Weekly Roundup, 3rd November 2015

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup in the FT, where Maike Currie from Fidelity was picking a fight with Warren Buffett.

Contents

Dividends

Buffett doesn’t like dividends, preferring to reinvest profits back into a business. Berkshire Hathaway has only once paid a dividend (in 1967) and Buffett jokes that he must have been in the bathroom when that was decided.

Maike thinks that a high dividend payout imposes capital discipline on a company and that it is often a sign of quality. She refers to a company classification system used by Carl Stick, manager of the Rathbone Income Fund.

- Compounders are high quality businesses with high returns and the ability to reinvest these to generate organic growth.

- Maike makes a distinction here with bond proxies – companies that pay an income that rarely grows.

- Examples of compounders are Reckitt Benckiser, Bunzl, Unilever and Howden Joinery.

- These companies typically have low business and financial risk, but come with a fair amount of price risk from a high valuation.

- The bond proxies go in the second bucket, called `cash cows’.

- These businesses generate high returns on a static capital case.

- Dividends probably won’t grow very quickly, because of their size (elephants don’t gallop) or regulatory / political pressures.

- Utilties, tobacco and telecom stocks fit here – mature and stable industries.

- Business and financial risk is still low but higher than for compounders as they are susceptible to disruptive change.

- They have more price risk than they used to as valuations have increased recently.

- The final bucket contains (quality) cyclicals, where sustainability of income is key.

- These companies make good earnings over an economic cycle and pay good dividends. Oil stocks and miners used to be the best examples. Pharmaceuticals are another example.

- If commodity prices rise in the next few years, then such companies look attractive.

- The key here is to work out where in the earnings cycle the company stand (in the drug life-cycle in the case of pharmas).

Maike recommends a mix of compounders, cash cows and quality cyclicals in a dividend portfolio. She also stresses the importance of dividend cover – a high yield on its own is not enough.

We covered Buffett’s position on dividends when we looked at his Annual Letter for 2012. Imagine a business with $2M net worth, shared 50/50 with Warren.

- The firm earns 12% pa on net worth and reinvested earnings, and outsiders will buy shares of at 125% of net worth. So each holding is worth $1.25M and generates $120K of earnings pa.

- If we pay out a third of earnings as dividends, the company is now growing at 8% pa (12% earned minus 4% paid out).

- After 10 years the company is paying each of us $86K in dividends and is worth a total of $4.32M.

- We each own shares worth $2.7M (at the 125% rating).

As an alternative, we could sell 3.2% of our shares in the market, which would produce $40K in the first year (at the 125% valuation), but would increase over time.

- What we still own of the company is still growing at 12% pa, rather than 8%.

- After 10 years the company is worth $6.21M. We each own 36.12% of the business – $2.24M.

- Our shares are worth $2.8M (at the 125% rating), around 4% more than the dividend approach produces.

- The annual cash receipts from selling 3.2% of our shares will now produce 4% more than the dividends.

For Buffett’s “sell-off” method to work in the long-run, you need the 12% annual earnings and 125% share valuation. Higher numbers work even better.

- Buffett also dislikes the “compulsory” nature of dividends. Those in the accumulation phase of investment should not want dividends (though it is simple – but not free – to reinvest alongside other contributions)

- There are also tax disadvantages in the US, but not in UK SIPPs and ISAs. ((And from next year, everyone receives a £5K tax-free band for dividends ))

For a committed long-term investor in quality companies like Buffett, his approach makes sense.

For the less skilled like myself, I prefer a hedged approach using a variety of strategies that are known to work. Then if one of the strategies suddenly fails, there are others to fall back on.

A dividend portfolio is just one of half-a-dozen or more approaches for me.

Crowdfunding minimum

Hugo Greenhalgh reported on industry demands for a minimum £1,000 investment into crowdfunding.

At the moment Joe Public can get involved in the £1.4bn crowdfunding industry for as little as a tenner (on which he will presumably make another fiver).

The calls reflect the split between companies with a venture capital or private equity background – who aren’t targeting the great unwashed – and those that have recently thrown up a shingle to squeeze as much out of them as is legally possible.

The latter are prone to exaggerate the potential of the businesses they are selling, whilst downplaying the ridiculous prices at which they are being sold.

It seems clear to me that either people don’t understand the level of risk that they are taking with equity crowdfunding, or that they regard it as a sexy version of the lottery – or as a charity donation.

The problem with the last two comparisons is the lack of good works of benefit to society as a whole. Crowdfunding is just easy money for entrepreneurs and platform owners, and a way to rope in “brand ambassadors” for free.

Of course what they say is “there’s a myth around whether the crowd is less sophisticated” and “why should investing remain the preserve of the wealthy”.

I’m not buying their PR bullshit, and I’m in favour of the minimum investment.

Stocks and central banks

John Authers looked again at the link between central banks and stock markets. Each changes in response to the actions – and the expected future actions – of the other.

Continuing low interest rates are good for stocks in the short run:

- they reduce the rate at which future earnings must be discounted, justifying higher PE multiples

- they make bonds less attractive, pushing investors into equities

Money also flows towards the best returns, so the ECB’s committment to more easy money in the future sends cash towards the US. Japan announces more easing just after John wrote his article.

