Weekly Roundup, 20th August 2019

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup in the FT with Jason Butler, who was looking at money myths.

Money myths

We’re still in the holiday period, and things are still quiet in the financial press.

Jason had four myths, but I only agree with him about one of them:

- Pound cost averaging doesn’t usually lead to higher returns than lump-sum investing.

That’s because (equity) markets trend upwards, so you are likely to have missed out on some gains by the time you get all your money invested.

The first thing I disagree with is that investors don’t significantly underperform the funds they are invested in.

- He quotes Morningstar data that suggests the underperformance gap (in mutual funds, perhaps in the US) has shrunk from 4% pa to 0.26% pa.

This just jars with my experience of private investors, who are always chasing the hot sector/fund/star manager, and are likely to bail when times get tough.

- I can accept that the rise of passive investing has closed the gap overall, but I still believe that the subset of active private investors is underperforming.

Next up is rebalancing, which Jason says doesn’t help.

But we need to rebalance to stick with our target asset allocation.

- Since stock returns are higher than non-stock returns, our portfolios will drift towards a higher stock allocation.

In the sense that most people don’t have enough exposure to stocks, Jason is right that re-balancing might not be needed in practice.

- But in principle it is.

We have more on the topic – including a set of best practices – in this slide show.

The final topic is whether active portfolios give you a good chance to outperform the market.

There’s a lot to unpack in that simple sentence:

- What do we mean by active?

- What is the market performance?

- What chance do non-active (“passive”) portfolios have to outperform?

I would argue that there is no such thing as passive – the global asset portfolio is not investable.

- So we are all active investors of one sort or another.

I would also say that calling the performance of a market-cap-weighted index fund the market performance is misleading.

- Market cap indices have serious drawbacks and are straightforward to outperform (eg. with equal-weighted funds).

And I would argue that only “active” can outperform since “passive” must return the market performance minus costs.

- Of course, in aggregate, active must also underperform by the level of lits (likely higher) costs.

Factor strategies – whether implemented passively via funds or actively via stocks – can outperform, though not all of the time, and not all of the factors at any one time.

Jason has a very good idea for an article, but the topics he chose are not the low-hanging fruit that he imagines.

Ditching cash

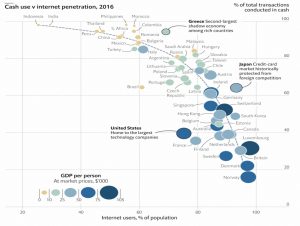

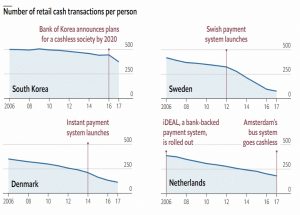

The Economist looked at the use of cash and found that it was inversely correlated with internet penetration.

- Other factors include government and corporate support – London and Amsterdam have banned cash payments on buses – and technologies like contactless payments and fast inter-bank payments.

Anxious markets

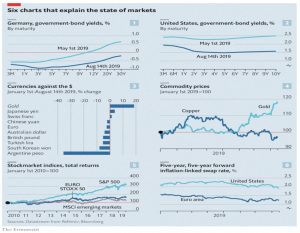

The newspaper also wrote about investor anxieties over the prospect of recession, and a second article has some illustrative charts.

- The financial markets have a track record of complacency about potential dangers, but the dominant mood of the past decade has been anxiety.

This shows up in the crazy appetite for “safe” bonds whose yields have in many cases been pushed negative.

- Even Italian 10-year bonds yield only 1.5% pa.

The safe-haven dollar is up against most currencies and gold is at a six-year high.

- Copper and oil are down.

But the Economist is not convinced that a recession is inevitable.

- The global economy is still growing, there are lots of jobs around, wages are increasing and credit remains easy.

They suggest watching three warning signs:

- the dollar – the more people buy this as a safe haven asset, the more worried they are

- the US-China trade negotiations – Trump probably needs a deal to get re-elected next year, but China might prefer its chances with a Democrat successor

- the corporate bond yield spread over Treasuries, which is widening – a further increase would put pressure on indebted firms that need to rollover their borrowing

If instead, the anxiety dissipates, we might face a surge in bond yields, a crash in high-priced defensive stocks and a rally in cheap cyclicals.

Inversion

Over on Bloomberg, John Authers had a bumper week, with three articles worth mentioning

The first was about the US yield curve inversion, which we’ve covered already.

- John’s point was that we’ve never had an inversion when rates were so low, which makes it difficult to interpret.

He also says that much of the bond buying is for reasons other than expectations

about the future path of interest rates:

Falling yields make it harder for pension funds to guarantee an income. Many around the world are now obligated by regulators to buy bonds to be sure that they can meet their liabilities, which helps to create a vicious circle.

Further, much of the current buying is part of a straight “carry trade,” as investors desperately try to find a positive yield somewhere.

And says we can’t ignore Soros’ reflexivity – the inverted yield curve has real effects whether we like it or not.

He concludes:

It would be wise to take this yield curve inversion seriously.

But we needn’t panic – bear markets usually begin several months after the inversion, and on average the S&P rallies a further 20% before it peaks.

- We might even make it to a Trump re-election in November next year.

Bond bubble

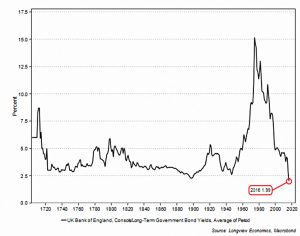

Next up was the bond bubble, which meets the four criteria of Charles Kindleberger:

- underpinning by cheap money

- debt-fueled price increases (eg. buying on margin)

- John uses the purchase of sovereign debt by central banks using newly created money to satisfy this one

- high valuations

- a narrative to explain the high prices (“this time it’s different”)

- This is the Japanification of the world, as central banks continue to print money and cut rates.

The chart shows the yield on UK consols going right back to 1700.

- It comes from a paper by Chris Watling of Longview Economics, who says of negative yields:

If borrowers don’t pay for the privilege of borrowing money, capital allocation discipline should then break down, as the rate of return hurdle for new projects falls (or even potentially turns negative).

The thing that almost always bursts a bubble is the removal of cheap money, which doesn’t appear to be around the corner.

Bond proxies

John’s third article was about bond proxies – boring companies with relatively high and consistent yields.

- Along with real-estate and utilities, “quality” companies (with sound balance sheets) tend to fit the bill.

Of course, when everyone is after the same kind of asset, it tends to become overpriced and therefore risky.

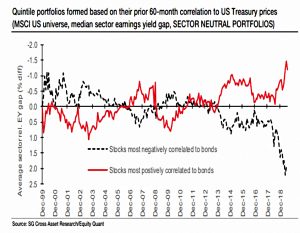

- Andrew Lapthorne at SG has shown that bond proxies are now at their most expensive point during the last seventeen years.

A sector-neutral analysis makes things look even worse.

- The obvious answer would seem to be to buy the “anti-bond” stocks.

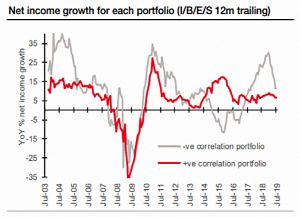

One thing is clear – the bond proxies are not recession-proof.

Quick links

I have seven for you this week, of which four are from The Economist:

- The newspaper looked at what comes after Bretton Woods II?

- And at the Viacom/CBS merger

- And at the WeWork IPO

- And at BooHoo’s business model

- Alpha Architect asked whether Time Really Is Money?

- ERN looked at the Great Bond Diversification myth, and

- The FT said that Infinite Growth is a pipe dream.

Until next time.