Weekly Roundup, 19th July 2016

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup in the FT, with the Chart That Tells A Story. This week it was about entrepreneurship, particularly in the over-50s.

Contents

Over-50s go it alone

Sarah O’Connor took a look at some new data from the ONS.

- Self-employment in the UK is up from 3.8M in 2008 to 4.6M in 2015, and from 13% to 14.6% of all jobs.

- Builder, carpenters and taxi-drivers are the most common professions, but most of the recent growth is in finance and business services, and concentrated in London and the South East.

But more than 40% of the self-employed are over 50, compared to only 30% of employees.

- And part-time self-employment grew by 88% between 2001 and 2015, compared to only 25% growth for full-time self-employment.

The ONS concludes that older workers are choosing a more gradual path towards retirement.

It’s possible that self-employment is through necessity, but the ONS survey now includes a section on why people are self-employed, and few seem to be unhappy or to want a full-time position.

- Younger men on the other hand – though not women – are unhappy with their self-employed status.

- Unions claim this reflects “bogus” self-employment for people like delivery drivers, where their employer is aiming to avoid extra NI and pension payments.

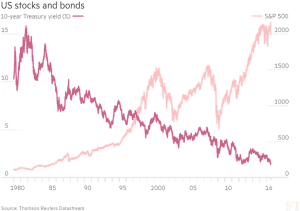

Bonds and stocks

John Authers looked at the strange circumstances between record stock prices (in the US) and record low bond yields (ie. record bond prices).

- These two assets are supposed to move mostly in opposite directions, but not during periods of record low-interest rates.

Low bond yields should mean that investors fear a recession, and are shunning riskier stocks.

- But the recent US jobs report (Non-Farm Payrolls, or NFP) was very strong, suggesting no recession and possibly higher US interest rates (bad for bonds) in the future.

The new high in stocks, the first for 14 months, is also bullish for stocks.

- But within the market, the best performing sectors over that period have been minimum volatility stocks and high-yielding “bond substitutes” – both of these should do well in a recession (though telecoms, real estate and utility stocks all now look expensive as a consequence).

S&P500 earnings fell by 5% year on year in 1Q2016, and the forecast is for another 5% fall in the second quarter.

- Normally stocks in aggregate beat their forecasts, so a slight relative improvement is expected in Q2.

But this is not enough to explain the rally.

As John points out, it has been a stock picker’s market recently (lots of 20%+ gains, lots of 20%+ falls).

- Yet the stock pickers (eg. equity hedge funds) have not done well.

John comes up with two reasons for the stocks rally:

- the rapid resolution of the next PM question in the UK, in a way the market likes

- the expectation of further central bank stimulus in the UK, Europe and Japan – and possibly even in the US.

That doesn’t make working out where to invest any simpler.

Bond funds

In the light of the recent suspensions of open-ended real estate funds, Paul Killik in the FT looked at fund liquidity more generally.

- He’s particularly concerned about bond funds.

In principle, bond funds are liquid, since the underlying bonds are traded.

- But there are lots of differences between bond funds and bonds that investors may not recognise

The key attributes of a bond are the credit risk, the coupon and the redemption date.

- Bond funds have none of these, or rather they substitute averages for specifics.

The problem is that retail investors are excluded from trading most bonds directly (they have minimum lot sizes of £50K or £100K and extra prospectus requirements on primary issuance) so bond funds and ETFs are the only game in town for them.

So we have lots of retail investors in funds invested in a bond market near the end of a 20 to 30 year bull run.

- Unlike holders of individual bonds, who would most likely hold on for their redemption date, investors in bond funds may well try to exit the asset class when the bond market finally crashes.

Regulation since the 2008 financial crisis means that it’s less advantageous for banks to hold bonds, and so liquidity has gradually been removed from the market.

- So prices could fall very sharply in the face of retail selling – with no other natural buyers of bond funds, they will need to be cheap before they find institutional support.

- And retail investors won’t be able to access the now cheap individual bonds to offset their losses.

Bond funds may be forced into the gating we’ve just seen from real-estate funds.

- And this gating could conceivably last for years, until bonds mature.

Paul finds it ironic (as do I) that this looming problem for private investors stems from regulations designed to protect them.

Alternative finance

The second product warning of the week comes from Aime Williams in the FT, who was reporting on the launch of an FCA review into P2P lending and equity crowdfunding, together known as “alternative finance“.

