Weekly Roundup, 3rd January 2023

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup with a look back to last year.

Hindsight Capital

At the end of each year, John Authers looks at the most successful trades made by his mythical investment firm that has the benefit of hindsight.

- To avoid the returns being infinite, individual stocks are not allowed, and neither is leverage.

- Illiquid markets and trading within the year are also out.

- Shorting is allowed, however.

- And trading costs and interest on shorts are ignored.

- John also insists that there was a rationale for the trade on 1st Jan – the fund is not allowed to take advantage of complete surprises.

This year there are twelve winning trades, based on four key insights:

1. Vladimir Putin really would invade Ukraine;

2. China’s economy would take a hit from the omicron variant;

3. Inflation would prove intractable (aided in part by the first two factors); and

4. Low rates had left many securities around the world wildly overpriced.

I would personally class the first two as modest surprises, but I suppose some less than 50% bets are allowed.

The first trade is the War Dividend – long S&P defence stocks and short Ukraine.

- This made 224%.

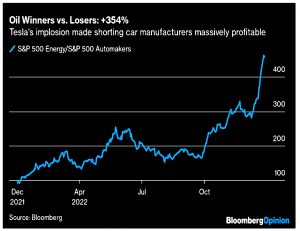

The second trade was oil – buy S&P energy and sell car makers.

- This made 354%, helped by the collapse in the Tesla share price.

The next trade was on strongmen presidents – long Turkey and short Russia.

- This made 234%.

Trade number four was another fossil-fuel trade – long oil and gas and short global wind.

- This made 101%.

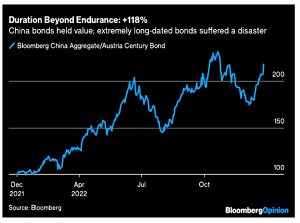

Next up is duration – as interest rates rise, long-duration bonds should suffer.

- Long Chinese bonds and short the Austrian Century bond made 118%.

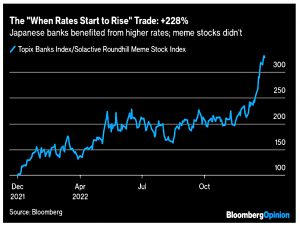

The second bet on rising rates was that stock inflated by cheap money would go down.

- Selling meme stocks and buying Japanese banks made 228%.

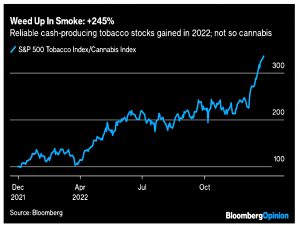

The seventh trade was long tobacco and short cannabis.

- This made 245%.

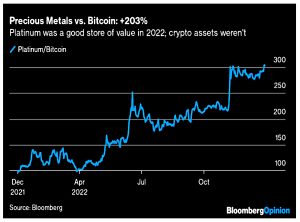

Next up was bitcoin, which was sold against Platinum.

- This made 203%.

The next trade involved buying default insurance against US Treasuries.

- This is an improbable scenario.

[But] only a slight rise in perceived risk can lead to a big percentage gain for anyone who has bought insurance against such an event. The massive fiscal splurge since the pandemic obviously makes it harder to keep servicing all of the federal government’s debt.

But much more importantly, the chance that the country could choose to renege on its promises and stop paying is perceived to have risen since the midterm elections.

That’s because the Republican majority in the House might block an increase to the US “debt ceiling”, which will be needed at some point in 2023.

- Meanwhile, Turkey’s financial position improved throughout the year, so the trade was balanced by selling Turkish default insurance.

Trade number ten was the carry trade – borrowing in a weak currency and parking the money in one with higher yields.

- This year selling yen and buying the Brazilian real made 38%.

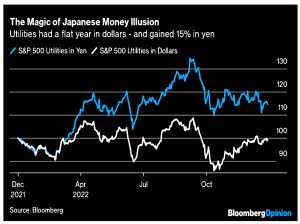

The Hindsight team also based itself in Tokyo to take advantage of the “money illusion” that comes from denominating returns in a weak currency.

- The US utility sector was down 1% in dollar terms, but up 15% in yen.

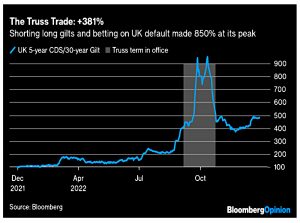

The final trade of the year comes from the UK.

- Shorting long gilts and betting on UK default made 381%.

Deadweight of gifting

The Economist looked at whether it might be better to give cash rather than gifts at Christmas.

The average British adult splurged around £550 on gifts in 2021. But a back-of-the-envelope calculation suggests that the volumes of unwanted stuff in effect destroyed around £3bn of the £25bn value.

This “deadweight loss” was first identified in 1993.

- It’s the difference between the costs of gifts and how much their recipients value them.

The current estimate is an average 15% loss.

Gift cards can help, but Brits don’t seem to like them (only 29% of people planned to give one this year).

- Easy returns (for eg. fashion) can also help, but these cost retailers, who are starting to charge customers,

Another problem is that some goods (eg. toys) are largely sold at Xmas.

- This means that temp workers must be hired and then fired.

Logistics firms also have seasonal peaks that can lead to unused capacity at other times of the year.