China has stabilised since its crisis in August – partly because the Fed decided against raising rates – and emerging markets should follow suit. But China has cut rates and eased bank lending controls, sending more money out into the rest of the world.

Expectations of future rate rises have been pushed into 2016, and US stocks have risen. Even the Fed’s hint of a December rise has been shrugged off, partly through company earnings beating low targets.

John calls the situation over the past six years – a US economy strong enough to avoid recession but weak enough to need stimulus – the “Goldilocks on ice” scenario.

Now the betting is that it will continue, because of what is happening outside of the US.

Too soon for normal service

Over in the Economist, Buttonwood covered similar ground. He thought that world economies were still too weak for normal monetary policy to resume.

- Inflation remains low in Europe, North America and Asia.

- Sweden has just extended its QE programme, and the ECB is expected to announce more easing in December.

- As noted above, Japan announced more last week.

- Emerging markets are more mixed, but China and India are still easing.

The IMF just lowered its global growth forecast to 3.1% (not that low) for 2015.

- US profits are expected to be 4% down on 2014, with sales down 3%.

- European profits for 3Q2015 are expected to be down 5.4%, with revenues dropping 7.9%.

But Bloomberg’s commodity index is down by more than 25% in a year, and the ten-year Treasury bond yield is 2%. So a quick return to economic normality is not anticipated by investors.

All this adds up to what the newspaper calls an “awkward equilibrium”.

- Positive news will improve the profits outlook but make rate rises more likely.

- Bad news will prevent rate rises but bring its own problems.

Bonds have been stuck in a narrow trading range for a while, and now stocks looks to be in the same boat.

Low growth and low interest rates have made stocks relatively more attractive, but lack of profit growth means markets can’t rise too far.

Without a recession, they can’t fall too far either. What will break the deadlock?

The blockchain

The economist looked at the promise shown by the technology behind BitCoin (which we looked at earlier this year).

The currency itself has a bad reputation – unstable in value, ((It has actually settled around $250 this year )) and used to buy drugs and order hitmen from the “dark web”.

The underlying technology – the “blockchain” – is another matter. The newspaper calls it “a machine for creating trust”, and draws parallels with the dull but world-changing innovations such as double-entry book-keeping and the limited company.

There is also an analogy with Napster, the 1999 (illegal) peer-to-peer music-sharing service. Napster was shut down and was replaced by other illegal P2P services, but also let to legitimate P2P sites like Skype and Spotify – and BitCoin.

The blockchain is a shared, trusted, public ledger controlled by no-one and open to everyone. Hence the possibility of a currency without a central bank.

The ledger contains all transactions and is only updated when a significant majority of market participants agree. In theory it prevents double-spending and theft.

Blockchains are built around cryptography – code-cracking. Data is reduced to hash values, and if the data is tampered with, the hash won’t match any longer.

Ideas for the blockchain include public databases like registries, or ownership records for art works or luxury goods. Documents can be “notarised” in a similar public database.

Financial services firms also want to use blockchains to record ownership. This should remove the need to reconcile transactions with counterparties.

Twenty-five banks have joined a blockchain startup – R3 CEV – to develop standards. NASDAQ is about to using blockchain recording of deals in private companies.

The BitCoin model includes an energy-intensive “mining” process, which pays participants to provide the computing power needed to maintain the ledger. Private blockchains might find alternatives to this step

Incumbents – banks, clearing houses and government authorities – will no doubt oppose the new systems. But governments and banks are not so trusted these days, and perhaps there will be widespread demand for the new approach.

Lending to SMEs

The newspaper also looked at some data which suggests that Britain’s small firms – those employed less than 250, which account for 60% of private-sector employment – are not as credit-starved as people imagined.

Conventional thinking has been that in the financial crisis, banks cut credit to SMEs, which therefore struggled to find money to invest. This in turn held back productivity growth, leading to lower wages.

The outstanding stock of small business loans in September was 20% lower in real terms than in 2011 (when the BoE began recording SME lending). Overdrafts have shrunk even more, but make up only 10% of SME financing.

But this is mostly because firms have been repaying loans. New lending to SMEs is actually rising – it’s now 60% above the 2012 low. The average interest rate they pay is down, too.

The repayments suggest that SMEs have spare cash, from better than expected sales, and are not credit constrained after all.

- The banks are in better shape than they were

- The Treasury & BoE’s 2012 “funding for lending” scheme (FLS) has helped – it offers cheap money to banks which lend to firms in the “real economy” making and doing things.

- Small business owners are also raising cash against their houses, and via P2P lending.

But the FLS is due to expire in January, so things could change again. Especially if interest rates go up in 2016.

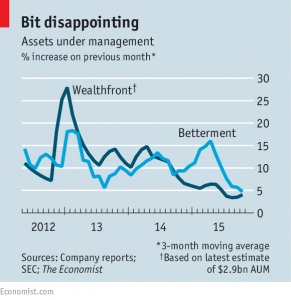

Robo-advisor growth slowing

It seems that robo-advisors will not be taking over the world just yet. We reported a couple of weeks ago on the main offerings in the UK (spoiler alert – none of them beat the DIY route).

