Weekly Roundup, 26th December 2022

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup with the coming housing crash.

Housing crash

The Economist looked at the countries where the housing crunch might be most painful.

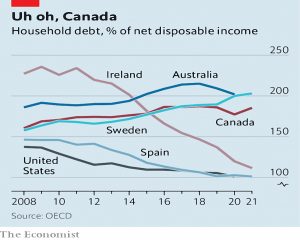

- It’s mostly in the places that sailed through the 2007-2009 crash – Australia, Canada and Sweden.

A mortgage binge fuelled by rock-bottom interest rates has left each country with enormous quantities of household debt. As a share of disposable income, such debt sits at 185% in Canada, 202% in Australia and 203% in Sweden.

The countries that did badly last time (America, Ireland and Spain) have paid down their debts.

In Australia, Canada and Sweden home prices have more than doubled since 2007, compared with rises of 50% in Britain and 61% in America.

The previous winners are more vulnerable to job losses and interest rate rises, as well as house price falls.

Australia’s central bank forecasts a 20% fall in house prices, which would be the biggest decline in four decades. Prices in Canada could plunge by as much as 14% from their peak, according to the Royal Bank of Canada.

Hermione Taylor looked at the same topic for the Investors’ Chronicle.

- She also came up with Canada and Australia as the markets most at risk, as well as the UK.

Goldman Sachs economists forecast significantly greater “payment shocks” for the UK, Canada and Australia than for the US, where 30-year fixed mortgages are common.

Things are obviously different here – most people have two- or five-year fixes.

A Deutsche Bank study looked at a range of factors to rank the markets most at risk.

The UK is currently mid-table: interest rates may have risen fast, but household debt as a proportion of household income is ‘just’ 148 per cent, and only 28 per cent of households have a mortgage at all.

The situation looks worse for Australia, ranked second most risky. The outlook is also gloomy for heavily mortgaged Canada, which tops Deutsche Bank’s risk table.

It’s good news that the UK is unlikely to be worst affected, but from an investor’s point of view, shorting the Swedish, Canadian and Australian markets is likely to be significantly more difficult than betting against the UK or the US.

80s playbook

The Economist wondered whether today’s politicians have the stomach for the 1980s playbook for dealing with inflation.

There are three lessons from that decade:

First, inflation can take a long time to come down. Second, defeating inflation requires the participation not just of central bankers, but other policymakers too. And third, it will come with huge trade-offs.

The path back to central bank inflation targets may be long and/or bumpy.

In 1980-81 rich-world inflation fell, but progress came to a halt in 1982-83. Then in 1987-88 there was another inflationary spike, fuelled by energy costs. In only 53% of months in the 1980s did inflation in the average rich country decline relative to the previous month.

And central banks can’t do it alone:

The liberalising reforms of the 1980s helped in the fight, increasing competition and thereby lowering prices. These reforms, though, probably took some time to kick in.

And monetary policy won’t work alone:

Policymakers across the world recognised, as they had failed to do in the 1970s, that loose fiscal policy could add fuel to the inflationary fire. They held back on spending even as households’ real incomes declined.

And a soft landing is unlikely:

Average unemployment across the rich world doubled in the five years after 1979. Home construction fell by a fifth in 1980-82.

After austerity in the 2010s and the handouts of Covid do today’s policymakers have the stomach for the 1980s fixes?

Many politicians now seem uncomfortable with the notion that anyone should lose out from anything, ever. They are offering hundreds of billions’ dollars-worth of deficit-financed fiscal support that will fuel inflation, whether by subsidising energy bills (in Europe), offering “cost-of-living payments” (in Australia and New Zealand) or forgiving student debt (in America).

Things don’t look great at the moment.

Financial advice

In the FT, Moira O’Neill looked at whether financial advice is value for money.

- The trigger for the article was the announcement from the FCA of a new simpler kind of advice called “core advice”, aimed at those with just £10K to invest.

Just 8 per cent of UK adults have taken financial advice over the past year and the regulator thinks this isn’t enough.

Sarah Pritchard, executive director of markets at the FCA, said:

These proposals are part of our work to deliver a consumer investment market where people can readily access support and firms aren’t deterred from providing it.

Around 3M people claim to have a relationship with a financial advisor, though it’s hard to see what benefit they can be gaining.

There are more than 36,000 retail investment advisers, a number which has grown steadily over the past seven years, according to the FCA. But these advisers are working in a shrinking number of firms with the larger financial advice firms getting bigger. FCA data show firms with more than 50 advisers accounted for 49 per cent of all adviser posts in 2021, compared with 45 per cent in 2018.

It’s also difficult to see how the economics can stack up at this lower level.

