Weekly Roundup, 27th February 2018

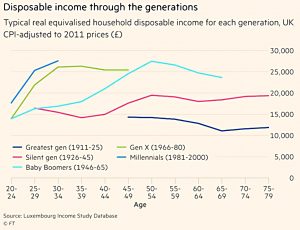

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup in the FT, with the Chart That Tells A Story. This week it was about disposable income by age, across generations.

Contents

Disposable income

Sarah O’Connor’s piece was entitled “Millennials poorer than their parents“.

- Unfortunately, that wasn’t what the chart showed.

Through the 20th century, each generation had more money than the previous one.

- That’s still the case, though the gap between the millenials and the Gen-Xers is smaller than some others.

The chart is before housing costs, but even so, if house prices were to continue to rise (and more millenials were buying than renting) that might not be a problem.

- After housing, millenials are slightly poorer than Gen-Xers of the same age (but richer than everyone else).

And of course, millenials are more likely than previous generations to inherit a lot of money (since their parents currently own the houses that have become so expensive).

- But this won’t happen soon enough to help them raise their own families – the average age of inheritance is expected to be 61.

Further, the inheritances won’t be evenly spread.

- Some fortunes will be spent on care homes, and other will have parents who never bought a house, or who live in a low-cost area.

How all this adds up of course depends on your own position in the game.

- But I know that the world today is a lot better than when I turned 30.

And if anyone young is willing to swap their life expectancy for my cash, I’m interested.

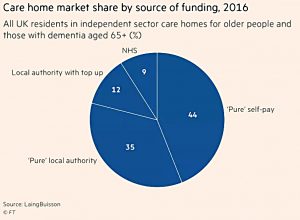

Choosing a care home

Rosie Carr – the assistant editor of the Investors Chronicle, wrote about ten things that she wished she’d known before she chose a care home.

- Around 421K people over 65 now live in a care home.

- The average cost in the south east is more than £1K per week.

Around 44% of people pay their own fees, and another 12% pay some fees.

Here are Rosie’s ten things:

- Be pushy with your parent(s) to find out about their medical and financial history.

- Talk about what kind of care will be needed and how it should be funded.

- Don’t assume that you’ll need to sell the family home (if there is one).

- If one parent still needs to live there, the local authority must disregard it.

- Even with a lone parent, a “deferred payment agreement” can be set up.

- Put a lasting financial power of attorney in place, before your parent’s mental capacity is affected.

- Afterwards, you need to apply to the Court of Protection to be appointed as a deputy.

- Poor people don’t pay.

- The definition of poor is laughably low, though – less than £23K in assets for “free” care.

- And the local authority will siphon off your parent’s pensions.

- Those with between £14K and £23K make partial payments.

- Medical conditions like a stroke (but not dementia) can make residential care free.

- State help has downsides

- The local authority will have a cap on their weekly payment, which means that you will only get a good home by using a top-up.

- Note that this top up can’t come from your parent’s money, on which the local authority now have a claim.

- If you later can’t afford the top-up, you’ll have to move your parent to a cheaper home.

- Deferred payment agreements (DPA) can help

- There are relevant state benefits, and they aren’t means tested or taxed.

- Attendance allowance is £83 per week.

- NHS nursing care contribution (NCC) is £155 per week, but only applied to medical cases (not dementia).

- But of course if the local authority is paying, they get the benefits.

- An annuity can help

- But only for really old people – younger people are unlikely to get their money back.

- The Society of Later Life Advisers (Solla) can find you a specialist in this area.

- Consider equity release, if you have a property.

- You’ll need one parent to still be living there, and there to be no outstanding mortgage.

- But there won’t be too many circumstances where this is the best option.

- Solla can help with tax and legal matters.

- But since they are financial advisers, there will be fees to pay.

Low volatility funds fail

Kate Beioley reported that low volatility funds had failed to protect their investors during the recent stock market sell-off.

- BlackRock and State Street’s US low volatility funds fell by 4% when the S&P 500 fell by less than 3%.

I’m a fan of smart beta in general, including Low Volatility (see my articles on Low Vol here), so in theory this is worrying news.

