Weekly Roundup, 20th November 2018

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup in the FT, where John Redwood was concerned that the row about Italy’s budget was leaving the euro zone in limbo.

Contents

Italian budget

John noted that the October crash had hit Germany and China hard.

- He had moved his fund out of these countries in anticipation of the US-driven global trade war intensifying.

He has so far resisted the temptation to buy back in, and the fund is roughly flat for the year, whilst most markets (and investors) are well down.

Monetary tightening (mainly in the US so far, but possibly soon in the UK and Europe, too), a looming recession and a bang of an end to Chinese banking problems are also concerns.

- So are a possible slowdown in corporate profits growth and a sell-off of tech firms.

But John’s main worry is the stand-off with the EU over Italy’s new budget.

- The proposed deficit does not exceed EU limits, but Italy’s high level of national debt means that the EU want to see no deficit at all.

The EU also does not believe Italy’s assumptions and forecasts.

The ECB could refuse to finance the Italian commercial banks to the extent they want. This forces commercial banks to refuse access to customer deposits, or to ration the amount of money people can withdraw. It rapidly seizes up the economic system — which gets the attention of errant governments.

This is what happened with Greece, but the Italian economy is ten times larger.

If the row is resolved, John will buy more shares.

- But if it escalates, he will sell more shares (non-Eurozone, since he has run out of those to sell).

The Economist also had an article on the Italian budget crisis.

House prices

Merryn was worried that house prices might never rise again.

Fast-rising house prices in the UK are a relatively recent phenomenon. They have risen on average 3 per cent a year in inflation-adjusted terms since 1939 (a total of 834 per cent).

But before that they mostly fell — 50 per cent in inflation-adjusted terms from 1290 to 1939.

It’s all down to demographics, apparently.

- The smallpox vaccine of 1796 (from Edward Jenner) was the turning point.

Since then the rate of global population increase has gone up.

Merryn puts a lot of economic forces down to the life stages of the baby boomers:

Inflation and unemployment rose in the 1970s as the baby boomers began to both “jostle for their first jobs” and to consume global resources on a huge scale.

Stock markets to start to boom in the 1980s as those same boomers moved into their thirties and forties and started to pour cash into investments to finance their retirements.

And as the boomers started to form households, and look for bigger and better houses than the ones their parents had, property prices went up.

- But now they are more likely to be sellers than buyers.

And interest rates are likely to slowly drift up again.

- And the tax treatment of property – especially second properties – is becoming less benign.

So the next thirty years don’t look so promising.

Capitalist revolution

The Economist thinks that capitalism needs to change.

- Most of the things it didn’t like are worst in the US, but there is some read-across to the UK.

Young Americans have lost faith in the capitalism system, which rewards capital too much and labour too little.

Increasing market power, particularly for tech firms, means poor competition, fat profits and little need for reinvestment to fight off insurgents.

- There’s also an increasing risk of cronyism (corporate lobbying of government), even though this usually leads to a lack of innovation and a stagnation in living standards.

I see their point, but network effects make it difficult to argue in favour of rivals to firms like Google, Netflix and Amazon, or to approve of antitrust moves against them.

- Pharma firms, credit-card networks and airlines make better targets.

The Economist would like to see:

- Users owning their own data

- Corporates forced to licence anonymised bulk data to their rivals

- Rarer, shorter and easier to challenge patents.

They also want to get rid of non-compete clauses and occupational licensing requirements.

International bias

Investors in the UK – particularly younger ones – have got wise to home bias.

- They complain in online forums that Vanguard’s Life Strategy index funds have more than 20% exposure to the UK.

They favour “global” funds instead.

- But global means a 55% exposure to the toppy US market.

This has been a boon over the past decade, but won’t be forever.

- Which is why I prefer to construct my own allocations from multiple funds.

Buttonwood looked at the problem from the other direction:

- 75% of US funds are invested in their home country.

And of course US investors can’t diversify much by buying a global fund.

Buttonwood notes that the high global weighting of the US is not just down to high valuations, but also because a high proportion of US firms are publicly listed.

- In some other cultures more companies remain family owned.

The argument against more diversification is that when the US market sneezes, other stock exchanges catch a cold.

- Correlations increase significantly during crises.

But in the end, local growth counts, and a diversified portfolio will outperform the worst markets (and underperform the best).

Buttonwood recommends one-third US, one-third other developed economies and one-third emerging markets.

- I swap the UK for the US (since that’s my home bias) and have a bit less in EMs (and more in alternative assets), but my philosophy is quite similar.

Opportunity zones

The Economist came out against opportunity zones – what we used to call Enterprise Zones in the UK.

- There was also a second article here.

Investors get tax breaks for putting money into run-down areas than need re-development.

- Docklands was a big beneficiary a couple of decades ago.

I think they would be a great way of attracting money to the Northern Powerhouse and / or of getting a lot of houses built quickly.

- Of course, you’d still have the problem of making sure the houses (people) and jobs were roughly in the same place.

The 100 year life

The newspaper also reported on Japan’s plans to deal with unfavourable demographics.

