Weekly Roundup, 22nd December 2015

We begin the last Weekly Roundup of the year – next week’s edition will be a look back over 2015 – in the FT, with the Chart That Tells A Story.

Contents

UK wages growth

Sarah O’Connor looked at UK wages growth.

- After six years of slowing growth, 2015 was a good year for wages, with annual growth reaching more than 3% in the summer.

- But now the rate has started to fall again, to 2% in the three months to October.

Unemployment is at 5.2%, the lowest in a decade, and total employment is the highest ever. But the apparent shortage of workers hasn’t translated into more bargaining power and higher wages.

Inflation is part of the story, because flat prices could make even a 2% pay rise seem better. But many people complain that official inflation rates don’t reflect their experience “on the street”.

Another factor is the increase in young people (who tend to be paid less) finding work in recent months. Youth (16- to 24-year-old) unemployment is down to 13.6%, the lowest since 2005.

There is also some spare capacity in the labour market that is hidden by part-time employment – 16% of part-time workers (not that many, really) would prefer full-time work.

Some observers think that the 2008 crisis has had a lasting effect on workers’ confidence. A lot of salary increases are achieved by switching employers and people may be more reluctant to do that.

Does this matter much, apart from to the individual workers themselves? Only to the extent that interest rate rises in the UK will probably depend on inflation and wage growth firming up.

Fed rate increase impact

Ken Fisher looked at the likely impact of the first Fed interest rate increase in this bull market.

As usual, Ken is optimistic:

- The first rate increase hasn’t killed a US bull market since 1933.

- Ken even finds the fact that people fear that it might – a false fear – bullish in itself.

The 12 bull markets since 1993 have lasted an average 3.3 years beyond the first hike.

- Nine tightening cycles since 1971 have produced average returns (in £) of 10.8% for the next year, and 19.1% over two years.

Ken says that short-term rates on their own are not as important as the gap between the short- and long-term rates – the yield curve.

- A big spread encourages lending – as banks can earn bigger profits – and boosts markets.

So the big problem is when central banks overshoot and invert the yield curve (make short rates higher than long ones). This has happened before all of the seven most recent US recessions.

- But 10-year US Treasury yields are above 2% today, so even with the rate increase, the gap is large.

So everything depends on how quickly the Fed tightens from here.

- Janet Yellen appears to favour gradual tightening, and the US presidential election in 2016 may also make her cautious.

- She won’t want to upset the next president by tightening too quickly.

So Ken expects the US stock market to stay high next year.

Pensioner bonds

Neil Collins looked at the government’s decision to almost halve the interest rate on Pensioner Bonds. Neil sees the bonds as a pre-election bribe which is no longer needed.

The bonds had paid a high rate of 2.8% after one year. They were restricted to £10K per person, so that means a maximum of £280 in interest (£224 for basic rate tax-payers, or £168 for higher-rate tax-payers).

The new rate is 1.45%, somewhat lower than the top of the market.

While the old rate was high, it could be argued that it was intended to reward savers hit by seven years of financial repression (artificially low interest rates). Those unwilling to invest in risky assets – equities, property and even bonds – have not done well since 2008.

Tax complexity

Adam Palin wrote about the increased complexity that will be created by the new allowances for dividend and savings income.

The issue is that while income within the new allowances is tax-free, it still counts towards a person’s taxable income for the year.

Because of this it can take taxpayers over thresholds like:

- the higher rate tax boundary

- £50K, where child benefit is tapered

- £100K, where the personal allowance is tapered

For example, someone with non-dividend income of £100K and £4K of dividends would lose £2K of the personal allowance. That would mean 40% * £2K = £800 in extra tax.

- In effect, the dividend is being taxed at 20%.

Someone paid £40K with £9K of dividends will have to pay 32.5% on the last £4k of dividends, because the tax-free portion pushes their income to £45K and into the high-rate band.

Inequality

Chris Giles looked at new ONS data that showed UK wealth inequality has risen for the first time in almost a decade.

The data covers 2012 to 2014 and the main culprit is the rise in house prices in London and the southeast.

- The median household now owns £225K including pensions, or £141K outside of pensions.

- The wealthiest 20% now own 117 times more money than the poorest 20% – up from 97 times two years earlier.

- The share of national wealth held by the richest 15 held steady at 13.5%.

- The next 9% increased their share from 30.1% to 31.2%.

- The threshold for the top 5% is now £895K.

A quarter of people aged 55 to 64 live in households with more than £1M, compared to only 4% of 25- to 34-year-olds.

- The average for the population is 13%, with those with good qualifications and senior jobs best represented.

Couples without children – with one member over retirement age – had the highest average wealth, at more than £600K.

High yield bond funds

Over in the Economist, we were told not to worry about the emerging problems with high yield bond funds.

Back in August 2007, French bank BNP suspended redemptions in three funds representing only 0.5% of their assets under management.

- This was the first sign of the credit crunch.

Three high-yield (“junk”) bond funds have just done the same – managed by Third Avenue, Stone Lion Capital and Lucidus Capital.

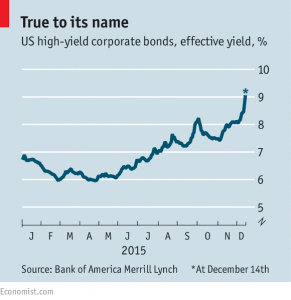

Prices of junk bonds have fallen this year, as yields have risen (see chart).

- When prices fall, investors tend to withdraw assets. ((Not always the best course of action, but a popular one ))

- Funds freeze redemptions in order to sell illiquid assets more slowly, at better prices.

People are worried not only about active funds and hedgies, but also junk bond ETFs. ETFs generally have good liquidity, even if their underlying assets don’t.