- In practice, the gains I expect from smart beta will accrue over years and decades, not a few weeks.

No strategy works all of the time, and the possible turning point of a 30-year interest rate / bonds bull market is not likely to match well with historic volatility data (on which the Low Vol funds are constructed).

- The best way to protect against the inevitable short-term shocks in the stock market is to have a cash buffer, so that you can ignore the markets.

Zopa warns over defaults

Kate’s second article of the week covered Zopa’s warning over increased P2P defaults.

- Zopa was the market pioneer back in 2005 and is the largest player in the consumer part of P2P.

It used to operate a protection fund against defaults, but abandoned this approach in 2016.

- Since then, defaults have increased from less than 3% to around 5%.

Net returns are down to 4.7% pa.

The great rotation

Maike Currie is convinced that the great rotation (from growth to value stocks) is finally underway.

- The drivers are increasing interest rates and rising inflation.

Rising bond yields reduce the attractions of “bond proxies” (pharma, consumer staples and utilities).

- And more inflation will reduce the debts of highly geared companies.

But at this stage of the economic cycle, can cyclical stocks be more attractive?

Maike sees the rise in consumer staples (which exceeds the rise in the broader index) as being driven by easy money looking for a safe home.

- Staples have re-rated rather than reported increased earnings.

Her tips going forward are supermarkets, leisure stocks, cinemas, pubs and holiday providers.

In his latest update on the ETF portfolio he runs for the FT, John Redwood was confident that shares would weather the temporary storm.

- As it happens, he had become overweight in stocks after a good run, and had just sold to move into short-term bonds before the sell off took place.

Here’s the current state of the portfolio:

Zombie companies

Tim Harford looked at zombie companies, which he defined (using research from the BIS and the OECD) as companies that don’t make enough money to service their debts.

- I think that a better definition is companies that do make enough money to service their debts under the current financial repression (interest rates below inflation), but which would go bust if / when we return to historically normal interest rates.

The proportion of zombie firms has risen from 2% om 1987 to 10% today.

The problem with zombies is that they divert resources from more useful and worthy competitors.

- They also make it harder for new startups to join a market.

Tim uses recently-collapsed Carillion as an example:

- As it struggled to remain profitable, it became more desperate to win new business.

This lead to aggressive bids that starved other firms of work and contract wins that proved impossible to fulfil.

Of course, bankruptcy can be a painful process for those involved, and a dead zombie is no use unless it is replaced by a more dynamic firm.

- So as well as getting interest rates up, we need to make it easier for new firms to flourish (via infrastructure, easy finance and the removal of red tape).

Charity

Merryn’s column was about charitable giving.

Before discussing the article, I should declare that I used to work in one of the largest and most popular charities.

- My experiences have soured me against the sector forever.

Merryn’s not too keen, either – she sees the tax breaks as undemocratic.

- The more tax relief they claim, the more the rest of us have to pay for everything else.

- Total subsidies now amount to £6 bn a year in the UK.

I have to agree, and I’m particularly irritated by four kinds of charity:

- Churches

- Private schools

- Political pressure groups masquerading as aid workers (eg. Oxfam)

- Anti-science groups like homeopathic charities.

Merryn singles out churches and the anti-science groups.

The system is very open to abuse, and many charity workers earn many multiples of the average wage.

The problem is that someone might object to any charitable cause, just as someone might object to any use of government funds.

- It’s a bit of an “all or nothing” situation, and I suspect that while I would be happy to see charitable status abolished, most people have at least one charity that they would like to see getting favourable treatment.

Which is why the UK has more than 185K charities.

Timing the market

John Authers wrote about timing the market.

- It’s a tricky subject for John, since he doesn’t believe in market timing (he thinks that trading costs usually outweigh the gains).

Yet his column is largely about how to spot market turns.

He notes that simply switching between stock and bond ETFs is madly profitable with hindsight.

- But would you have made the right timing calls?

And would you have been brave enough to take on all the risk?

Victor Haghani at Elm Partners in London suggests instead “expection-driven sizing” as part of “active indexing”.

- He suggests using trends and mean-reversion techniques.