- The review has been planned since 2014 and most providers have welcomed it.

P2P lending has grown much more quickly than crowdfunding, and has attracted more institutional capital (largely through a series of investment trusts).

- P2P raised £911M in 1Q2016, compared to only £33M of crowdfunding.

This is generally thought to be down to the lower-risk reputation of P2P (though lower risk is no low-risk, and certainly not no-risk).

- As well as the basic higher risk of equity compared to debt, crowdfunding platforms often obscure the sources of all funding, leading the public to believe there is more third-party interest in an issue than is the case.

There’s no detail on when the FCA will report back.

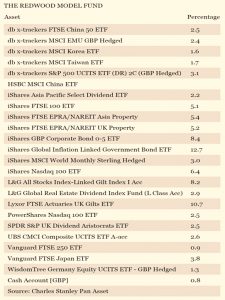

Redwood fund – Brexit bargains

John Redwood provided his regular update on the paper ETF portfolio he manages for the FT.

- The focus this time was Brexit.

John expected a Leave vote, so he positioned the fund for a mark down in equities and an upturn in bonds.

- When this indeed happened he started to unwind the positions but the speed of the post-vote recovery meant that he got only half of the reversal away, switching 5% of the fund from bonds to the FTSE-100.

- As it happened, both bonds and the FTSE-100 continued to rise, so the portfolio has done well (up 7% in 2016).

As a Leave voter, John is not worried about Brexit.

- He expects the EU not to impose tariffs that would hurt its own exporters, and for the savings from EU membership to be used to fund business tax cuts.

- He expects foreign demand – driven by sterling weakness – to underpin UK property.

Here are the current constituents of the portfolio:

Wishful thinking

Tim Harford’s column was about wishful thinking, which he managed to tie back to Brexit.

He talked about research by Guy Mayraz at Oxford using predictions of wheat prices.

- Participants were shown historical price data and asked to predict the next day’s price.

- The twist is that some were told they were farmers (who would profit from higher prices) and some were told they were bakers (who would make more money from wheat being cheap).

- As you might expect, farmers predicted higher than average prices, and bakers predicted lower than average prices.

Tim says that Remain supporters appear to have similarly predicted that their dreams would come true.

- Even during the mid-June run where nine out of ten polls gave Leave the lead, the betting markets never gave Leave better than a 40% chance.

Wishful thinking is linked to confirmation bias, where we cherry-pick the facts to support what we believe (or predict).

- Remain voters now see evidence of a looming catastrophe, whereas Leave voters see opportunities everywhere.

- Evidence like lower high-street footfall, fewer job adverts and the property-fund freezes are either real indicators of damage, or simply reflective of the gloomy mood amongst Remainers.

Tim, as a Remainer, says that the initial collapse of the pound and FTSE-100 made him feel that he was right, but the subsequent recover in stocks didn’t reassure him at all.

Tim’s conclusion is that we should spend less time predicting a specific future, and more time stress-testing ourselves against a range of possible future scenarios.

This may have something to do with the time he spent in Shell’s scenario planning department.

- But it’s a good idea none the less.

The right question is not “What will happen?” but rather “What will we do if this happens?”

Brexit impact

The Economist was looking for signs of the economic impact of Brexit.

- In the markets, the signs are clear – the pound has fallen by 10% against the dollar, and the uk -focused FTSE-250 is down, even if the globally-focussed FTSE-100 is substantially up.

There have no official statistics on the real economy since the vote, so the Economist has “scraped” unofficial numbers from the web.

- Consumer spending is holding up okay (OpenTable bookings, John Lewis weekly sales, retail Footfall, mySupermarket figures on Tesco discounting).

- But corporate investment is being delayed (Adzuna job listings, Google searches for “jobseekers” [allowance], P2P loans on Funding Circle, planning applications).

- The housing market may also be slowing (Zoopla price cuts, Chartered Surveyors inquiries).

And there may be an export boom beginning (flight bookings to Britain have risen), though the new competitiveness from the weak pound is offset by the more expensive imported components used in the things we export.

- In addition, countries like Britain tend to compete on “non-price” factors (quality and customer service) that aren’t affected by the weak pound.

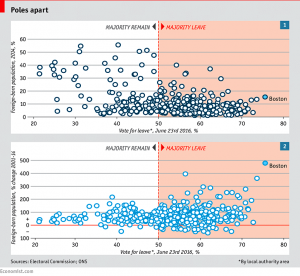

Who voted for Brexit?

