Weekly Roundup, 27th April 2020

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup with a look at dividends.

Dividends

In MoneyWeek, Matthew Lynn said that the dividend bonanza had come to an end.

- A total of £28 bn in dividends have been scrapped, from more than half of the UK’s quoted companies.

And paying a dividend has now become socially unacceptable, especially if a company has also furloughed staff or closed premises.

The last 20 years (particularly in the US) have been a bonanza for shareholder payouts (buybacks and dividends combined) but now that looks to be at an end.

- The level of investment was low because it was relatively unattractive, and required less capital than previously, thanks to technological advances.

And there was a lot of pressure from the market (and from management teams incentivised with share options) to focus on shareholder value.

Looking forward, supply chains will need to be made more resilient, and production will become more local.

- And state aid will be tied to cutting shareholder payouts.

So dividends won’t be restored quickly, or in full.

In the FT, John Lee was unhappy with the dividend cuts.

It may well be that the cult of the dividend was overdone, that some PLCs paid out more than was commercially sensible. However, the arrival of Covid-19 [means that] the majority of quoted companies will suspend or defer payments, with 2020 turning into a very thin year.

John was happy with cuts from Air Partner, Appreciate and Vitec, which are in sectors bad;y-affected by the virus.

- But he was concerned by a change in attitudes:

Paying dividends at the present time is somehow antisocial and immoral.

Banks have been told not to pay a dividend, but insurers were simply warned to be prudent.

- Legal & General plans to pay, but Avivia has pulled its dividend, which earns “a big raspberry” from John.

Even worse, there were no pay cuts for the execs (though bonuses were suspended).

I talked previously of “parking” earlier takeover proceeds in Aviva on a 7.5 per cent yield. It turned out to be the most expensive parking ticket in history! I waved goodbye to Aviva and topped up my holding in L&G.

John was even angrier with Nichols:

The Vimto maker acknowledged it has £40m in the bank and no debt — four times the cost of the dividend.

Sticking with dividends, Imogen Tew reported in FT Adviser that the Investment Association has scrapped the yield requirements for funds within its UK and Global Equity Income sectors.

- Normally, such funds have to beat the FTSE All-Share yield on a three-year basis and have at least 90% of the FTSE All-Share yield on a 1-year basis.

In other words, dividends are toast, and buying an income fund doesn’t mean you are investing in income-producing assets.

- Shades of the Woodford scenario.

Regular readers will know that I am no fan of dividends.

- Dividends don’t come out of thin air – it’s shareholders’ money being paid back to them in a tax-inefficient manner.

- Compounding is real, but the idea that it requires dividend reinvestment in the same company that produced the cash is nonsense.

I think that the dividend drought will continue for a lot longer than dividend fans expect.

- Dividend investing will join value investing in the pile of popular strategies that “work sometimes”.

Use more than one investing approach, and work out when to switch between them.

Fundraisings

Merryn Somerset Webb was concerned that small investors are being excluded from emergency equity fundraisings.

Listed companies have long been allowed to issue new shares to the tune of 5% of their outstanding share capital every year without jumping through many time-consuming admin hoops. The Covid-19 nightmare has led to these rules being relaxed [to] 20%.

But an issue dilutes existing investors who don’t participate.

- And it usually needs to be made at a discount so that people want to invest.

So ideally the offer should be made to everyone.

Since early March, some £2.7bn has been raised by firms under the new regime. Most have excluded retail investors. Getting to the thousands of ordinary individuals out there is considered too hard.

Merryn says that with new technology, it needn’t be.

- A similar argument can be made for individual share register accounts, rather than the current use of nominees.

She mentions Primary Bid, the phone app which sends push notifications of new raises.

The investment platforms are keen — most of their bosses signed an open letter this week, supported by Primary Bid, to the boards of UK-listed companies complaining about retail investor exclusion.

Platforms would obviously make money from such raises, but that doesn’t make wider participation a bad idea.

Another leg down

Back in MoneyWeek, Mark Mobius warned of another leg down in stock markets.

Human behaviour tends to follow predictable patterns because of human nature. We have studied 11 stock markets and their bear markets since the end of the 1980s.

Here are Mark’s findings:

- The average bear market decline was 49% but falls ranged from 23% to 92%.