For example, the CAPE has good predictive power of 10-year returns (but is almost useless in the short term).

But Dimson, Marsh and Staunton (of Credit Suisse Yearbook fame) suggest that mean reversion “in sample” (as you experience it) is difficult to pull off.

- A wild deviation from the trend will pull the trend towards itself.

They found that buy and hold worked better than using this deviated trend.

John also quotes Meb Faber’s work on rebalance portfolios over 40 years.

- We looked at that work here (in an article that’s already three years old).

Rebalancing (sell high, buy low) is a form of market timing, but the gap between the best and worst portfolios was “only” 1.5% pa.

- That reinforces the importance of costs (see here) but 1.5% pa is well worth having over 40 or 50 years.

John concludes that market timing is not dumb, but we need to accept the limits on our ability to do this, and we should not pay too much in doing it.

- I plan to return to this theme over the coming weeks with a “SMART MATS” portfolio, so stay tuned.

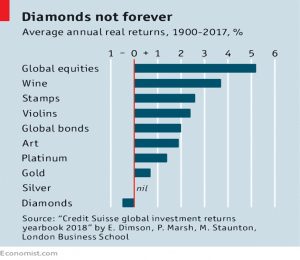

SWAG

Buttonwood looked at the returns from iInvesting in the finer things of life – or as I tend to call it, SWAG (Stamps, Wine, Art and Gold).

- We previously looked in detail at Stamps, but decided that the costs were too high.

Transaction costs tend to be very high on SWAG, and there are also storage / insurance costs to consider.

- The only way to offset these is to use a very long holding period.

Tax is also an issue, compared with the friendly treatment of a global multi-asset portfolio held within a SIPP and / or an ISA.

- But before the current / recent regime, tax worked to the advantage of SWAG in comparison to financial assets.

This might partially explain why SWAG has been historically popular with the very rich.

- But there’s also an emotional return (the “hobby” aspect).

The Economist article looked at the returns found in the Credit Suisse global investment-returns yearbook (from Elroy Dimson, Paul Marsh and Mike Staunton of the London Business School – as mentioned above).

- You might have guessed by now that the 2018 version was released last week.

The bottom line is that SWAG returns are decent – apart from gold, which was only useful during high inflation – but they are not as good as those from equities.

- So unless you have a good reason, you don’t need them.

The LBS yearbook also debunked a recent paper suggesting that returns from real estate were as good as (and less volatile than) those from stocks.

- That study played down agency fees, rental voids and the cost of improvements to properties.

The global real return on equities since 1900 has been 5.2% pa, but the authors suggest that a more realistic return going forward is 3% pa.

Passive funds

A couple of weeks ago, Buttonwood looked at how passive funds lose out when the composition of the index that they track changes.

- This finding (in a new paper from Lasse Pedersen of AQR) could give hope to active fund managers.

Movements in and out of indices (plus new firms and share buy-backs) mean that there are no really passive funds.

- A fund that had taken no corrective actions since 1986 would now own less than half of the US market.

The average turnover in the S&P 500 is 7.6%, which should cost a “passive” investor around 0.25% in trading costs to recover.

- That’s clearly not enough to increase the costs of passive funds to those of actives.

Turnover in bonds is much higher, and the market value weightings mean that the indices own a lot of the most indebted firms.

- And indeed, active bond funds have outperformed their benchmarks (after fees) from 1997 to 2017.

Unfortunately, that’s because they held more junk bonds (took higher risk).

- And junk bond returns are more highly correlated with those from stocks than are investment grade bond returns.

So it remains the case that the universe of passive funds will outperform the universe of active funds.

- Which is not to say that as a DIY investor, you can’t beat both.

Twitter pics

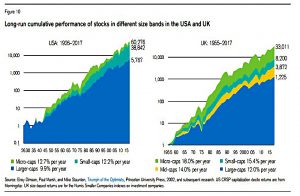

I have six for you this week.

- Let start with a couple from the Credit Suisse Yearbook.

This one shows the size effect, in the US and the UK.

- Smaller stocks do better.

