Weekly Roundup, 12th December 2017

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup in the FT, with the Chart That Tells A Story. This week it was about the decline of cash.

Contents

Cash payments

Ed Bowsher looked at the reduction in the number of cash payments each year.

- They’ve fallen from 85% of all payments down to 40% over the last 20 years, and the rate of decline is increasing.

This was down to credit cards at first, and then debit cards.

- More recently, online shopping and contactless payments have been the cause.

- Contactless is now 30% of all card payments, and mobile payments (like Apple Pay) are on the rise.

As the proportion of cash payments has fallen, their size has increased.

- The value of cash transactions has fallen from £261 bn to £241 bn over the last 12 years.

- And the amount of cash in circulation has doubled since 2005 – from £35 bn to £73 bn.

Ed wonders whether cash will ever die out.

- Central banks seem keen, as it makes it easier to implement negative interest rates.

- But people and shop seems to like it – it’s cheaper, more reliable and easier to budget with.

And it makes you spend less – handing over physical money is harder than spending electronic cash.

Anti-bubble

John Authers looked at the idea that the bitcoin mania means that there might be “anti-bubble” rewards somewhere.

- As he points out, there is currently a bubble in everything – stocks, bonds, art, even property here in the UK.

But if Bitcoin is a bet against asset price inflation elsewhere, why is it up 800% this year when gold is only up 10%?

- John puts it down to distrust of governments, which is widespread in Asia (and particularly ion China) and common amongst the young in the US.

He finds people’s faith in cryptography and unidentified developers “horrifying”.

- As for the anti-bubbles, gold is the best that he can come up with.

Review of 2017

Merryn had an early review of 2017, which she described as a year of consequences.

QE and low interest rates have made asset prices soar and increased inequality.

- Zombie companies have been left alive, and governments have coped with their enormous debts.

- Pension schemes have actuarial deficits, diverting funds from productive investment.

And the results have been Brexit and the rise of Corbyn.

- Which in turn has lead to investors withdrawing money from UK assets.

This is despite the UK market trading on its largest discount (to book and sales) for 20 years.

But this cheap valuation hides a bifurcation:

- More FTSE-350 stocks trade on PEs over 20 than ever before.

- And more than normal trade on PEs of less than 10.

Even though the gap between sectors is lower than normal.

- The differentiator appears to be foreign earnings, which are highly valued.

Merryn notes that Neil Woodford’s reaction has been to buy more cheap domestic cyclicals.

- Merryn agrees with this, but recommends Diverse Income Trust, Aberforth Smaller Companies, Temple Bar and Miton Microcap fund rather than Woodford’s fund.

She also recommends multi-asset funds like Troy Trojan, especially over the illusory “safety” of bond funds.

At the moment I expect Corbyn to win an election, and the UK economy to suffer greatly.

- So I’m gradually moving UK assets into cash, in anticipation of buying them back more cheaply in a year or three.

Capital controls

Stocking with Corbyn, Simon Wilson in MoneyWeek looked at the likely return of capital controls.

- In order to counter capital flight in the event of a Labour government, the party has discussed not only exchange controls but also restrictions on what kind of assets people can own.

It sounds far-fetched, but between 1914 and 1979, Britons could take no more that £50 abroad on holiday, and all transactions were recorded in passports.

- There was also a fixed pool of foreign assets that could be owned by Britons, and if you wanted to buy, someone else had to sell.

Like so much else that was wrong with the UK in the 1970s, this system was abolished by Thatcher’s government.

- The US, Canada, Germany and Switzerland had got rid of them from 1973.

Free capital is like free trade – it makes everybody richer, by moving money to where it would be most productive, and by keeping interest rates low.

- There is some evidence that temporary inflows can destabilise smaller and / or developing countries.

- But for large, rich economies like the UK, free capital does what it says on the tin.

Perhaps everybody being richer isn’t the aim of a Corbyn government.

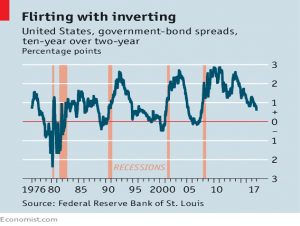

Yield Curve

The Economist looked at the flattening yield curve.

- The difference between ten-year and two-year rates in the US is the smallest it has been since before the 2008 financial crisis.

- And long-term rates have dipped below short-term ones just before each of the previous seven American recessions.

Long-term rates largely reflect investors expectations of inflation, via the “term premium” – the excess over short-term rates that they require for taking default risk for a longer period.

- When inflation is high, long-term holders have lower real returns, and miss out on the boost to short term rates that an inflation surprise leads to.

So a flat curve reflects low inflation ahead, and an inverted one can signal deflation.