- A bear market lasted on average 15 months but the range was from a few months to five years.

- Emerging markets were more volatile, with an average decline of 50% over one year.

Since the FTSE All-Share is down only 25% and the max drawdown so far has been around 36%, we could have further to go.

- I think the Q2 reporting season in the US (starting in July) could trigger another down leg.

Future fund

Anthony Rose of SeedLegals explained that the government’s Future Fund won’t help UK startups.

He had three main points:

- The £250M pot is too small

- It would need to be 20 times bigger to offer support to all of the startups that need it

- It’s not compatible with EIS/SEIS, which drives the vast majority of early-stage UK funding

- Taking advantage of the Future Fund would bar a company for using EIS/SEIS in the future

- And since VCs like to see revenue, this effectively excludes pre-revenue firms

- Deal terms (which are non-negotiable) offer a 2X pay-out to investors (but not to the government)

- Anthony is obviously on the side of the entrepreneur, but I think in these tough times, a bias towards investors might be permitted.

Here’s his table of deal terms:

Other scheme points include:

- The company needs to have raised at least £250K already

- You need matched funding from other investors (at least £125K) before you can get any money from the government

- Existing convertible notes aren’t compatible with the scheme

- £250K is the minimum you can take from the fund

Anthony’s conclusion is:

It looks like a bunch of VC lawyers got together to try to come up with the best deal terms that an aggressive investor would squeeze out of a distressed company that had nowhere else to go.

Most startups would be better off ignoring the scheme and focussing on finding SEIS/EIS angel investors.

Hard choices

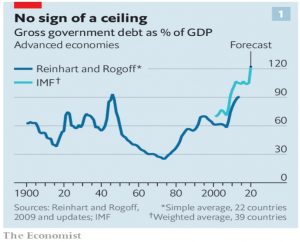

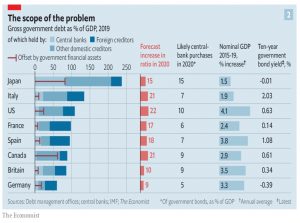

The Economist warned that developed countries face hard choices on how to pay down the debt generated from the pandemic.

- The average deficit will be at least 11% of GDP, and the average debt at year-end will be around 122%.

The three repayment options are:

- More tax (and less spending)

- Default (full or partial) or extension

- Grow the economy (through inflation and/or productivity) in order to shrink the debt over time

There seems at the moment to be little appetite for a repeat of the “austerity” after the 2008 crisis.

- This time is not as easy to argue that we have all spent too much and need to tighten our belts.

Defaults are common amongst EMs, but not so likely in developed nations.

- Cuts to future government spending on health and pensions act in a similar fashion, though once again, it’s hard to see the popular appetite at the moment.

So option three is most likely.

The secret to this is ensuring that the economy’s combined level of real economic growth and inflation stays handily above the interest rate the government pays on its debt. That allows the debt-to-gdp ratio to shrink over time.

And we all managed to do this after WW2:

America’s public debt was 112% of GDP, Britain’s 259%. By 1980 America’s debt-to-GDP ratio had fallen to 26% and Britain’s to 43%.

This involved tolerating high inflation and the use of “financial repression” – interest rates lower than they ought to be.

To attempt such repression today, though, would require redeploying tools used by post-war governments – capital controls, fixed exchange rates, rationed bank lending and caps on interest rates.

We could also see wealth taxes, higher taxes on land and inheritance, and new taxes on carbon emissions.

- You have been warned.

Quick links

I have eleven for you this week, the first seven from the Economist:

- The newspaper explained that the euro is more durable than it looks

- And that oil markets have a timing problem

- And that Netflix will remain a hit during Covid-19

- And that UK fast-food chains are slowly reopening

- And in the first of three articles about the car industry, that lithium is still the car-battery material of choice

- The second article said that giant car firms need to move fast and break things

- And the third painted a gloomy picture – short-term crisis and long-term decline

- Alpha Architect said that trend following is everywhere

- Musings on Markets looked at the effect of the virus on multiples

- Mauldin Economics had some viral thoughts

- And Flirting with Models looked at Tranching, Trend, and Mean Reversion.

Until next time.