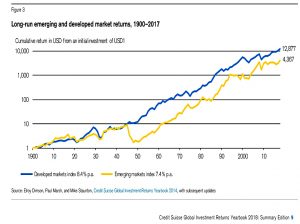

This one shows that developed markets have outperformed emerging markets in the long run, though the gap has closed since the 1980s.

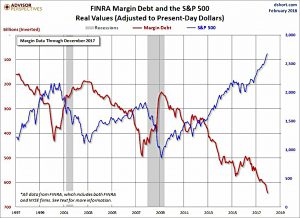

The next chart reminds us that margin debt goes up in a bull market.

The Monte die Paschi chart reminds us that stocks can go down a very long way and for a very long time.

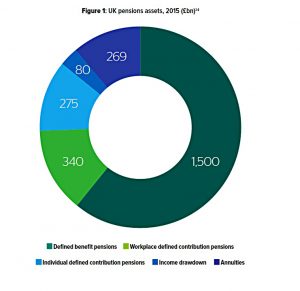

This chart reminds us of the continuing dominance of DB pensions in the UK landscape.

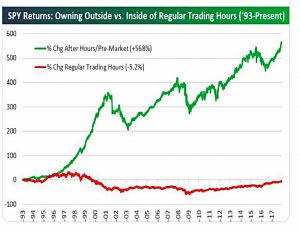

And the final chart for this week compares returns during market hours with those outside market hours (when the market is closed).

- This chart alone is enough to put me off intra-day trading.

It’s so much easier to make money while you sleep.

Until next time.

Once again here I am on the internet correcting the entirely inaccurate ( but often made in the media) statements about Continuing NHS Funded Care (CHC) vs local authority funded care. It is not the case that you can get CHC funding for a stroke or cancer but not for dementia. The eligibility is based on 1) complexity and 2) unpredictability of care needs. The threshold in all cases is very high and not surprisingly people cannot accept that their relative does not qualify when they see them bed bound and requiring round the clock care but deemed to have “only” social care needs.

Someone with dementia most certainly can qualify for CHC, but it requires them to have a very high level of needs, usually including very difficult challenging behaviour or other comorbidities making their care needs complex and unpredictable. Hence fewer people with dementia qualify, but the basic premise remains.

Equally most people having had strokes will not qualify for CHC. It is very unfortunate that the explanation is sometimes given by professionals that you qualify for CHC if you have “medical needs” but not “social” needs. This is misleading.

Lastly you can qualify for CHC funding on an entirely different basis, i.e. that you have a terminal illness with a very short life expectancy. Again this is easier to predict in say cancer than in end stage dementia. In that case you can qualify under the unfortunately named “fast track” conditions, nothing to do with complexity or unpredictability of need.

It may all seem very subjective and unfair and indeed it is. I frequently get furious replies to posts on this subject. Please note I am not approving the system, simply explaining it as most journalists totally fail to grasp the detail.

Hi Yvonne,

You win the (imaginary) prize for longest comment on my blog.

I have relied on the FT, I admit, but I wouldn’t say that CHC is the core point of the article.

Funding is not fair, that’s my point. I doubt that it’s possible for things to be fair.

Once we start paying for third parties, we start to have opinions about who those third parties should be, and how they should have lived to date.

Life is terribly subjective, I’m afraid.

I do think that it’s unfair for cancer to be socialised and dementia to be privatised.

Best,

Mike

Sorry for the long post. I tried to be concise but the fact is this subject is complicated. And as I said it’s not actually the case that cancer is socialised and dementia is privatised. Acute treatment is socialised but there’s virtually none for dementia. The social/medical division is highly subjective not helped by the fact that the NHS has drawn it’s criteria ever tighter… but there I go again. The FT article was helpful btw but even that had factual inaccuracy – the first 13 weeks of resi care are not free but subject to assessed contribution.

Yvonne – I think you may be closer to the coal face than I am. In which case you have my sympathies.

I think the current system is rewarding bad people and penalising good people. I can’t make it any simpler than that.

I’d like to start again from scratch. I’m paying for a lot of people that I don’t want to.

People should take responsibility for themselves and stop looking for help.

Mike