Now the growth of the market leaders in the US is slowing.

At least the US options are competitively priced – Wealthfront (West Coast) and Betterment (East Coast) charge only around 0.25%. If that includes underlying fund fees, they could be attractive to many investors in the UK.

If not, a comprehensive ETF portfolio would add between 0.3% and 0.4% pa, while a simple tracker portfolio might only add 0.1% pa. So not bad, but not compelling.

The low (-ish) costs, low minimums and snazzy smart phone apps make them particularly attractive to the young. Which is a Good Thing, because the finance industry needs to attract them somehow, and they don’t seem too keen on the Old Ways.

The Economist points out their low margins. The two firms each have close to $3bn of assets, but generate revenues of only around $7M. Running costs – for around 100 staff each, plus marketing – are likely to be in the $40M to $50M range, so they are a long way from profits.

They need tens of billions of dollars in assets to break even, and were doubling every 7 months in 2014 (10% per month). That growth rate has now halved.

Incumbents like Vanguard and Schwab have launched competing services, and Schwab already had more than $4bn in assets (albeit from its existing customers).

If the big firms are willing to eat their own lunch, the small fry will have to raise prices or put themselves up for sale (which would probably have the same effect in time). BlackRock bought FutureAdvisor in August.

The robots will take over in some way, but maybe only by replacing humans at the firms that already dominate the market.

Valeant and dodgy accounting

Schumpeter looked into Valeant’s accounting troubles.

Valeant is backed by two hedge funds, ValueAct and Pershing Square. Its accusers are James Chanos, a short seller, and Allergan, a rival drugs firm it tried to buy in 2014. ((Herbalife, a direct sales firm / pyramid scheme – depending on who you believe – is also under similar attack ))

Valeant’s announcement that is hasn’t been massaging its figures is the latest in a string of similar issues: ((in addition, firms like Quindell and Globo have also collapsed on London’s AIM market ))

- IBM also said regulators were investigating how it books its sales

- Tesco, a British grocer, is on the rack after admitting inflating its profits

- Noble Group, a Singapore-listed commodities firm accused of questionable book-keeping saw its shares collapse

- Hong Kong’s regulators suspended trading in Hanergy, a solar panel firm back in May

The recent episodes total $80 bn in shareholder losses, around half the impact of the Enron, MCI-WorldCom and Parmalat collapses in 2001-03.

The current issues are less the outright frauds of a decade ago, and more creative accounting designed to paint an optimistic picture. Often only a small proportion of sales / profits / assets are involved.

Companies have in general become experts at spinning their numbers, perhaps because executive pay is now closely linked to share prices.

As regulators improve the rules, creative accountants remain a step ahead.

- The old tricks were to capitalise costs, which understates expenses and boosts profits, and to steal from the pension fund.

- Next firms issued debt disguised as equity (the banks before 2008).

- Now scandals often involve dealings with related companies presented as “arm’s-length” transactions.

Cash-flow statements are much harder to fiddle. Four of the current five firms have had weak cash flow. Other clues include paying low levels of tax and focusing on “adjusted” numbers.

Money makes you happy for a while

Finally, the Economist looked at a new study which shows that money can buy you happiness. The bad news is it only lasts for a year, and makes other people unhappy.

Economic growth is a good thing, but it breaks up families – as children move to the big cities – and makes jobs generally less secure.

China’s population was initially unhappy with the economic reforms there, until growth accelerated to the point that the benefits were obvious.

The biggest study of income and satisfaction concluded that they are correlated, but it’s not clear which one leads to which.

- Some believe that happiness comes first – depressed workers produce and earn less.

- Or perhaps they are both caused by the same thing – a wide circle of friends might make you happy and provide leads to good jobs.

To study this, social scientists use randomised trials. A lottery is a good way of randomly allocating extra wealth, but participation rates are quite low so those who play are probably not typical.

A fake lottery could get around this, but would be too expensive to implement here in the West. So they did it in Kenya instead.

- Average wealth there is around $400, and prizes ranged up to $1500, with an average of $350.

- Five hundred households spread across 120 villages were given prize money.

- Though not everyone received money, economic growth tends to provide gains unevenly.

To test well-being before and after they used questionnaires, screening for depression and saliva tests for the stress hormone cortisol.

- Those who received money were happier, but their neighbours became less happy.

- And their fall in happiness per $100 was greater than the recipient’s rise in happiness.

- The more handed out in a village, the more those with no handout were unhappy.

- Participants appeared to compare themselves to the rest of the village.

Hedonic adaptation meant that both recipients and neighbours were back to their baseline after a year.

Another study from Germany explains the results. It seems that people look exclusively at those better off than themselves. When others do better we react negatively.

More importantly, when our own lot improves, we merely start to compare ourselves to a richer reference group. We are never satisfied and quickly take our achievements for granted.

At the societal level this might be a good thing – envy could be what drives people to earn more, and economies to grow.

But at the personal level, keeping up with the Jones will not make you happy. You have to let go.

Until next time.