- They also signal lower interest rates ahead, usually via recession-combating cuts.

Another factor today is foreign investors buying US bonds which yield more than their own local ones.

QE also seems to have reduced the term premium, and so its removal and eventual reversal might do the opposite.

- The implication is that it will be more difficult to raise rates than the Fed expects, and so rate rises might proceed more slowly than they would like.

But if the Fed is right, and inflation takes off, the reversal of investors’ bets could produce a rapid bond market crash.

Goldilocks

Buttonwood thinks that the markets believe in Goldilocks.

- They keep going up, despite the risks.

Purchasing managers around the world are optimistic, and the US tax cuts are expected to boost stocks further.

Almost half of fund managers (a record) think that stocks are overvalued.

- But 49% of them have higher weightings to stocks than normal.

- Because 81% of them think bonds are overvalued.

The Goldilocks scenario means higher than normal growth with lower than normal inflation, which is holding up at the moment.

- But further growth in corporate profits would mean even less for the workers, and a likely rise in populism.

Buttonwood notes that the massaging of reported earnings and share buy-backs (both higher when stocks are doing well, rather than the opposite, which is more logical) mean that any correction will be exaggerated lower reported earnings and an end to buy-backs.

- But when that will happen is anybody’s guess.

State Pension

The Guardian reported that the UK has the lowest state pension of any OECD country, just below Mexico.

- It averages 29% of previous earnings, compared to an OECD average of 63%.

In the Netherlands and Italy, the pension is more than 80% of previous earnings.

- And Turkey pays out an average of 102%.

- But in the UK, we rely on private pensions to bring us closer to the average.

The new state pension is higher than the one it replaces, and it will make a difference in the long term.

- So will workplace auto-enrolment.

But for the next 20 or 30 years, we’ll be at the bottom of the league table.

- Think about that the next time the media complains about the triple lock.

Sovereign Wealth Fund

There have been a few articles over the past couple of weeks about the UK setting up a Sovereign Wealth Fund (some people prefer to call it a National Investment Bank or Social Wealth Fund), so I thought that I would summarise the arguments.

- The idea is that rather than borrow to pay more welfare (the Corbyn plan), we issue bonds (say £100 bn to £200 bn) to fund housing and infrastructure, as well as venture capital and direct lending to business.

We should end up with productive assets financed at record low interest rates (negative after inflation), and a boosted economy.

- And over time the return on assets would exceed the interest paid out, and reduce the country’s debt.

It could also help to solve the country’s productivity problem (something I will return to in a future post).

- And it would replace funding from the European Investment Bank, which will be lost following Brexit.

More fanciful observers even see it providing a universal Basic Income over time.

It sounds like a capitalist version of Corbyn’s “People’s QE” and in a sense it is, but we don’t really know how that would play out.

- Corbyn wants a much bigger fund (£500 bn?) and might not match the additional liabilities in the government’s books against the assets the fund invests in.

It’s a nice idea in principle, and one I’ve always been keen on.

- Such a fund might also be used as a national investment fund for people to save into, or a default workplace pension fund.

But we should have done this in the 70s, using a levy on North Sea Oil, like the Norwegians did.

- Then maybe we’d be the richest country in the world.

In practice, this Tory government is too weak to implement such a plan, and under a Labour government, the likelihood of disaster is extremely high.

Twitter pics

I have four for you this week.

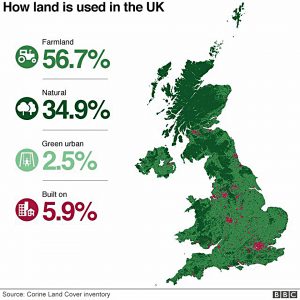

The first shows land use in the UK.

- There’s plenty of room to build new houses – but would they be where people want them?

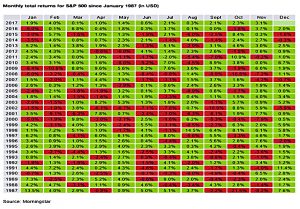

The next shows that 2017 could be the first year in the last 30 to have no down months at all for the S&P 500.

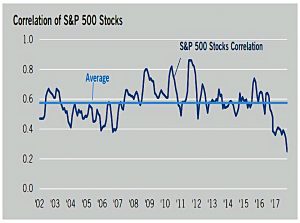

The third shows that correlations between S&P 500 stocks have broken down – not everything is moving up in lockstep.

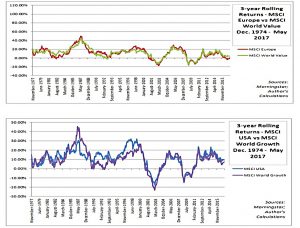

The final chart shows that Europe is a value environment, and the US is a growth environment.

Until next time.