- Anybody worth listening to will want upwards of £1K for reviewing someone’s financial position, which rules out those with pots smaller than £100K. (( Many in the industry and the media like to say £50K is the lower limit ))

The FCA found in 2020 that total annual fees — covering advice and investment charges — are 1.9 per cent. A 2 per cent fee can wipe out 40 per cent of your investment returns over 25 years, according to calculations from Vanguard.

Those at the lower end need to learn enough about the topic to go DIY (or find a friend or relative who can do that on their behalf).

- The second trick is not to give in when your assets finally do climb above £100K – instead, stick with the DIY route.

Growth capital

The Economist said that small pension funds could be the UK’s best source of growth capital.

Britons’ insurance and pensions savings might be put to use driving domestic growth. Until relatively recently, they were: in 1998, 73% of Britons’ pensions savings were invested in British equities.

This figure is now 12%, and less than 1% of pension and insurance assets are in unlisted UK stocks.

- 90% of venture and growth fund money comes from foreign investors.

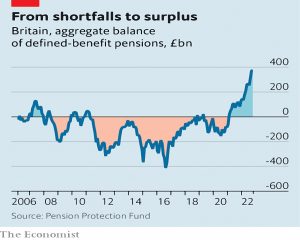

DB pensions hold £1.5 trn, of which just 2% is in UK stocks.

This is largely because these assets no longer need to seek returns. Though plagued by underfunding for much of the period since the financial crisis of 2007-09, db pension funds are now £375bn in surplus.

And there is fallout from the LDI crisis over the summer:

Many used LDI strategies to hedge their liabilities, freeing up capital to invest in equities and other risky assets. Regulators are pushing them to maintain chunkier cash buffers, reducing their scope to provide growth capital.

On the other hand, proposed reforms to Solvency II will reduce the buffer that insurers need to hold, potentially unlocking £100 bn for investment.

But allowing insurers to earmark less capital for future liabilities gives them many options: to invest in British projects or foreign ones, or to return cash to their shareholders as dividends or share buy-backs. Much of the £100bn may well go elsewhere.

DC pension pots “only” amount to £500 bn, but they might be a better option.

- Since payouts are not guaranteed, they have the incentive to seek high returns.

So stocks are on the menu, but not necessarily UK ones, or unlisted ones – though maybe they should be:

A 22-year-old entering a dc scheme and allocating 5% of it to venture-capital or growth-equity funds could expect to increase their total retirement savings by between 7% and 12% (compared with the mix of listed equities and bonds in a default scheme).

The main obstacle to this is the 0.75% pas fee cap on funds within workplace schemes.

- This is too low for VC funds, and performance fees are also outlawed.

The government is working on removing this obstacle.

Retail savers show an increasing fondness for investing in causes that promise good social outcomes. They might grab the chance to support domestic regeneration, too.

Premium Bonds

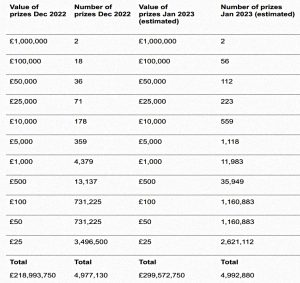

The prize pool on Premium Bonds will be increased in January 2023 from 2.2% to 3%, taking the monthly prize fund to just under £3M.

- This means the payout rate will have more than doubled in four months – it was 1.4% in September 2022.

The odds of winning a prize will not change (at around 1 in 24,000).

- If you have the maximum number of bonds (£50K) you can expect to win two prizes each month (usually £25 each).

So an average year’s winnings might be £600, or 1.2%.

From January, the number of larger prizes will increase:

- there will be 56 prizes of £100K rather than 18

- there will be 112 prizes of £50K rather than 36

But there will still only be two £1M jackpots each month.

Lovemoney had a summary table of the prizes:

Remember that premium bond wins are tax-free (as well as government-backed) so the headline rate is equivalent to 3.75% pa for a basic-rate taxpayer on a taxable account or to 5% pa for a higher-rate taxpayer.

Crypto

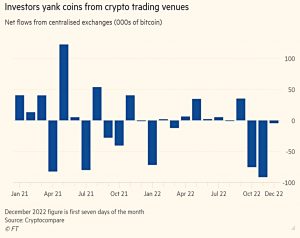

In the FT, Nikou Ansari reported on record withdrawals from crypto exchanges.

Last month investors pulled 91,363 bitcoin, worth a total of close to $1.5bn from centralised exchanges including Binance, Kraken and Coinbase. That marked the largest bitcoin outflow on record.

It’s not known how many coins are being sold back to fiat currencies, and how many are just being moved to private wallets.

A key driver is the bankruptcy of FTX – which has potentially more than 1M creditors – in November after an $8 bn hole was discovered in its accounts.

- Another consideration is the collapse of the bitcoin price to $17K, a fall of 64% this year.

Quick Links

I have just one for you this week:

- Alpha Architect looked at the Performance of Multi-Factor Long-Short Portfolios in Various Economic Regimes

Until next time.