right political spectrum, Remainers and Leavers have more in common politically, but disagree along a cultural dimension (crime and “British values”).

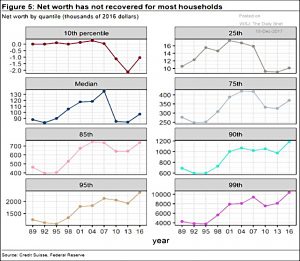

The third shows that only the highest wealth percentiles (in the US) are now better off than the financial crisis.

- Their recovery has been asset-driven, and the poorer percentiles don’t have much in the way of assets.

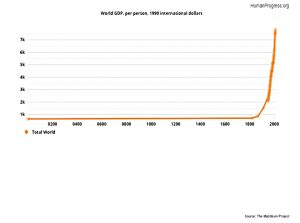

The final chart is more cheerful, showing the extraordinary increase in GDP per person provided by capitalism over the past two hundred years.

Until next time.

I’m a bit of a bore on the subject, but I scream inwardly at the phrase “dementia tax” and even more when journalists state that ” cancer care is free”. Medical treatment is free but personal care us not. That applies equally to both cancer and dementia sufferers and indeed strioke victims of anyone else. Cancer patients pay for their social/personal care too until they have a very short life expectancy usually estimated 6 weeks. Unfortunately there is little active medical treatment for dementia patients but they need a lot of personal care of you include supervision and prompting. Dementia sufferers can also get this funding known as chc fasttrack but it’s harder to predict death from dementia so it’s not often awarded. Some might think it is splitting hairs but it is quite wrong to cause division and envy between people suffering from nasty terminal conditions imho from lack of attention to detail. Mind you even The Guardian gets it wrong.

Hi Yvonne,

That’s quite an emotional reply. I apologise if I’ve hit a nerve. Do you think that the treatment of cancer and dementia patients is equal? Do you think that it should be?

The NHS is not a fair system. It favours people with trivial problems who want to see a doctor. It’s not the great medical institution that people in the UK believe it to be. We have lots of bad outcomes (eg. cancer).

If you want to socialise an area of life (which I don’t), then shouldn’t you do it properly?

Mike