- But bonds have become less liquid since capital adequacy rules began to punish banks for holding them.

The Economist isn’t worried yet. The funds frozen in 2007 weren’t junk, and most of the problems are with energy and mining funds, who represent only 23% of the junk bond market.

Scrooge was right

In the first of several seasonal articles, Tim Harford looked at whether Scrooge was right.

Because a miser spends little, everyone else has more, just as if he had divided his wealth amongst the whole population. He quotes the economist Steven Landsburg:

There is nobody more generous than the miser – the man who could deplete the world’s resources but chooses not to.

Tim is reminded of the KLF, who burned £1M in notes on a Scottish Island in 1994. People were outraged, but as Bill Drummond – one of the pyromaniacs – pointed out:

Burning that money doesn’t mean there’s any less loaves of bread in the world, any less apples, any less anything. The only thing that’s less, is a pile of paper.

The money represented Drummond’s claim on £1M worth of goods and services and by burning the money, he relinquished his claim, allowing others to enjoy them.

- By reducing the amount of money in the UK, he made everything a little bit cheaper.

- Only in a deep recession would the reduction in demand have any consequences.

Scrooge was just the same as Drummond, apart from the burning.

Tim also mentioned The Deadweight Loss of Christmas, an article by economist Joel Waldfogel. This showed that present receivers value a gift at less than the giver paid for it. This is a waste of resources.

Follow up work has demonstrated that:

- givers rate spontaneous gifts above those from a list, but receivers feel the opposite

- people like to receive money but don’t like to give it

- givers think expensive presents are better, but receivers don’t

It’s not a great system really.

20-20 hindsight

John Authers wrote his annual column on the trades placed by the fictitious Hindsight Capital, the firm that only has winners.

To avoid limitless gains, John imposes some rules:

- no bets on single stocks

- no leverage

- no trades during the year

Here are some of the best predictions and bets they used in 2015:

- Short energy stocks and buy consumer discretionary stocks that would benefit from cheap oil

- this made 43.4%

- China’s slowdown would reduce commodity prices and produce deflation, which in turn would support long-dated bonds

- shorting the industrial metals index and going long the 7-10 year Treasury index produced 42.5%

- The rehabilitation of Iran would add to the oil glut

- shorting the energy index and buying more long Treasuries produced 69.4%

- Go long equal-weighted Fangs (Facebook, Amazon, Netflix and Google) and short the equal-weighted S&P 500

- this bet that the bull market in US stocks is drawing to a close made 82.8%

- Go long the market-weighted Nifty Nine (the Fangs plus Priceline, Salesforce, Starbucks, Microsoft and Ebay) and short the Russell 200 index of smaller companies

- this is another end-of-bull concentration bet, which made 72.6%

- The fall in commodities should benefit Japan, and hurt Latin America

- going long the Nikkei and short the LatAm index made 56.7%

- Selling the Global coal index and buying the clean energy index

- this bet on clean energy produced 156%

- Shorting Greece and going long Italy made 65.7%

- Short gold, long Bitcoin made 62%

2015 returns

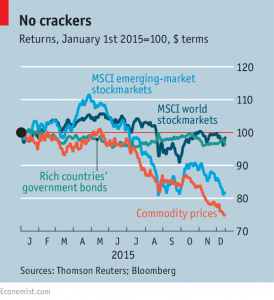

Buttonwood approached the same subject from the opposite direction, reporting on 2015 returns.

There isn’t much good news. Global economic growth for the year will be 2.9%, below the 3.6% average for the last 30 years.

- In dollar terms, global equity investors have lost 1.4%.

- Government bonds are down about the same amount, although the 10-year bond was slightly positive.

- Emerging market stocks are down 17.3%.

- High-yield bonds are also down.

- Gold lost 10% and the commodity index is down 26%.

Non-dollar investors did better (unless they hedged their currency exposures).

- Eurozone and Japanese stockmarkets were up in local currency terms, as were international stocks.

Even the low oil price hasn’t helped as much as expected.

- The effective tax cut has supported developed economies, but there have been no booms.

- And commodity producers have cut back on investment and added to corporate bond risks.

- Overall corporate profits are falling, and non-energy profits are just anout flat.

Falling profits and high valuations (especially in the US) mean that the prospects for stock markets in 2016 are not good. But almost everything else looks even worse.

Products wishlist

Chris Dillow put together a Christmas list of financial products he would like to see better developed in the UK:

- Care home / social care insurance

- UK factor ETFs (momentum, low volatility etc) – these are mostly global in scope at present

- Volatility tracking portfolios, which reduce equity exposure as volatility rises

- I would like to see something similar based on a valuation measure, which moved in and out of equities according to whether thy were cheap or expensive(eg. percentage above / below the long-term average for the Schiller CAPE)

- House price futures, to allow young people to gradually get on to the housing ladder, and owners worried about price falls to hedge their exposure

- GDP futures, and even securities tied to the income of particular industries or occupations – people could insure against a crash in their industry, or a lack of future prosperity

- An asset linked to aggregate corporate profits, including those of companies that don’t exist yet (eg. disruptive technology firms like robotics companies)

I must say that I like this list. Chris says that many of the ideas were first proposed by Robert Schiller.

The big question is why they don’t they exist?

- No doubt they would be a minority taste, at least in the beginning.

- This would both limit their benefit to users (through poor liquidity) and the profits available to their inventors.

- Chris also thinks that financial firms don’t innovate as much as they should because they can’t rely on brand loyalty to deliver them the rewards of innovation.

For whatever reason, these useful products aren’t here today. In which case, why doesn’t the state step in to a market failure and provide them itself?

Until next time.