But the impacts are slowly falling.

- Compared to the 1980s, seasonality in clothing and restaurant sales has reduced, as has seasonal employment.

Looking back

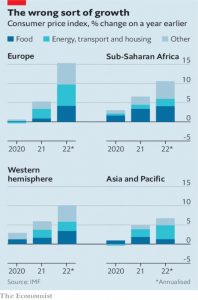

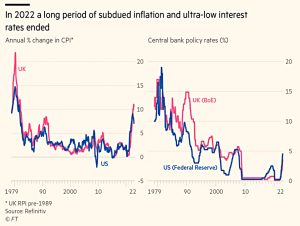

The Economist declared that 2022 has been a year of brutal inflation.

Just about every country in the world has grappled with soaring prices in 2022. The situation is all but certain to improve in the coming year, but at a severe cost to economic growth.

The global rate for 2022 was around 9% – it hasn’t been that high in rich countries since the 1980s.

- Fuel and food were the key drivers from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, with consumer goods already expensive from Covid-driven supply chain issues in 2021.

But now inflation has spread to core goods and services.

- And labour markets are very tight, partly because of Covid-influences early retirements.

That means high wage settlements, which contributes to more inflation.

- If this continues a wage-price spiral is possible.

Another factor underlying inflation is an excessive stimulus (low interest rates and money printing) from governments and central banks.

One way of looking at inflation prospects for 2023 is as a duel between rebounding supply and falling demand. Promisingly, some of the factors that fuelled inflation early in 2022 have started to fade.

Supply chains and consumer goods prices are returning to normal, and an increase in oil production is pushing the price of that commodity down.

- Higher interest rates are starting to choke off demand, and property markets are seizing up.

But it’s unlikely we will have a soft landing.

In 2023 fears of inflation may give way to concerns about unemployment.

The newspaper also described 2022 as the year of the rate shock.

- The Fed claims that interest rates won’t be lowered until its 2% inflation target is within sight. Jerome Powell said:

The historical record cautions strongly against prematurely loosening policy

Markets are hoping for a rate cut around mid-2023, but they have been disappointed after most Fed meetings in 2022.

- The five worst weeks for US stocks (each showing falls of around 5%) were immediately before or after a Fed meeting.

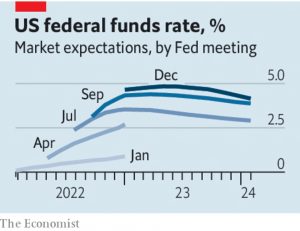

In January, peak rate expectations were at 1% – by December they had reached 5%.

The Economist sees the end of free money as the underlying cause for:

- the collapse in tech stocks

- the seizing up of bond markets

- the UK pension fund crisis in the autumn, and

- the collapse of the fraud at FTX.

And there might be more shocks to come in 2023:

The central bank reckons it may have to raise interest rates above 5% in 2023, and leave them there. That does not tally with investors’ expectations. They are betting on a shallower peak and continue to think that the first rate cut may come as soon as the summer.

Charts

The FT attempted to tell the story of the year in charts.

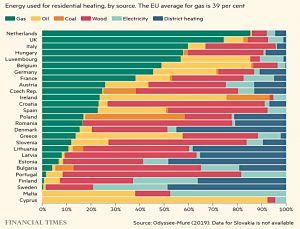

The Netherlands and the UK are the most dependent European countries on gas for heating homes.

As discussed above, inflation is at a 40-year high and interest rates are rising.

A moderate hole remains in the UK’s finance even after the Hunt Budget.

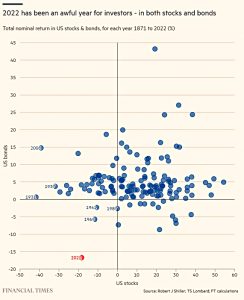

2022 was an awful year for both stocks and bonds.

The long-established 60/40 investment strategy was hit with its worst year since the 1930s.

Chartr also had some charts of interest.

The Fed is hiking faster than at any time in modern history.

The USA, Canada, Saudi Arabia and Russia account for 49% of global oil production between them.

And most S&P 500 sectors did badly in 2022, apart from energy.

Vanguard Managed ISA

Vanguard has launched a managed ISA in the UK, which seems an odd fit with the rest of its products.

- It sounds like a robo-advisor offering, but apparently, it’s an actively managed solution run by real humans.

That said, the service does involve a risk assessment which funnels the investor into one of five portfolios, each made up of low-cost index funds.

- Which is just what most of the robo advisors do.

Adjustments are made to the portfolios on a monthly basis, and investors can’t choose their own funds, or buy and sell within the product.

- If an investor’s circumstances change, they can chat with “investment experts” to find out if one of the other portfolios might now be a better fit.

The total cost is 0.6% pa, split into 0.3% management fee, 0.15% platform fee and 0.15% fund fees.

- There’s a cap on the non-fund fees of £1,125 pa, which means that percentage fees will fall for portfolios larger than £250K.

The minimum pot size is £500, or a £100 monthly payment.

I’m not a Vanguard customer, and I can’t see any need for this product.

Quick Links

I have two for you this week:

- Alpha Architect looked at the Expected Returns to Green Stocks

- And Bloomberg collated (Almost) Everything Wall Street Expects in 2023

Until next time.