- PM Shinzo Abe wants to make the country the “100-year-life society”.

This involves:

- Persuading people to work for longer

- Encouraging more women to work

- Immigration (or foreign “trainees”, as Japan calls them), and

- Automation.

Even all these may not be enough.

Bankrupt universities

The Economist notes that Britain may soon have a bankrupt university (assuming that the government has the stomach to let it go under).

- It should, because the sector is woefully bloated, and if the colleges think that they will be bailed out, they are unlikely to act prudently.

- Given the experience of failing schools (and banks) , I think takeovers by “better” universities are more likely.

Blair’s idea to send 50% of UK children to university may have been politically useful but it’s a terrible mis-allocation of resources.

- There are no longer any limits on student numbers, and each on is charged £9k pa in fees.

In a bid to attract lucrative but dim students, universities are spending not on research or teaching, but on improved facilities.

- This is the Butlin’s / Club 18-30 approach to recruitment – never mind the useless qualifications, look at our monorail / tiki bar.

The 130+ “universities” of the UK are now £12 bn in debt, up from £5 bn in 2012.

- 19 ran a deficit in 2016-17 (the latest year for which we have data).

Leeds, Liverpool, Cardiff, Manchester, Cambridge and Oxford have all taken advantage of low interest rates by issuing public bonds, raising £250m-750m each. The lowest-ranked universities struggle to find any lenders.

A squeeze is predicted as student numbers fall going into 2020 (because of historic birth rates).

- It will probably be harder to increase the number of foreign students to close the gap.

Virtual goods

The progressive infantilisation of life in the UK has been one of the greatest disappointments of my time as an adult.

The Economist’s latest bulletin from the frontline is that China is cracking down on video games because addicts are spending too much money on the virtual goods contained within them.

Much gaming now happens online, and generates reams of behavioural data. This allows publishers to monitor exactly how customers are playing games, and fine tune them to make them as compelling as possible.

It is an understatement to say that since virtual goods are free to produce, the profit margins are very high.

- Regulators in Europe and America are expected to act in due course.

I am reminded of Robin Williams’ joke:

Cocaine is God’s way of telling you that you are making too much money.

Food banks

The Economist also sought to explain why the use of food banks is surging.

This is no mystery to me – they give away food for free, and who wouldn’t want free food (and hence more money to spend on less savoury goods).

- The same argument applies to the famously “free at the point of use” – and hence congested – NHS.

The Trussell Trust now has 1,200 food banks, and gives out ten times the number of parcels that it did in 2011.

- The problem is that commentators use this activity as a proxy for the level of poverty in the UK.

Even the poorest people in the UK are rich in global terms, and anyone who lived through the 1960s can testify that people were much poorer then.

- According to the “relative poverty” measure used today, around 85% of us lived in poverty in the 1960s.

Yet we are still encouraged to see poverty as a massive problem in the UK.

The Economist suggests that the use of zero hour contracts and the rise of the gig economy means that low earners’ income has become less secure.

- This leads to short periods of time when people may need the free food.

Benefits sanctions and delays could be another factor.

Points of Return

John Authers was in good form for Bloomberg once again.

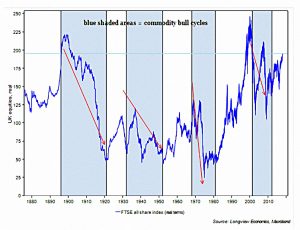

I liked his analysis of Kondratieff waves as they relate to Brexit.

- K waves suggest that stocks do well when commodities don’t, and vice versa.

But in the UK, there’s another overlay:

- The UK stock market has been flat since the end of Empire, but this period can be split in two.

- Until the 1970s, things were bad, and since then they have been pretty good.

People like me would attribute the recent success to the Thatcher reforms.

- But John points out that the recovery period also coincides with EU membership.

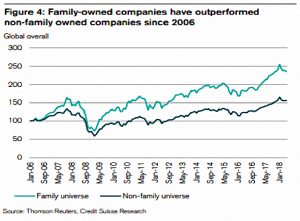

John also wrote about Credit Suisse research showing that the more control a family has of a stock, the better its share price will perform.

- This is something we’ve looked at before with our list of Family Firms.

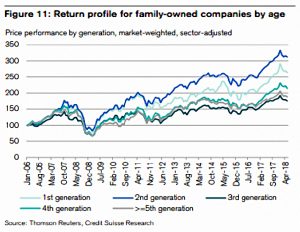

But the family effect diminishes over time as new generations take the reins. Companies controlled by founders or their children tended to perform significantly better than companies in the third through fifth generations of family ownership.

Quick links

I have six for you this week, the first two of which are from the Adventurous Investor:

- His Monday Macro post, including a feature on gold

- The rise of the killer batteries

- Alpha Architect asked whether Value and Momentum are dead.

- Interactive Investor looked at “hidden gem” investment trusts.

- Musing on Markets tried to work out if this was the end game for GE, and

- Money Week (David Stevenson again) looked at three alternative finance platforms making waves.

Until next time.