On the same page, the Economist had a subtle revision to the argument that areas with lots of immigrants would like to Leave.

- It wasn’t the total level of immigrants that was a factor, it was the rate of change between 2001 and 2014.

- Of areas where the number of immigrants tripled in this period, 94% voted to Leave.

Negative rates

Buttonwood looked at the effects of low and negative interest rates on the financial system.

The first problem is banks.

- Banks take deposits and loan them out at higher rates and over longer periods to borrowers.

- The smaller the gap between short-term rates and long-term rates (the flatter the yield curve), the harder it is for banks to make money.

With short-term rates near zero, they can’t even make money from “free” current accounts.

- And if the central banks makes rates on commercial deposits negative (as in Europe and Japan), these costs can’t be passed on to depositors.

A second factor is the ever-decreasing yield on the portfolios of bond that bank regulators require banks to hold (ironically, given the state of bond markets, for liquidity).

- So bank profits are shrinking, and they must either cut costs or increase the cost of corporate borrowing (the opposite of what central banks want them to do).

Insurance companies (which take premiums upfront, and invest them, increasingly in bonds) have the same problem.

- Lots of European insurers are stuck with savings products they sold at much higher yields than today.

And even those insurers with fund management arms are finding that low returns means that clients are now much more aware of the often high charges they levy.

- New business (especially from millennials) is going to low-cost trackers and ETFs.

In yet another of today’s ironies, low rates were introduced to save the financial sector, but are slowly suffocating it.

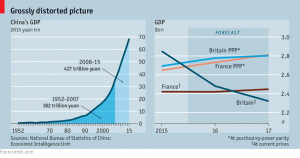

Comparing GDP

The Economist also had a couple of articles about the way that GDP is measured.

- We’ve written several times before about the limitations of GDP as a number, but here are some practical examples.

The first article asked whether Frances’s 26.4M workers were now producing more than Britain’s 31.1M employees.

- After the Brexit-driven fall in sterling against the euro, the UK’s £1.86trn economy would appear to be smaller than France’s €2.1trn.

But not everyone calculates GDP in the same way.

- China and India made big changes recently, albeit to bring them closer to international standards.

- China has revised its figures all the way back to 1952, to tell a dramatic growth story (see diagram).

Ireland made dramatic revisions only this week (more on this below).

And applying exchange rate fluctuations to a flow of goods and services (which is what GDP is) is different to revaluing a single asset, or a pile of assets.

- GDP is more like the wages and interest that a person earns during the year, rather than the figure in his bank account at the end of it.

- Which means that it must be measured over a period of time, rather that at a single point.

- The year on year change is the most significant measure, not the value at the end of the year.

And this in turn means that the exchange rates which prevailed during the year are the fairest ones to use when valuing, rather than the exchange rate at the end (ie. now).

- Many of the things that make up GDP (meals, travel, heating or a night out) no longer exist to be revalued at the end of the period.

Assets do matter in one sense – the popular UK assets (mostly gilts and London houses) bid up the price of UK currency needed to buy them, making Britain 16% more expensive than France during 2015.

The Economist settles for using purchasing power parity (PPP) exchange rates.

- Under this system, France almost caught up with the UK in 2015, but not quite.

- As for 2016 we will have to wait and see.

The second article reported on Ireland’s claimed 26% GDP growth for 2015.

- This was revised up from 7.8% because of the way that investments are now treated.

In particular, when a foreign (usually US) company carries out a tax inversion by re-registering in Ireland to take advantage of its low corporate tax rate, its assets (including intellectual property) are added to Ireland’s capital and these returns are included in GDP.

- Ireland’s capital stock grew by fully one-third in 2015, as US firms rushed to beat an expected crackdown.

Ireland also has a large aircraft leasing industry, and these planes (usually not located in Ireland) are now included in Ireland’s figures.

The massive increase in GDP sounds like a good thing, but it will make it easy for Ireland to keep its budget deficit below 3% of GDP.

- Which in turn means that the government could spend more or cut taxes, despite (or prehaps because of) the potential impact from Brexit.

There’s also the risk that no-one will trust the figures.

- As with the UK, growth is mostly concentrated in the capital, and those outside are not convinced it exists in any case.

- Changing the way the numbers are counted will only make matter worse.

Until next time.